Abstract

Variation in wavelength sensitivity among subspecies is unknown among vertebrates. The parrot Platycercus elegans has extreme plumage variation between subspecies ranging from pale yellow to crimson which, with differences in background colour and light environment between subspecies, makes it a good candidate for the evolution of within-species differences in vision. We report differences in visual pigments between populations of P. elegans from two subspecies, providing the first known support for population and subspecies variation in visual pigments within a vertebrate species; it is also the first instance of intraspecific variation in rod sensitivity within any vertebrate species. Differences in wavelength sensitivity of rods and cones corresponded to geographic differences in plumage colour. Between study populations, visual pigments varied but not oil droplets. Adaptive functions for the visual pigment differences are untested but they could cause divergence in behaviours associated with colour as well as in dim light, and provide insights into the role of senses in divergence and speciation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rod and cone photoreceptors in the retina of the vertebrate eye are the fundamental basis for nocturnal and diurnal vision respectively, and the sensitivities of these photoreceptors have evolved to suit the visual needs of individuals in each species1. Vision within a species is thought to be broadly conserved between individuals and across populations within a species, including in birds2,3. However, most studies assessing adaptations in vision compare species, rather than separate populations within a species that occupy different niches4,5,6,7. Intraspecific variation in photoreceptor sensitivity is known from only a few vertebrate species, namely some teleost fish7,8,9 and primates (e.g. some New World monkeys10,11 and humans12,13). In these cases, intraspecific variation arises from within-population differences caused by differences between individuals in retinal photopigment alleles and/or their expression8,11,13. To date, intraspecific variation in vision has not been found between geographically separate populations of any species, nor within any bird species, nor in the rods of any vertebrate species.

The parrot Platycercus elegans (Gmelin 1788, Aves; Psittaciformes) shows extreme variation in plumage colouration between subspecies, ranging from deep crimson (in P. e. elegans) to pale yellow (in P. e. flaveolus)14. P. e. elegans occupies mesic wooded and forest habitats, and P. e. flaveolus more open riparian habitats14. Platycercus elegans is perhaps the most colour variable of the ca. 350 species of parrot worldwide and, based on the plumage variation, Cain15 considered the species an example of a circular overlapping or ‘ring’ species16,17, of which there are few worldwide. Recent studies of P. elegans focusing on population structure18, vocalisations19,20,21,22, olfaction23 and viral infection24, however, have revealed a more complex phylogeography than proposed in the simple ‘ideal’ ring species model proposed by Mayr17. Of particular interest are the selective pressures driving and maintaining the evolution of the plumage colour variation in P. elegans, many of which remain enigmatic25. Sensory drive theories26,27, in combination with predictions arising from the known differences in the subspecies’ light environments and background colouration1,27, make it is possible that consistent intraspecific differences in vision may have evolved in the different subspecies in P. elegans living in different habitats. Indeed, the molecular sequences of the retinal opsins of P. e. adelaidae, a subspecies with colouration intermediate to P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus reveal sequence extensions and splicing events previously unknown in any vertebrate28. Using the two most divergent subspecies of the complex (P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus) we compared their rods and all known cone types for spectral sensitivity differences; our approach allowed us to partition differences due to visual pigments, or the oil droplets that overlie visual pigments in birds.

Results

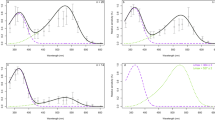

Microspectrophotometry (MSP) revealed all the expected parrot visual pigment types28,29,30 in both the P. e. elegans and the P. e. flaveolus populations (Table 1; Fig. 1). For the rod, longwave sensitive (LWS), and mediumwave sensitive (MWS) cone visual pigments, we found significant differences in the wavelength of maximum sensitivity (λmax) between the two study populations (Table 1; Fig. 2a,b,e), with those from the P. e. flaveolus population at consistently longer wavelengths than visual pigments from the P. e. elegans population (Table 1; Fig. 2a,b,e). There were non-significant differences between sub-species in λmax of the shortwave sensitive (SWS) and ultraviolet sensitive (UVS) cone visual pigments (Table 1; Fig. 2c,d). As expected from numerous terrestrial vertebrate studies, photoreceptors containing SWS and UVS visual pigments were infrequent. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.30, 0.55, and 0.75 for LWS, MWS and rod visual pigments respectively. These indicate that 30%, 55%, and 75% of variance was associated with differences between individuals for LWS, MWS, and rod visual pigments respectively. The ICCs were not calculated for SWS and UVS because there were too few repeated measurements across individuals. Data were normally distributed and homoscedastic. These ICC values are within the range reported for earlier MSP work on bird eyes, both in cone outer segments and in oil droplets31. Because we have sampled from a single population of each subspecies we cannot say whether this is a population or subspecies difference, but the large ICC indicate that the intraspecific differences are real.

Left column: Mean visual pigment λmax for P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus for each visual pigment type. Error bars represent ± 1 standard error. Significant results are indicated by a black line and asterisk. Right column: Spread of all individual photoreceptor cell λmax for each individual bird, grouped by subspecies: Individuals 1–7: P. e. elegans; Individuals 8–12: P. e. flaveolus. Rows: a: LWS; b: MWS; c: SWS; d: UVS; e: Rod.

MSP revealed all expected parrot retinal oil droplets types (Table 2). No significant differences in the cut-off wavelength (λcut)32 were found between the populations for any oil droplet types (Table 2). Predicted sensitivity curves for single cones, incorporating visual pigment sensitivity, oil droplet absorbance and cone ratios are shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion

We report the first case in a vertebrate of intraspecific differences in spectral sensitivity corresponding to population and geographic differences. These differences occurred in both cones and rods, and the rod difference is the first case of intraspecific variation in rods in any vertebrate. In the cones, the differences in spectral sensitivity were due to differences in visual pigments rather than oil droplets. Where there were significant differences in visual pigments (LWS, MWS, rods) the population exhibiting plumage dominated by longer wavelength reflectance (P. e. elegans) had visual pigments sensitive to shorter wavelengths. Consequently, our results offer the first evidence in a bird that intraspecific geographic variation in photoreceptor tuning relates to integument colouration, and provides the first example of intraspecific variation in avian colour vision.

We show that significant differences exist between P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus in the peak absorbance of the visual pigments contained in both rod, LWS and MWS cone photoreceptors. This confirms an a priori prediction that we tested earlier in budgerigar colour morphs31 in which we found no differences in oil droplets between colour morphs. However, the budgerigar colour morphs tested were produced by captive breeding and do not occur in the wild, where there is a single wild-type morph33. Here, using wild-caught individuals of a species, P. elegans, with naturally occurring extreme intraspecific plumage variation, we found consistent differences, and in several visual pigments. The selective advantages of these differences in P. elegans are not yet clear, but may relate to differences in habitat background coloration and light environment between P. elegans subspecies, combined with sensory drive theories34.

We did not find any differences between the two populations that we studied in the absorbance properties of oil droplet types (i.e. R-, Y-, C- and P-types). As in the great majority of bird species, and in our study reported here, the R-, Y-, C- and T-type oil droplets of single cones sit in the optical paths of the visual pigments LWS, MWS, SWS and VS/UVS, respectively. The T-type droplet has no detectable absorbance in birds, and the P-type droplet is found exclusively in the double cones2,35. Work on developing chicks36 found 6 weeks of manipulated ambient light was required for changes in oil droplet absorbance. Our previous research on adult P. elegans37 revealed that medium term (ca. 90 days) dietary manipulations of carotenoids and food availability did not affect oil droplets of single cones, and only affected the P-type droplets of double cones that apparently have no role on colour vision38,39. In the work reported here on adult P. elegans, the time birds were held in captivity prior to MSP was around 25 days. Consequently, there is no reason to conclude that being held in captivity after wild-capture eliminated naturally occurring differences between populations in oil droplet absorbance.

Differential expression of polymorphic alleles of the genes coding for the protein opsins that comprise the visual pigments are the key mechanisms underlying intraspecific variation in visual pigments observed in taxa other than birds. For example, in guppies, individuals within a population express a subset of four LWS and two SWS cone opsin alleles40,41. In New World monkeys, multiple alleles of a single sex-linked locus on the X-chromosome leads to dichromatic and trichromatic individuals within a population42. Environment43 and age44 can also influence expression of different alleles in primates. LWS visual pigment polymorphisms are sex linked in humans, and lead to red-green colour blindness in about 8% of men45, although evolutionary causes of human LWS polymorphisms remain contested46.

Our data on P. elegans alludes to subspecies differences in vision, but does not indicate the evolutionary origins of these differences. However, it is plausible that habitat differences could have been a contributory factor in the divergence of the plumage colouration in the P. elegans complex27. P. e. elegans is found in mesic wooded and forest habitats whereas P. e. flaveolus is found in more open riparian habitats dominated by Eucalyptus camaldulensis. In forests, ambient light contains reduced long wavelengths and appears green to yellow-green to the human eye when compared to ambient light in open habitats47. As such, one might expect animals living in forest shade to show shifts to shorter wavelengths in their visual pigment sensitivity in response to the ambient light, and this is the shift we observe in the LWS and MWS cones, and the rods of P. e. elegans when compared to P. e. flaveolus. The differences in λmax observed between P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus in LWS and MWS (Table 1) are close to, or larger than, the differences discovered between polymorphisms of the LWS visual pigment in humans, a difference which has been demonstrated many times to affect colour perception in colour matching experiments48. The ecological and behavioural factors that underlie the tuning of visual pigments in P. elegans, such as possible roles in mate choice, foraging, or navigation, remain to be determined. The significant differences in the λmax of the two cone visual pigments may lead to differences between our populations in their colour perception. Modelling to predict consequences for visual discrimination in P. elegans will need to consider filtering effects of the oil droplets (Fig. 3) plus the role of habitat light environments and background coloration which are likely to vary between habitats, along with the known plumage reflectances between the two subspecies. If the different visual pigments in the two subspecies did have negligible effects on visual discrimination, then the visual pigment difference would be likely due to genetic drift. However, even if the different visual pigments only have small effects on discrimination, or only in certain contexts, given enough time in the right environment they could still have selective effects, for as pointed out by Fisher49, even small differences in selective advantage will cause significant evolution.

Differences between populations in the λmax of the rod photoreceptors used for dim light vision are intriguing. The causes of this shift are difficult to assess given there is little understanding of the factors underlying the spectral tuning of rod photoreceptors2,50. During twilight, spectral irradiance of skylight is of greatest intensity between 450–500 nm47,51, and a rod λmax of approximately 500 nm, as observed in P. e. elegans, would be reasonably well adapted to vision in these conditions2. At night longer wavelengths of light become relatively more abundant, and a 500 nm λmax would no longer be optimal51. Potentially, the longer λmax of 506 nm observed in the P. e. flaveolus population could indicate a behavioural change in this subspecies to greater activity at dawn and dusk, where such a sensitivity shift would collect more light from leaves47 though any differences in activity between subspecies remains untested. However, even in nocturnal birds, rod λmax is usually located at approximately 500 nm52, even though longer wavelengths are more abundant51, so the causes of the intraspecific variation in the rods remain unclear. While few conclusions can be drawn from these data alone, the reported differences in rod λmax may be indicative of a behavioural shift in one subspecies, or an adaptation to maintain similar behaviours in different light environments. An alternative explanation could be that the observed λmax shift is a consequence of selection for a different aspect of opsin performance. For example, the λmax of avian rod visual pigments has been suggested to be a trade-off between optimal spectral sensitivity for dim light conditions, and resistance to ‘dark noise’ i.e. when an opsin is randomly activated by heat instead of light53. Potentially, the known differences in habitat between subspecies (flaveolus habitat is riverine) may mean the vision of one subspecies is more affected by dark noise than the other, so the opsins may have adapted to be more resistant. However, the general lack of knowledge of the factors influencing rod spectral sensitivity means any assessment of the differences in rod λmax are highly speculative.

Our earlier sequencing of retinal opsins of P. elegans28 revealed the full complement expected in birds3, namely four cone opsins (SWS1, SWS2, RH2 and LWS) and a single rod opsin, RH1. Those data28 came from another subspecies, P. e. adelaidae so their relevance to P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus may be limited, but they are the best data available on P. elegans. Consequently, we suggest it is likely P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus both only have SWS1, SWS2, RH2, LWS and RH1. We suggest the geographic differences in visual pigment tuning that we report here are most likely caused by divergence over time of the individual opsin genes for each visual pigment in each population, and not through differential expression of a subset of alleles. Potentially, the visual pigment sensitivity differences reported here may have arisen simply through isolation of the two populations which we sampled. However, previous analyses of the population genetics of the P. elegans complex suggest there is ongoing gene flow, little reproduction isolation between P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus subspecies, and the subspecies are not geographically isolated18,22. Given the correlation between an animal’s vision and its visual environment1, we suggest the divergence of visual pigment sensitivity between the P. e. elegans and P. e. flaveolus is unlikely simply through reproductive isolation, though whether or not the divergence is a consequence of differences in the visual environment remains unknown. As discussed for the rod visual pigment, the differences in λmax of the cones could also be a side effect of selection on a different aspect of visual pigment biochemistry, such as their resistance to dark noise. However, we suggest that such a change is likely to be generally advantageous to both subspecies and so we would expect the trait in both subspecies.

Conclusions

We reveal hitherto unknown diversity in the visual pigments of birds which, to date, had been regarded as highly conserved across taxa2,3. Additional MSP investigation to assess the extent of the divergence within and between the ranges of each subspecies will enable assessment of relationships between visual pigment sensitivity, visual environment, and the plumage colouration of the various subspecies of P. elegans. If a relationship is established, this could elucidate the role of the senses in speciation and the generation of biodiversity, because differences in perception of sexual signals can lead to further divergence of the signals, which can feedback to further divergence in vision27,33.

Taken together, our findings suggest that within-species differences in the physiology of vision may be more widespread than hitherto considered. As systematic investigation of within species differences in vertebrate vision have been so rarely attempted, our work suggests that testing and modelling such differences may be a fruitful area of future research. Classic examples of evolution from mimicry, to warning coloration and crypsis are usually tested on organisms such as insects which signal their coloration to birds as predators26,54 so improved understanding of factors tuning the avian eye – the most complex visual system of any vertebrate – will be of substantial value. Our findings have implications which range from better understanding of the role sensory processes play in divergence and speciation, to improved understanding of the evolution of the vertebrate eye and factors tuning its photoreceptors.

Methods

Subjects

Birds were caught from the wild at two populations, which represented two subspecies of P. elegans. Seven P. e. elegans were caught in Bellbrae, Victoria, Australia (S38°20′S, E144°16′S), and five P. e. flaveolus were caught near Mildura, Victoria, Australia (S34°25S, E142°18S). Birds were transported to Deakin University, Geelong, Australia and held for about 3 weeks (mean 25 days +/−27 SD) in outdoor flight cages on ad libitum parrot seed mix, fresh fruit and water, until retinal examination via MSP. For this, subjects were dark adapted for at least one hour before their humane killing.

Microspectrophotometry

Eyes were enucleated, and retinal tissue samples were prepared for MSP under infrared light using methods reported previously28,55. MSP was performed using a computer-controlled single beam device at Deakin University, Geelong, Australia. Measuring beams were aligned to pass transversely through the photoreceptor outer segment and run in 2 nm intervals from 750 nm to 350 nm, then back from 351 nm to 749 nm. After each measurement, the pigment was bleached with white light and the outer segment was rescanned to confirm the post-bleaching disappearance of the pigment and appearance of short-wavelength absorbing photoproducts. Oil droplet absorbance was measured using the same MSP scanning protocol, though with no post-scan bleaching.

λmax and λcut calculation

Prior to λmax calculation, all MSP records for each individual were randomly assigned to numbered files, such that the researcher calculating the λmax (BK) was blind to the population origin of any particular set of measurements. λmax was calculated from individual cell records for each pigment type using a standardised computer program29,56: briefly, absorbance values at pairs of adjacent wavelengths were averaged to obtain a mean curve from outward and return scans. λmax were calculated by fitting the 20 absorbance values on the long wavelength limb to a standard template curve57 to give an average λmax. This analysis effectively finds the spectral location of the standard curve that would produce the per cent absorbance values being considered28,29,56. For data selection purposes, a second estimate of λmax was obtained by fitting each of 50 absorbance points, centred on the peak of the averaged absorbance curve to the template curve, and averaging the results. Following λmax calculation, each cell record was subject to rigid selection criteria29. For LWS, MWS and rod pigments, spectra required a transverse density greater than 0.01, a standard deviation from the right hand limb of less than 12 nm, and a difference between the two estimation methods of less than 6 nm. For SWS and UVS, the criteria were relaxed due to the rarity of these cell types2, and any cells showing convincing evidence of post-measurement bleaching by white light were retained.

Oil droplet λcut were calculated using the method of Lipetz32. Briefly, a tangent is fitted to the droplet absorbance spectra at 50% maximum absorbance, and extrapolated. The wavelength at which the extrapolated tangent crosses the maximum measured absorbance of the spectra is the calculated λcut.

Geographic λmax and λcut comparison

For each population, records satisfying the selection criteria were analysed using SPSS 21 (SPSS Inc.). We analysed λmax data for each pigment type (LWS, MWS, SWS, UVS, rod) using linear mixed models (LMMs), with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. These models included a fixed effect for population/subspecies of origin (P. e. elegans or P. e. flaveolus), and a random intercept comprising bird ID. The random effect was included to account for non-independence of visual pigments measured from each bird. We report estimates of fixed effects and pairwise comparisons based on estimated marginal means resulting from these models. Significance of fixed effects was assessed using type-III sums of squares. λcut data were analysed using the same methods. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which is the ratio of variance between individuals to the total variance58, was calculated for each visual pigment type using type using intercepts-only mixed models.

For visualisation of the visual pigment absorbance spectra, visual pigments templates were produced using the mean values generated by the above analyses, using the methods of Govardovskii et al.59.

Ethics statement

All work was approved by Deakin University Animal Ethics Committee (approval no. G08–2012), and conducted under permit from the Victorian Department of Environment & Primary Industries (wildlife research permit no. 10006284). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Knott, B. et al. Intraspecific geographic variation in rod and cone visual pigment sensitivity of a parrot Platycercus elegans. Sci. Rep. 7, 41445; doi: 10.1038/srep41445 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Lythgoe, J. N. The Ecology of Vision. (Clarendon Press, 1979).

Hart, N. S. The visual ecology of avian photoreceptors. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 20, 675–703, doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(01)00009-X (2001).

Hart, N. S. & Hunt, D. M. Avian visual pigments: Characteristics, spectral tuning, and evolution. American Naturalist 169, S7–S26, doi: 10.1086/510141 (2007).

Carvalho, L. D., Cowing, J. A., Wilkie, S. E., Bowmaker, J. K. & Hunt, D. M. Shortwave visual sensitivity in tree and flying squirrels reflects changes in lifestyle. Current Biology 16, R81–R83, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.045 (2006).

Cowing, J. A., Poopalasundaram, S., Wilkie, S. E., Bowmaker, J. K. & Hunt, D. M. Spectral tuning and evolution of short wave-sensitive cone pigments in cottoid fish from Lake Baikal. Biochemistry 41, 6019–6025, doi: 10.1021/bi025656e (2002).

Hunt, D. M. et al. Molecular evolution of trichromacy in primates. Vision Research 38, 3299–3306, doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00443-4 (1998).

Parry, J. W. L. et al. Mix and match color vision: Tuning spectral sensitivity by differential opsin gene expression in Lake Malawi Cichlids. Current Biology 15, 1734–1739, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.010 (2005).

Archer, S. N., Endler, J. A., Lythgoe, J. N. & Partridge, J. C. Visual pigment polymorphism in the guppy Poecilia reticulata . Vision Research 27, 1243–1252, doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90200-8 (1987).

Fuller, R. C., Fleishman, L. J., Leal, M., Travis, J. & Loew, E. Intraspecific variation in retinal cone distribution in the bluefin killifish, Lucania goodei. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 189, 609–616, doi: 10.1007/s00359-003-0435-x (2003).

Jacobs, G. H., Bowmaker, J. K. & Mollon, J. D. Behavioral and microspectrophotometric measurements of color vision in monkeys. Nature 292, 541–543, doi: 10.1038/292541a0 (1981).

Mollon, J. D., Bowmaker, J. K. & Jacobs, G. H. Variations of color vision in a New World primate can be explained by polymorphism of retinal photopigments. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 222, 373–399, doi: 10.1098/rspb.1984.0071 (1984).

Morgan, M. J., Adam, A. & Mollon, J. D. Dichromats detect color-camouflaged objects that are not detected by trichromats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 248, 291–295, doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0074 (1992).

Nathans, J., Thomas, D. & Hogness, D. S. Molecular genetics of human color vision: the genes encoding blue, green, and red pigments. Science 232, 193–202, doi: 10.1126/science.2937147 (1986).

Forshaw, J. & Cooper, W. T. Australian Parrots. 3rd Edition edn (Robina Press, 2002).

Cain, A. J. A revision of Trichoglossus haematodus and of the Australian Platycercine parrots. Ibis 97, 432–479, doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1955.tb04978.x (1955).

Irwin, D. E. & Irwin, J. H. Circular overlaps: Rare demonstrations of speciation. Auk 119, 596–602, doi: 10.2307/4089961 (2002).

Mayr, E. Animal Species and Evolution. (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1963).

Joseph, L. et al. Where and when does a ring start and end? Testing the ring-species hypothesis in a species complex of Australian parrots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 275, 2431–2440, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0765 (2008).

Ribot, R. F. H., Berg, M. L., Buchanan, K. L. & Bennett, A. T. D. Fruitful use of bioacoustic alarm stimuli as a deterrent for Crimson Rosellas (Platycercus elegans). Emu 111, 360–367, doi: 10.1071/mu10080 (2011).

Ribot, R. F. H., Berg, M. L., Buchanan, K. L. & Bennett, A. T. D. Is there variation in the response to contact call playbacks across the hybrid zone of the parrot Platycercus elegans? Journal of Avian Biology 44, 399–407, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2013.00163.x (2013).

Ribot, R. F. H. et al. Does the ring species concept predict vocal variation in the crimson rosella, Platycercus elegans, complex? Animal Behaviour 77, 581–593, doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.10.029 (2009).

Ribot, R. F. H. et al. Learned Vocal Variation Is Associated with Abrupt Cryptic Genetic Change in a Parrot Species Complex. PloS one 7, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050484 (2012).

Mihailova, M., Berg, M. L., Buchanan, K. L. & Bennett, A. T. D. Odour-based discrimination of subspecies, species and sexes in an avian species complex, the crimson rosella. Animal Behaviour 95, 155–164, doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.07.012 (2014).

Eastwood, J. R. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of beak and feather disease virus across a host ring-species complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 14153–14158, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403255111 (2014).

Berg, M. L. & Bennett, A. T. D. The evolution of plumage colouration in parrots: a review. Emu 110, 10–20, doi: 10.1071/mu09076 (2010).

Bennett, A. T. D., Cuthill, I. C. & Norris, K. J. Sexual selection and the mismeasure of color. American Naturalist 144, 848–860, doi: 10.1086/285711 (1994).

Endler, J. A. Sensory drive: does sensory biology bias or constrain the direction of evolution? American Naturalist 139, S125–S153 (1992).

Knott, B. et al. How parrots see their colours: novelty in the visual pigments of Platycercus elegans . Journal of Experimental Biology 216, 4454–4461, doi: 10.1242/jeb.094136 (2013).

Bowmaker, J. K., Heath, L. A., Wilkie, S. E. & Hunt, D. M. Visual pigments and oil droplets from six classes of photoreceptor in the retinas of birds. Vision Research 37, 2183–2194, doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00026-6 (1997).

Carvalho, L. S., Knott, B., Berg, M. L., Bennett, A. T. D. & Hunt, D. M. Ultraviolet-sensitive vision in long-lived birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 278, 107–114, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1100 (2011).

Knott, B., Bowmaker, J. K., Berg, M. L. & Bennett, A. T. D. Absorbance of retinal oil droplets of the budgerigar: sex, spatial and plumage morph-related variation. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 198, 43–51, doi: 10.1007/s00359-011-0684-z (2012).

Lipetz, L. E. A new method for determining peak absorbance of dense pigment samples and its application to the cone oil droplets of Emydoidea blandingii . Vision Research 24, 597–604, doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(84)90114-7 (1984).

Pearn, S. M., Bennett, A. T. D. & Cuthill, I. C. The role of ultraviolet-A reflectance and ultraviolet-A induced fluorescence in the appearance of budgerigar plumage: insights from spectrofluorometry and reflectance spectrophotometry. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 270, 859–865, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2315 (2003).

Endler, J. A. Signals, Signal Conditions, and the Direction of Evolution. American Naturalist 139, S125–S153, doi: 10.1086/285308 (1992).

Bowmaker, J. K. Visual Pigments, Oil Droplets and Spectral Sensitivity of Pigeon. Vision Research 17, 1129–1138, doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(77)90147-X (1977).

Hart, N. S., Lisney, T. J. & Collin, S. P. Cone photoreceptor oil droplet pigmentation is affected by ambient light intensity. Journal of Experimental Biology 209, 4776–4787, doi: 10.1242/jeb.02568 (2006).

Knott, B. et al. Avian retinal oil droplets: dietary manipulation of colour vision? Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 277, 953–962, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1805 (2010).

Vorobyev, M. Coloured oil droplets enhance colour discrimination. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 270, 1255–1261, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2381 (2003).

Vorobyev, M., Osorio, D., Bennett, A. T. D., Marshall, N. J. & Cuthill, I. C. Tetrachromacy, oil droplets and bird plumage colours. Journal of Comparative Physiology a-Neuroethology Sensory Neural and Behavioral Physiology 183, 621–633, doi: 10.1007/s003590050286 (1998).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Opsin gene duplication and diversification in the guppy, a model for sexual selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 274, 33–42, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3707 (2007).

Ward, M. N. et al. The molecular basis of color vision in colorful fish: Four Long Wave-Sensitive (LWS) opsins in guppies (Poecilia reticulata) are defined by amino acid substitutions at key functional sites. Bmc Evolutionary Biology 8, doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-210 (2008).

Jacobs, G. H., Neitz, M., Deegan, J. F. & Neitz, J. Trichromatic colour vision in New World monkeys. Nature 382, 156–158, doi: 10.1038/382156a0 (1996).

Fuller, R. C., Carleton, K. L., Fadool, J. M., Spady, T. C. & Travis, J. Genetic and environmental variation in the visual properties of bluefin killifish, Lucania goodei. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 18, 516–523, doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00886.x (2005).

Temple, S. E., Veldhoen, K. M., Phelan, J. T., Veldhoen, N. J. & Hawryshyn, C. W. Ontogenetic changes in photoreceptor opsin gene expression in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch, Walbaum). Journal of Experimental Biology 211, 3879–3888, doi: 10.1242/jeb.020289 (2008).

Sharpe, L. T., Stockman, A., Jägle, H. & Nathans, J. In Color Vision: From Genes to Perception (eds Gegenfurtner, K. R. & Sharpe, L. T. ) (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Jacobs, G. H. Evolution of colour vision in mammals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 364, 2957–2967, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0039 (2009).

Endler, J. A. The color of light in forests and its implications. Ecological Monographs 63, 1–27, doi: 10.2307/2937121 (1993).

Neitz, J. & Jacobs, G. H. Polymorphism of the long-wavelength cone in normal human color vision. Nature 323, 623–625, doi: 10.1038/323623a0 (1986).

Fisher, R. A. The genetical theory of natural selection. (Clarendon Press, 1930).

Hunt, D. M., Carvalho, L. S., Cowing, J. A. & Davies, W. L. Evolution and spectral tuning of visual pigments in birds and mammals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 364, 2941–2955, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0044 (2009).

Munz, F. W. & McFarland, W. N. Significance of spectral position in rhodopsins of tropical marine fishes. Vision Research 13, 1829–1874, doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(73)90060-6 (1973).

Bowmaker, J. K. & Martin, G. R. Visual pigments and color vision in a nocturnal bird, Strix aluco (tawny owl). Vision Research 18, 1125–1130, doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90095-0 (1978).

Barlow, H. B. Purkinje shift and retinal noise. Nature 179, 255–256, doi: 10.1038/179255b0 (1957).

Church, S. C. et al. Does lepidopteran larval crypsis extend into the ultraviolet? Naturwissenschaften 85, 189–192, doi: 10.1007/s001140050483 (1998).

Yewers, M. S. et al. Spectral sensitivity of cone photoreceptors and opsin expression in two colour-divergent lineages of the lizard Ctenophorus decresii. Journal of Experimental Biology 218, 1556–1563, doi: 10.1242/jeb.119404 (2015).

Davies, W. L. et al. Shedding Light on Serpent Sight: The Visual Pigments of Henophidian Snakes. Journal of Neuroscience 29, 7519–7525, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0517-09.2009 (2009).

Knowles, A. & Dartnall, H. J. A. In The eye (ed Davson, H. ) 689 (Academic Press, New York, 1977).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using multivariate statistics. 5th edn (Pearson, 2007).

Govardovskii, V. I., Fyhrquist, N., Reuter, T., Kuzmin, D. G. & Donner, K. In search of the visual pigment template. Visual Neuroscience 17, 509–528, doi: 10.1017/S0952523800174036 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kate Buchanan, Justin Eastwood and various landowners, particularly Minter Farm for assistance with fieldwork. This work was funded by Australian Research Council (ARC) grant LP140100691 to ATDB. BK was funded by Deakin University, MLB was funded by the ARC and Deakin University and RFHR by BHP Billiton and Deakin University. We are grateful to the Centre for Integrative Ecology, for additional funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K.: performed the microspectrophotometry, analyses of visual pigment absorbance spectra, and prepared the manuscript. M.L.B.: assisted with statistical analyses and manuscript preparation; discussed implications of pigment differences. R.F.H.R.: assisted with fieldwork and manuscript preparation. J.A.E.: created visual models, discussed implications of pigment differences, and assisted with manuscript preparation. A.T.D.B.: conceived, managed and oversaw the project, provided funding and equipment, captured the birds, discussed implications of pigment differences, was principal investigator of P. elegans research grants, and assisted with manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Knott, B., Berg, M., Ribot, R. et al. Intraspecific geographic variation in rod and cone visual pigment sensitivity of a parrot, Platycercus elegans. Sci Rep 7, 41445 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41445

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41445

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.