Towards Phosphorus Free Ionic Liquid Anti-Wear Lubricant Additives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Miscibility

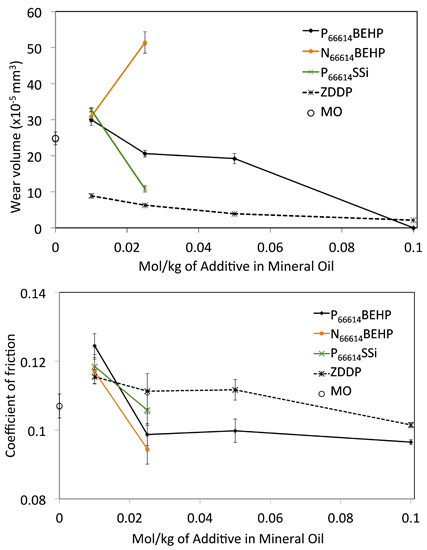

2.2. Wear Testing

2.3. Surface Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Additives

3.2. Synthesis Procedure

3.2.1. (N8,8,8,8)(BEHP)

3.2.2. (N6,6,6,14)(BEHP)

3.3. Viscosity, Conductivity and Wear Testing Methodologies

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmberg, K.; Andersson, P.; Nylund, N.-O.; Mäkelä, K.; Erdemir, A. Global energy consumption due to friction in trucks and buses. Tribol. Int. 2014, 78, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spikes, H. The history and mechanisms of ZDDP. Tribol. Lett. 2004, 17, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, M.A.; Do, T.; Norton, P.R.; Kasrai, M.; Bancroft, G.M. Review of the lubrication of metallic surfaces by zinc dialkyl-dithiophosphates. Tribol. Int. 2005, 38, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L. Room-temperature ionic liquids: A novel versatile lubricant. Chem. Commun. 2001, 2244–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.D.; Jiménez, A.E.; Sanes, J.; Carrión, F.J. Ionic liquids as advanced lubricant fluids. Molecules 2009, 14, 2888–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, A.; Howlett, P.; MacFarlane, D.; Forsyth, M. A Review of Ionic Liquid Lubricants. Lubricants 2013, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, I. Ionic liquids in tribology. Molecules 2009, 14, 2286–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Liang, Y.; Liu, W. Ionic liquid lubricants: Designed chemistry for engineering applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, A.E.; Khemchandani, B.; Howlett, P.C.; Sun, J.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Forsyth, M. Ionic Liquids as Antiwear Additives in Base Oils: Influence of Structure on Miscibility and Antiwear Performance for Steel on Aluminum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 11544–11553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, R.; Bartolomé, M.; Blanco, D.; Viesca, J.L.; Fernández-González, A.; Battez, A.H. Effectiveness of phosphonium cation-based ionic liquids as lubricant additive. Tribol. Int. 2016, 98, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Bansal, D.G.; Yu, B.; Howe, J.Y.; Luo, H.; Dai, S.; Li, H.; Blau, P.J.; Bunting, B.G.; Mordukhovich, G.; et al. Antiwear performance and mechanism of an oil-miscible ionic liquid as a lubricant additive. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Bansal, D.G.; Qu, J.; Sun, X.; Luo, H.; Dai, S.; Blau, P.J.; Bunting, B.G.; Mordukhovich, G.; Smolenski, D.J. Oil-miscible and non-corrosive phosphonium-based ionic liquids as candidate lubricant additives. Wear 2012, 289, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dyck, J.; Graham, T.W.; Luo, H.; Leonard, D.N.; Qu, J. Ionic liquids composed of phosphonium cations and organophosphate, carboxylate, and sulfonate anions as lubricant antiwear additives. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13301–13311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnhill, W.C.; Qu, J.; Luo, H.; Meyer, H.M.; Ma, C.; Chi, M.; Papke, B.L. Phosphonium-Organophosphate Ionic Liquids as Lubricant Additives: Effects of Cation Structure on Physicochemical and Tribological Characteristics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22585–22593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerholt, A.; Weschta, M.; Bösmann, A.; Tremmel, S.; Korth, Y.; Wolf, M.; Schlücker, E.; Wehrum, N.; Lennert, A.; Uerdingen, M.; et al. Halide-Free Synthesis and Tribological Performance of Oil-Miscible Ammonium and Phosphonium-Based Ionic Liquids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurín, N.; Minami, I.; Sanes, J.; Bermúdez, M.D. Study of the effect of tribo-materials and surface finish on the lubricant performance of new halogen-free room temperature ionic liquids. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 366, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarbath-Evers, L.K.; Hunt, P.A.; Kirchner, B.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Zahn, S. Molecular features contributing to the lower viscosity of phosphonium ionic liquids compared to their ammonium analogues. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 20205–20216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Truhan, J.; Dai, S.; Luo, H.; Blau, P. Ionic liquids with ammonium cations as lubricants or additives. Tribol. Lett. 2006, 22, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Howlett, P.C.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Lin, J.; Forsyth, M. Synthesis and physical property characterisation of phosphonium ionic liquids based on P(O)2(OR)2− and P(O)2(R)2− anions with potential application for corrosion mitigation of magnesium alloys. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 54, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Luo, H. Corrosion Prevention of Magnesium Surfaces via Surface Conversion Treatments Using Ionic Liquids. U.S. Patent 14/044,248, 2 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hamrock, B.J. Fundamentals of Fluid Film Lubrication, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994; p. 690. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.A.; Higgs Iii, C.F.; Lovell, M.R. A pin-on-disk experimental study on a green particulate-fluid lubricant. J. Tribol. 2008, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, H. The determination of the pressure-viscosity coefficient of a lubricant through an accurate film thickness formula and accurate film thickness measurements. J. Eng. Tribol. 2009, 223, 1143–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensado, A.S.; Comuñas, M.J.P.; Fernández, J. The pressure-viscosity coefficient of several ionic liquids. Tribol. Lett. 2008, 31, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, G.; Mourhatch, R.; Aswath, P.B. Effect of contact load and lubricant volume on the properties of tribofilms formed under boundary lubrication in a fully formulated oil under extreme load conditions. Wear 2010, 268, 1129–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ionic Liquid | Miscibility (mol·kg−1) | Conductivity (μs·cm−1) | Friction (Neat IL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (P6,6,6,14)(BEHP) | >0.10 | 2.1 | 0.096 |

| (N6,6,6,14)(BEHP) | 0.025 * | 0.8 | 0.090 |

| (N8,8,8,8)(BEHP) | Immiscible | 0.5 | 0.087 |

| (P6,6,6,14)(SSi) | 0.025 * | 5.9 | 0.089 |

| Additive | Viscosity (mPa·s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Neat | 0.025 mol·kg−1 | |

| (P6,6,6,14)(BEHP) | 405 | 19 |

| (N6,6,6,14)(BEHP) | 545 | 18 |

| (P6,6,6,14)(SSi) | 451 | 19 |

| ZDDP | – | 18 |

| mineral oil neat | 18 | – |

| Technique | (N8,8,8,8)(BEHP) | (N6,6,6,14)(BEHP) |

|---|---|---|

| 1H-NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) (500 MHz) CDCl3 | 0.78–0.85 (m, 24H, CH3, 3JH-H = 7 Hz) | 0.83–0.86 (m, 24H, CH3, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) |

| 1.28–1.53 (m, 58H, CH2, CH, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | 1.22–1.49 (m, 58H, CH2, CH, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | |

| 1.68 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | 1.63 (m, 8H, NCH2CH2, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | |

| 3.36 (dd, 8H, NCH2, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | 3.43 (dd, 8H, NCH2, 3JH-H = 8 Hz) | |

| 3.76 (m, 4H, OCH2, 3JH-H = 8 Hz, 3JH-P = 5.2 Hz) | 3.67 (m, 4H, OCH2, 3JH-H = 6.6 Hz, 3JH-P = 4.9 Hz) | |

| Electrospray ionization (m/z) | 466.4 (M+) and 321.1 (M−) | 466.5 (M+) and 321.2 (M−) |

| Elemental analysis | Anal. Calcd for C48H104.5NO5.25P: C, 71.10; H, 12.99; N, 1.72. | Anal. Calcd for C48H105NO5.5P: C, 70.7; H, 12.98; N, 1.71. |

| Found: C, 71.04; H, 13.08; N, 1.66 | Found: C, 70.66; H, 13.1; N, 1.62 | |

| Bromide | 0.1% | 0.01% |

| Element | wt% |

|---|---|

| C | 0.98–1.10 |

| Si | 0.15–0.3 |

| Mn | 0.25–0.45 |

| Cr | 1.3–1.6 |

| S | 0.025 max |

| P | 0.025 max |

| Others | – |

| Fe | Balance |

| Hardness (Vickers) | 850 |

| Ra (µm) | 0.05 (ball) 0.03 (disk) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Somers, A.E.; Yunis, R.; Armand, M.B.; Pringle, J.M.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Forsyth, M. Towards Phosphorus Free Ionic Liquid Anti-Wear Lubricant Additives. Lubricants 2016, 4, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants4020022

Somers AE, Yunis R, Armand MB, Pringle JM, MacFarlane DR, Forsyth M. Towards Phosphorus Free Ionic Liquid Anti-Wear Lubricant Additives. Lubricants. 2016; 4(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants4020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSomers, Anthony E., Ruhamah Yunis, Michel B. Armand, Jennifer M. Pringle, Douglas R. MacFarlane, and Maria Forsyth. 2016. "Towards Phosphorus Free Ionic Liquid Anti-Wear Lubricant Additives" Lubricants 4, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants4020022