-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Terrence E. Murphy, Dorothy I. Baker, Linda S. Leo-Summers, Luann Bianco, Margaret Gottschalk, Denise Acampora, Mary B. King, Integration of Fall Prevention into State Policy in Connecticut, The Gerontologist, Volume 53, Issue 3, June 2013, Pages 508–515, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns122

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Purpose of Study: To describe the ongoing efforts of the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention (CCFP) to move evidence regarding fall prevention into clinical practice and state policy. Methods: A university-based team developed methods of networking with existing statewide organizations to influence clinical practice and state policy. Results: We describe steps taken that led to funding and legislation of fall prevention efforts in the state of Connecticut. We summarize CCFP’s direct outreach by tabulating the educational sessions delivered and the numbers and types of clinical care providers that were trained. Community organizations that had sustained clinical practices incorporating evidence-based fall prevention were subsequently funded through mini-grants to develop innovative interventional activities. These mini-grants targeted specific subpopulations of older persons at high risk for falls. Implications: Building collaborative relationships with existing stakeholders and care providers throughout the state, CCFP continues to facilitate the integration of evidence-based fall prevention into clinical practice and state-funded policy using strategies that may be useful to others.

Fall-related injuries are one of the most common, disruptive, and costly health conditions experienced by older adults in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Although randomized controlled trials support the efficacy of multicomponent fall-prevention strategies in reducing these risks (American Geriatrics Society, 2010; Tinetti et al., 1994), effective strategies to prevent falls are underutilized.

As has been described in detail elsewhere, the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention (CCFP) is an ongoing 12-year effort designed to move evidence regarding prevention of falls among older persons into use by the variety of clinicians and practice settings where older adults receive health care (Baker et al., 2005; Chou, Tinetti, King, Irwin, & Fortinsky, 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2004). To accomplish this, research protocols were converted into clinical assessment guidelines and patient education materials by workgroups of clinicians from a variety of settings including outpatient rehabilitation, home care, emergency room, and the offices of primary care physicians. Using these materials, a multidisciplinary cadre of CCFP investigators actively recruited clinical sites throughout an intervention region and provided them with materials and in-service educational sessions. A database was developed to register individual participants and to send a monthly newsletter providing updates regarding CCFP and current research in fall prevention.

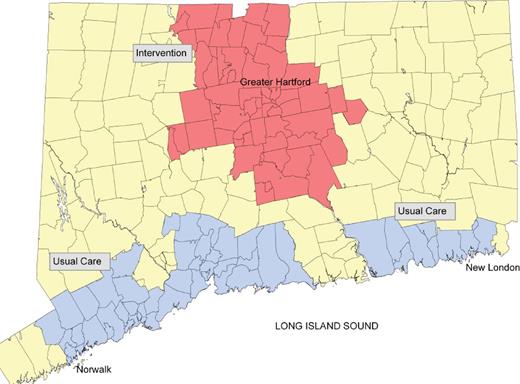

The evaluation plan assessed the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing the number of older adults admitted for emergency or hospital care for fall-related injury in the intervention region relative to a usual-care area selected to be similar at an aggregate level on key fall-related factors (Murphy, Tinetti, & Allore, 2008; Murphy, Allore, Leo-Summers, & Carlin, 2011; Tinetti et al., 2008). Over a two-year evaluation period, the intervention area experienced a 9% decline in the rate of serious fall-related injury admissions relative to that of the usual-care area. Over the same period, a decline of 11% in the adjusted rate of overall fall-related use of medical services in the intervention area with respect to the usual-care area was also documented. The evaluations of serious and overall fall-related injury each employed Bayesian Poisson models that adjusted for spatial correlation, age, sex, time period within the study, and the following zip-code specific covariates: baseline rate of fall-related injury, proportion of 65+ households with income ≤ $15,000, proportion of 65+ households with income ≥ $75,000, proportion of 65+ persons living in institutions, proportion of 65+ noninstitutionalized persons with physical disability, and the proportion of 65+ persons with self-reported race that was non-White. The intervention and usual-care areas are presented in Figure 1. For notational purposes, in this article we will refer to the initial research study as CCFP1, which took place over the years 2000 through 2006.

Usual care and intervention arms of the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 1 (2000–2006).

Informing State Policy and Securing Funding from State Legislature

Given that the intervention successfully reduced use of fall-related health care services, efforts were undertaken to inform state policymakers. To develop an understanding of how to accomplish this, CCFP researchers were given invaluable assistance by groups experienced in political advocacy for older adults in Connecticut. These included the Long-Term Care Planning Committee, The Commission on Aging, and the Association of Area Agencies on Aging, among others. Fortunately, the State Department of Public Health developed graphic data tables illustrating falls as Connecticut’s most common and costly injury. With guidance from these groups, it became apparent that in addition to demonstrating that we could reduce the rate of falls, it would be essential to estimate the financial costs and potential savings that the state of Connecticut might achieve if the intervention was to be implemented statewide. To accomplish this, state and federal falls data were used to estimate the number of older adults in Connecticut that sustain fall-related injuries each year, and the proportion thereof that subsequently need state supported long-term community or nursing home care via nursing home alternative programming and/or the Medicaid program. When estimates of the financial impact had been reviewed by state officials who were knowledgeable about the state costs of long-term care, a CCFP investigator began meeting to inform individuals in state government and legislators from key committees about the magnitude of the problem, costs, and the potential for savings.

A key legislator agreed to sponsor a bill that would integrate fall-prevention efforts into state policy. Draft bill language was provided to her, and after editing and review, it was introduced and passed by both the house and senate, but ultimately left unsigned by the Governor. In spite of failing to pass the bill, individual meetings and public testimony to influential state committees and legislators resulted in the 2007 state budget funding fall prevention. Funds were appropriated to the Aging Services Division in the Department of Social Services who contracted with the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention based at Yale University to undertake statewide dissemination. We refer to this first state-funded dissemination effort (2007–2009) as CCFP2.

In 2009 as the initial round of state funding was drawing to a close, the key legislators agreed to again sponsor a bill that would integrate fall-prevention efforts into state policy. A number of legislators cosponsored the bill that passed and provided, contingent on available funds, an outline of activities to be supported and appropriations for statewide fall-prevention efforts.

We will later refer to the second state-funded effort as CCFP3, which took place in the years 2010 and 2011. The timeline and objectives of these sequential projects are depicted in Table 1.

Phases of the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention

| Time . | 2000–2006 . | 2007–2009 . | 2010–2011 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | CCFP1 | CCFP2 | CCFP3 |

| Funding | Donaghue Foundation (Private source) | State of Connecticut | State of Connecticut |

| Aims | 1. Translate research findings into effective community intervention | 1. Disseminate intervention throughout remainder of state | 1. Continue general outreach |

| 2. Disseminate intervention throughout Greater Hartford | 2. Fund local innovations that further integrate fall prevention into care of older persons | ||

| 3. Evaluate effectiveness of intervention | |||

| Publications | Baker et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2004; Murphy, Tinetti, & Allore, 2008; Murphy, Allore, Leo-Summers, & Carlin, 2011; Tinetti et al., 2008 |

| Time . | 2000–2006 . | 2007–2009 . | 2010–2011 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | CCFP1 | CCFP2 | CCFP3 |

| Funding | Donaghue Foundation (Private source) | State of Connecticut | State of Connecticut |

| Aims | 1. Translate research findings into effective community intervention | 1. Disseminate intervention throughout remainder of state | 1. Continue general outreach |

| 2. Disseminate intervention throughout Greater Hartford | 2. Fund local innovations that further integrate fall prevention into care of older persons | ||

| 3. Evaluate effectiveness of intervention | |||

| Publications | Baker et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2004; Murphy, Tinetti, & Allore, 2008; Murphy, Allore, Leo-Summers, & Carlin, 2011; Tinetti et al., 2008 |

Phases of the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention

| Time . | 2000–2006 . | 2007–2009 . | 2010–2011 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | CCFP1 | CCFP2 | CCFP3 |

| Funding | Donaghue Foundation (Private source) | State of Connecticut | State of Connecticut |

| Aims | 1. Translate research findings into effective community intervention | 1. Disseminate intervention throughout remainder of state | 1. Continue general outreach |

| 2. Disseminate intervention throughout Greater Hartford | 2. Fund local innovations that further integrate fall prevention into care of older persons | ||

| 3. Evaluate effectiveness of intervention | |||

| Publications | Baker et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2004; Murphy, Tinetti, & Allore, 2008; Murphy, Allore, Leo-Summers, & Carlin, 2011; Tinetti et al., 2008 |

| Time . | 2000–2006 . | 2007–2009 . | 2010–2011 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | CCFP1 | CCFP2 | CCFP3 |

| Funding | Donaghue Foundation (Private source) | State of Connecticut | State of Connecticut |

| Aims | 1. Translate research findings into effective community intervention | 1. Disseminate intervention throughout remainder of state | 1. Continue general outreach |

| 2. Disseminate intervention throughout Greater Hartford | 2. Fund local innovations that further integrate fall prevention into care of older persons | ||

| 3. Evaluate effectiveness of intervention | |||

| Publications | Baker et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2006; Fortinsky et al., 2004; Murphy, Tinetti, & Allore, 2008; Murphy, Allore, Leo-Summers, & Carlin, 2011; Tinetti et al., 2008 |

The First State-Sponsored Dissemination of Fall Prevention in Connecticut (CCFP2)

The Greater Hartford area had been saturated with fall prevention activity during the dissemination phase of CCFP1. The initial round of state funding, CCFP2, focused on reaching the remainder of the state. This effort was designed with the goal of engaging agencies concerned with older persons in the state of Connecticut whose organizational mission statement held a potential role for evidence-based fall prevention. State databases were used to develop comprehensive lists of candidate organizations. Individual meetings with the chief executive officers of key organizations were arranged to describe the magnitude of the problem in the state and how fall prevention might be integrated into the mission of the index organization. Clinical supervisors subsequently assembled clinical staff for in-service education programs. Attendees were asked to register in the CCFP database, which provided (a) descriptive data of attendees, (b) contact information used to send a monthly e-mail newsletter to keep them apprised of ongoing efforts in the state, and new fall-prevention research publications. In addition to directly reaching 4000 clinicians, these newsletters were often reproduced within their respective organizations and further circulated in organizational notices. Table 2 lists the type and number of facilities where training took place and the number of clinicians directly trained.

Facilities Hosting Training and Corresponding Numbers of Clinicians Trained in Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention from 2007 to 2009

| Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 2: Participation by facility type, count, and number of attendees . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Facility type . | Number of facilities . | Number of Individual clinicians . |

| Home care | 68 | 227 |

| Senior center | 26 | 27 |

| Health Dept./Social services | 24 | 50 |

| Hospital Affiliated Outpatient Rehab | 26 | 78 |

| Freestanding Outpatient Rehab | 25 | 32 |

| Subacute facilities | 29 | 53 |

| Hospital | 32 | 417 |

| State Medical Society/Organization | 10 | 261 |

| University | 8 | 23 |

| Other facility | 8 | 8 |

| Community wellness/health fairs | 7 | 200 |

| Area Agency on Aging | 4 | 38 |

| Assisted living | 34 | 58 |

| Health network | 5 | 7 |

| Senior housing | 5 | 5 |

| Church/Religious centers | 3 | 20 |

| Home health care (nonmedical) | 5 | 15 |

| Adult day care | 3 | 6 |

| Total estimated reach | 322 | 1525 |

| Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 2: Participation by facility type, count, and number of attendees . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Facility type . | Number of facilities . | Number of Individual clinicians . |

| Home care | 68 | 227 |

| Senior center | 26 | 27 |

| Health Dept./Social services | 24 | 50 |

| Hospital Affiliated Outpatient Rehab | 26 | 78 |

| Freestanding Outpatient Rehab | 25 | 32 |

| Subacute facilities | 29 | 53 |

| Hospital | 32 | 417 |

| State Medical Society/Organization | 10 | 261 |

| University | 8 | 23 |

| Other facility | 8 | 8 |

| Community wellness/health fairs | 7 | 200 |

| Area Agency on Aging | 4 | 38 |

| Assisted living | 34 | 58 |

| Health network | 5 | 7 |

| Senior housing | 5 | 5 |

| Church/Religious centers | 3 | 20 |

| Home health care (nonmedical) | 5 | 15 |

| Adult day care | 3 | 6 |

| Total estimated reach | 322 | 1525 |

Facilities Hosting Training and Corresponding Numbers of Clinicians Trained in Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention from 2007 to 2009

| Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 2: Participation by facility type, count, and number of attendees . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Facility type . | Number of facilities . | Number of Individual clinicians . |

| Home care | 68 | 227 |

| Senior center | 26 | 27 |

| Health Dept./Social services | 24 | 50 |

| Hospital Affiliated Outpatient Rehab | 26 | 78 |

| Freestanding Outpatient Rehab | 25 | 32 |

| Subacute facilities | 29 | 53 |

| Hospital | 32 | 417 |

| State Medical Society/Organization | 10 | 261 |

| University | 8 | 23 |

| Other facility | 8 | 8 |

| Community wellness/health fairs | 7 | 200 |

| Area Agency on Aging | 4 | 38 |

| Assisted living | 34 | 58 |

| Health network | 5 | 7 |

| Senior housing | 5 | 5 |

| Church/Religious centers | 3 | 20 |

| Home health care (nonmedical) | 5 | 15 |

| Adult day care | 3 | 6 |

| Total estimated reach | 322 | 1525 |

| Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 2: Participation by facility type, count, and number of attendees . | ||

|---|---|---|

| Facility type . | Number of facilities . | Number of Individual clinicians . |

| Home care | 68 | 227 |

| Senior center | 26 | 27 |

| Health Dept./Social services | 24 | 50 |

| Hospital Affiliated Outpatient Rehab | 26 | 78 |

| Freestanding Outpatient Rehab | 25 | 32 |

| Subacute facilities | 29 | 53 |

| Hospital | 32 | 417 |

| State Medical Society/Organization | 10 | 261 |

| University | 8 | 23 |

| Other facility | 8 | 8 |

| Community wellness/health fairs | 7 | 200 |

| Area Agency on Aging | 4 | 38 |

| Assisted living | 34 | 58 |

| Health network | 5 | 7 |

| Senior housing | 5 | 5 |

| Church/Religious centers | 3 | 20 |

| Home health care (nonmedical) | 5 | 15 |

| Adult day care | 3 | 6 |

| Total estimated reach | 322 | 1525 |

To encourage participation, the training sessions were approved to provide continuing education credit hours for the physical therapists, occupational therapists (OT), and nurses. An online fall-prevention course for physicians was also developed that awarded continuing medical education (CME) credits. The regulatory division of the Department of Public Health was contacted and approved fall-prevention coursework for meeting the CME requirement for physician state licensure regarding patient safety/risk management.

A particularly effective and efficient strategy for reaching a broad spectrum of providers within a geographical region was having hospitals host training sessions. In addition to receiving clinical training regarding risk assessment and intervention, CCFP brochures and framed posters of fall-prevention themes were provided to attendees. In the ideal case, these sessions started with a CCFP physician investigator who presented medical grand rounds to the physician community. In all instances, the CCFP nurse and physical therapy investigators conducted training for frontline clinicians from across the spectrum of health care facilities, including acute care, hospital-based and freestanding outpatient clinics, home care agencies, senior centers, public health departments, and subacute facilities. To foster development of local fall-prevention coalitions, all attending organizations were introduced and time was provided for attendees to network.

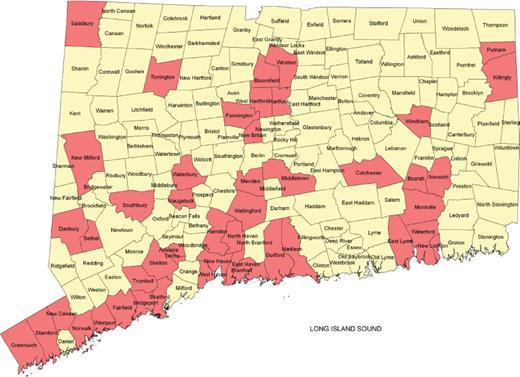

In addition to the teaching of clinical assessment and intervention, a second program was offered to train clinicians interested in teaching fall prevention to groups of older adults. These “train-the-trainer” sessions prepared a statewide network of clinicians willing and able to provide fall-prevention talks to groups of older adults at the request of local groups such as churches, senior centers, Parish Nurses, low-vision groups, and assisted living facilities. Trained clinicians initially received speaking requests via CCFP but quickly became locally known and were thereafter contacted directly by organizations in their communities. A total of 132 clinicians were trained to conduct group sessions: 56 physical therapists; three advanced practice registered nurses; 44 registered nurses; nine health educator/exercise instructors; five occupational therapists; five social worker/care managers; and one each of physician, pharmacist, and physical therapist aide. The geographical distribution of these training sessions is displayed in Figure 2, which shades in each town where at least one “train-the-trainer” session was held.

Connecticut towns where train-the-trainer sessions took place for Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 2 from 2007–2009.

The Second State-Sponsored Dissemination of Fall Prevention in Connecticut (CCFP3)

State funding for CCFP2 officially ended in June 2009. However, because patient safety was emerging as a priority to third-party funders and accrediting organizations, community providers continued many of their fall-prevention efforts. After an 8-month hiatus, state funding resumed in March 2010; however, the interruption in support fostered the conclusion that efforts should be devoted to cultivating local, sustainable resources independent of CCFP staff and training activities. To accomplish this, an effort was made to identify clinical agencies with a demonstrated commitment to implementing the basic multifactorial approach of fall prevention and then solicit proposals from them for expanding their clinical interventions and to specifically target their subpopulations of older persons at high risk for fall-related injury.

The 2010 American Geriatric Society/British Geriatric Society (AGS/BGS) Guidelines for the Prevention of Falls and state legislation provided a framework for these proposals (American Geriatrics Society, 2010). CCFP ultimately provided funding to eight regional organizations selected for their adherence to criteria emphasized in the AGS/BGS Guidelines and their capacity to expand. Funding provided the opportunity for clinicians to look beyond their day-to-day work and focus on the larger care system by developing new collaborations with other disciplines and settings. These networks catalyze a level of care that is impossible when each agency functions independently and are essential if multifactorial geriatric syndromes, including falls, are to be successfully addressed. The types of institution and specific content of their interventions are summarized in Table 3.

Description of Projects Funded by the State of Connecticut in 2010–2011

| Type of organization . | Innovative practices . |

|---|---|

| Hospitals | • Moving fall prevention into community outreach via hospital sponsored wellness programs, teaming outpatient rehabilitation therapists with pharmacists to assess individuals and intervene regarding safer use of medications and potential loss of mobility.• A hospital-based geriatric assessment clinical APRN and RN team to conduct home-based assessments of at risk older adults with follow-up to reinforce interventions. |

| Visiting Nurse Associations | • Active outreach to identify those who had fallen, followed by RN home visits to conduct assessments, and directly intervene with follow-up by rehabilitation therapists and primary care providers.• VNA Collaboration with a University School of Pharmacy: Fall prevention assessments conducted in the context of homecare were expanded to include polypharmacy review by supervised pharmacy students. The visiting nurse communicated the clinical picture with pharmacologic suggestions to the primary care provider, often resulting in medication changes.• Polypharmacy review was conducted by a VNA affiliated with a hospital network, thereby providing access to pharmacists to review medications and suggest safer regimens.• Group clinics were offered wherein older adults were led through self-assessment of their risks, augmented by individual nursing and one-on-one therapy assessments. Each person received instructions and further intervention and referral as needed. |

| Academic Department of Emergency Medicine | • Academic clinicians in emergency medicine and geriatrics collaborated to develop, test, and evaluate the efficacy of fall risk assessment protocols used to evaluate patients who dialed 9-1-1 for a “lift assist” defined as requesting help moving from an undesired position, but not wanting transport.• These lift assist calls were determined to be frequent, costly, and often meant repeated 9-1-1 calls within 30 days. A lift assist is now recognized as an opportunity to intervene earlier. |

| Type of organization . | Innovative practices . |

|---|---|

| Hospitals | • Moving fall prevention into community outreach via hospital sponsored wellness programs, teaming outpatient rehabilitation therapists with pharmacists to assess individuals and intervene regarding safer use of medications and potential loss of mobility.• A hospital-based geriatric assessment clinical APRN and RN team to conduct home-based assessments of at risk older adults with follow-up to reinforce interventions. |

| Visiting Nurse Associations | • Active outreach to identify those who had fallen, followed by RN home visits to conduct assessments, and directly intervene with follow-up by rehabilitation therapists and primary care providers.• VNA Collaboration with a University School of Pharmacy: Fall prevention assessments conducted in the context of homecare were expanded to include polypharmacy review by supervised pharmacy students. The visiting nurse communicated the clinical picture with pharmacologic suggestions to the primary care provider, often resulting in medication changes.• Polypharmacy review was conducted by a VNA affiliated with a hospital network, thereby providing access to pharmacists to review medications and suggest safer regimens.• Group clinics were offered wherein older adults were led through self-assessment of their risks, augmented by individual nursing and one-on-one therapy assessments. Each person received instructions and further intervention and referral as needed. |

| Academic Department of Emergency Medicine | • Academic clinicians in emergency medicine and geriatrics collaborated to develop, test, and evaluate the efficacy of fall risk assessment protocols used to evaluate patients who dialed 9-1-1 for a “lift assist” defined as requesting help moving from an undesired position, but not wanting transport.• These lift assist calls were determined to be frequent, costly, and often meant repeated 9-1-1 calls within 30 days. A lift assist is now recognized as an opportunity to intervene earlier. |

Note. APRN = advanced practice registered nurse; RN = registered nurse; VNA = visiting nurse association.

Description of Projects Funded by the State of Connecticut in 2010–2011

| Type of organization . | Innovative practices . |

|---|---|

| Hospitals | • Moving fall prevention into community outreach via hospital sponsored wellness programs, teaming outpatient rehabilitation therapists with pharmacists to assess individuals and intervene regarding safer use of medications and potential loss of mobility.• A hospital-based geriatric assessment clinical APRN and RN team to conduct home-based assessments of at risk older adults with follow-up to reinforce interventions. |

| Visiting Nurse Associations | • Active outreach to identify those who had fallen, followed by RN home visits to conduct assessments, and directly intervene with follow-up by rehabilitation therapists and primary care providers.• VNA Collaboration with a University School of Pharmacy: Fall prevention assessments conducted in the context of homecare were expanded to include polypharmacy review by supervised pharmacy students. The visiting nurse communicated the clinical picture with pharmacologic suggestions to the primary care provider, often resulting in medication changes.• Polypharmacy review was conducted by a VNA affiliated with a hospital network, thereby providing access to pharmacists to review medications and suggest safer regimens.• Group clinics were offered wherein older adults were led through self-assessment of their risks, augmented by individual nursing and one-on-one therapy assessments. Each person received instructions and further intervention and referral as needed. |

| Academic Department of Emergency Medicine | • Academic clinicians in emergency medicine and geriatrics collaborated to develop, test, and evaluate the efficacy of fall risk assessment protocols used to evaluate patients who dialed 9-1-1 for a “lift assist” defined as requesting help moving from an undesired position, but not wanting transport.• These lift assist calls were determined to be frequent, costly, and often meant repeated 9-1-1 calls within 30 days. A lift assist is now recognized as an opportunity to intervene earlier. |

| Type of organization . | Innovative practices . |

|---|---|

| Hospitals | • Moving fall prevention into community outreach via hospital sponsored wellness programs, teaming outpatient rehabilitation therapists with pharmacists to assess individuals and intervene regarding safer use of medications and potential loss of mobility.• A hospital-based geriatric assessment clinical APRN and RN team to conduct home-based assessments of at risk older adults with follow-up to reinforce interventions. |

| Visiting Nurse Associations | • Active outreach to identify those who had fallen, followed by RN home visits to conduct assessments, and directly intervene with follow-up by rehabilitation therapists and primary care providers.• VNA Collaboration with a University School of Pharmacy: Fall prevention assessments conducted in the context of homecare were expanded to include polypharmacy review by supervised pharmacy students. The visiting nurse communicated the clinical picture with pharmacologic suggestions to the primary care provider, often resulting in medication changes.• Polypharmacy review was conducted by a VNA affiliated with a hospital network, thereby providing access to pharmacists to review medications and suggest safer regimens.• Group clinics were offered wherein older adults were led through self-assessment of their risks, augmented by individual nursing and one-on-one therapy assessments. Each person received instructions and further intervention and referral as needed. |

| Academic Department of Emergency Medicine | • Academic clinicians in emergency medicine and geriatrics collaborated to develop, test, and evaluate the efficacy of fall risk assessment protocols used to evaluate patients who dialed 9-1-1 for a “lift assist” defined as requesting help moving from an undesired position, but not wanting transport.• These lift assist calls were determined to be frequent, costly, and often meant repeated 9-1-1 calls within 30 days. A lift assist is now recognized as an opportunity to intervene earlier. |

Note. APRN = advanced practice registered nurse; RN = registered nurse; VNA = visiting nurse association.

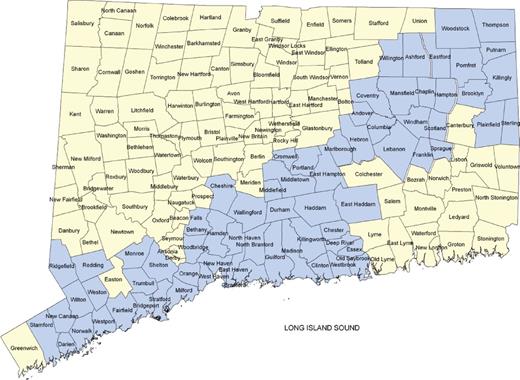

The shaded regions of the map presented in Figure 3 depict the coverage provided to various parts of the state of Connecticut by the regional endeavors promoted in CCFP3 between March 2010 and June 2011.

Overall coverage area of the state-sponsored regional projects for Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention 3 in 2010–2011.

Discussion

Because our efforts culminated in state funding that has now spanned 5 years and official state policy that encourages fall prevention, the following outline of the process may be of use to others interested in implementing similar activities.

Stages: Integrating fall prevention into state policy

Begin with private foundation funding to conduct regional dissemination research demonstrating effectiveness at the community level. Develop a statewide network of community service providers to older persons.

Solicit advice from leaders in the policy and political arena (e.g., in Connecticut, The Commission on Aging, Long-Term Planning Committee and Organization of Area Agencies on Aging) regarding their current priorities, the “fit” of fall prevention to organizational priorities and to issues currently under consideration at the policy level.

Participate in the legislative efforts of other groups that logically link to fall prevention, for example, efforts of the Brain Injury Association, and groups concerned with safer use of medication.

Identify departments within state government concerned with care of the aging population and related costs, where fall prevention would logically be implemented. Educate Commissioners and key directors of these departments regarding fall prevention.

Based on the advice and counsel noted previously, develop brief, consistent, easily communicated messages to link fall prevention with the mission of key state departments, legislative committees, current legislative issues, and the Governor’s budget office.

Draw on the statewide network of relevant clinical agencies to write letters, provide testimony at bill hearings, and personally contact elected legislators.

Identify key legislators who support the effort and are willing to introduce and cosponsor legislation.

Meet with key committee members and subsequently testify before the appropriations committee and related budget committees to gain support from those responsible for funding.

Limitations: It is our intent to describe a sequence of events in one state to assist those who wish to embark on similar efforts in different regions of the country. We note that the total CCFP dissemination effort has taken 12 years, to date. Below is a list of particular geographical and temporal circumstances that may limit the generalizability of our approach in other regions. These limitations include but are not restricted to the following:

Falling is unique among health conditions in that virtually everyone, including state legislators and the Governor of Connecticut, know of or have experienced a fall-related injury or death. Despite this fact, the magnitude of the problem has only recently become a recognized and pressing public concern.

State legislators were receptive to our efforts in part because the original research was conducted among their constituents, that is, the results were not “imported” from another part of the country.

The results of our original research were timely in that the costs of long-term care were taking on increasing urgency in the state precisely when statewide dissemination and potential cost effectiveness were being proposed.

We cannot gauge the extent to which our state differs from others with respect to having a respected group of politically savvy advocates for older adults. However, it was clearly our experience that moving this evidence into policy would have been impossible without the selfless assistance provided by the seasoned political veterans who agreed to help us in the interest of providing optimal services to the older adults of our state.

Conclusion

As evidenced by the 2011 National Council on Aging’s national map showing the existence of fall-prevention coalitions (National Council on Aging) in the majority of the country there currently is some level of state effort regarding fall prevention. Complemented by a growing number of methodological innovations (Blair & Minkler, 2009; Yamashita, Noe, & Bailer, 2012; Zecevic, Salmoni, Lewko, Vandervoort, & Speechley, 2009), this map reflects the growing national awareness of the importance of fall prevention among community-dwelling older persons. In this article, we have summarized the long sequence of dissemination events that followed the completion of the original randomized clinical trial (Tinetti et al., 1994). But the core content of the interventional protocol has not changed because that clinical trial, which defined specific clinical interventional practices, is only a first step in the dilatory process of changing public policy. Developing the links between evidence provided by randomized clinical trials, practical clinical protocols, and ultimately legislative priorities required extending and reformatting the message to address the purview of a variety of stakeholders. This refining and extension of the evidence-based fall-prevention message was of critical importance in moving clinical evidence into practice and policy.

As evidenced by the mini-projects of CCFP3, the reduction of multiple risk factors for fall-related injury can be approached from many angles by a wide variety of clinicians in different settings. In Connecticut, a collaboration of public and private organizations continues to discover and refine effective ways of helping health care providers practice fall prevention. Over time, the goal remains unchanged: to help older adults learn that they are at risk for fall-related injury and how to reduce their risks. These efforts benefit not only those at risk, but also those who care for them as well as those who pay for their health care.

Funding

Supported by a grant from the Aging Services Division of the State of Connecticut Department of Social Services to the Connecticut Collaboration for Fall Prevention (CCFP) at Yale University School of Medicine (PI-Baker) and by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (1R21AG033130-01A2, PI-Murphy). The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors. The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG21342). The original CCFP efforts were supported by the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (DF#00-206). This publication was made possible in part by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 (PI-Murphy) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical research. Its contents are solely the views and opinions of the authors and not those of the Connecticut Department of Social Services, the State of Connecticut, the NCRR or the NIH.

Acknowledgments

This project would not have been possible without the ongoing creative collaborative efforts of 4000+ clinicians across Connecticut and the policy guidance generously and patiently provided by Julie Evans-Starr. Data structuring is to the credit of John O’Leary and Peter Charpentier. We thank Mary Tinetti for her pioneering work and leadership in fall prevention.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Kimberly Van Haitsma, PhD