Abstract

Programmed necrosis (necroptosis) is an alternative form of programmed cell death that is regulated by receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 1 and 3-dependent, but is a caspase (CASP)-independent pathway. In the present study, to determine if necroptosis participates in bovine structural luteolysis, we investigated RIPK1 and RIPK3 expression throughout the estrous cycle, during prostaglandin F2α (PGF)-induced luteolysis in the bovine corpus luteum (CL), and in cultured luteal steroidogenic cells (LSCs) after treatment with selected luteolytic factors. In addition, effects of a RIPK1 inhibitor (necrostatin-1, Nec-1; 50 μM) on cell viability, progesterone secretion, apoptosis related factors and RIPKs expression, were evaluated. Expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 increased in the CL tissue during both spontaneous and PGF-induced luteolysis (P < 0.05). In cultured LSCs, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF; 2.3 nM) in combination with interferon γ (IFNG; 2.5 nM) up-regulated RIPK1 mRNA and protein expression (P < 0.05). TNF + IFNG also up-regulated RIPK3 mRNA expression (P < 0.05), but not RIPK3 protein. Although Nec-1 prevented TNF + IFNG-induced cell death (P < 0.05), it did not affect CASP3 and CASP8 expression. Nec-1 decreased both RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein expression (P < 0.05). These findings suggest that RIPKs-dependent necroptosis is a potent mechanism responsible for bovine structural luteolysis induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many species, the corpus luteum (CL) is a transient endocrine gland responsible for the secretion of progesterone (P4), a sex steroids that is essential for establishment and maintenance of pregnancy1. When animals do not become pregnant, regression of the CL, called luteolysis, is essential for normal cyclicity because it allows the development of new follicles. Luteolysis in ruminant species results from the uterine release of prostaglandin F2α (PGF)2. In cattle, luteolysis can also be pharmacologically induced by administration of PGF analogs by injection. Luteolysis involves reduction in P4 production (functional luteolysis) and tissue degradation by cell death (structural luteolysis)3,4. Generally, caspase-dependent apoptosis, also known as type I programmed cell death5, in the cells that form the CL, such as luteal steroidogenic cells (LSC) and luteal endothelial cells (LEC), is thought to be the predominant pathway for cell death during luteolysis in several species including cattle3,4. A large number of factors have been implicated in structural and functional regression of bovine CL6,7,8,9,10,11. Apoptosis of luteal cells and CL vascular regression are regulated/modulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines, i.e., tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), interferon-γ (IFNG), FAS ligand (FASL) and nitric oxide (NO)6,7,8,9,10. On the other hand, P4, cortisol and luteotropic PGs (PGE2 and PGI2) protect LSCs against apoptosis11,12,13. As mentioned above, apoptosis in CL is regulated by complex mechanisms inducing a cascade of several immune-endocrine factors and mediators.

Apoptosis occurs through two main signaling cascades, which are known as the death receptor pathway and the mitochondrial pathway14,15. The death receptor pathway, which is also known as the extrinsic apoptotic route, is initiated by extracellular signals (e.g., FasL, TNFα) that interact with cell surface receptors (e.g., Fas, TNFRs) that are responsible for transduction of cell death signaling14. On the other hand, the mitochondrial pathway, which is also called the intrinsic apoptotic cascade, is regulated by members of the Bcl-protein family. The relative ratio of Bcl-2, which protects against cell death, and Bax, a proapoptotic protein, determines cell fate15. These two pathways are not completely separated and share part of signals. In fact, both of these pathways are characterized by activation of caspases (CASPs), which are intracellular cysteine aspartic proteases16. Death ligands, such as TNF and FASL, when bound to the death receptor expressed on cell membranes, can activate an upstream CASP named CASP8. CASP8 (activated CASP) induces downstream executor CASPs including CASP3, finally resulting in DNA fragmentation and apoptosis17. During the past several decades, apoptosis is considered to be the most studied local mechanism regulating structural luteolysis of the bovine CL. Thus, a great number of studies have been focused on type-I programmed cell death of steroidogenic and accessory luteal cells6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. However, luteolysis, especially exogenous PGF-induced luteolysis, is a very rapid process and the bovine CL completely disappears from the ovary within 2 days after PGF injection. Thus, one may consider that apoptosis alone is not a sufficient mechanism to induce this acute luteolysis.

There are also caspase-independent cell death pathways, which are involved in homeostasis of different tissues and organs18. Necrosis is one cell death mechanism known to be caspase-independent. Generally, necrosis has been considered as an accidental and undesirable cell demise pathway. Furthermore, it is carried out in a non-regulated manner and caused by extreme conditions. However, recently it was reported that necrosis can be regulated by intracellular mechanisms19. When apoptosis is blocked by caspase inhibitors such as zVAD-FMK, the necroptosis pathway, which is an alternative cell death pathway, is activated18,20,21. Receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 1 and RIPK3 are known to play roles as sensors of cellular stress22 and are essential kinases mediating the programmed necrosis pathway21,23,24,25. Moreover, death ligands such as TNF and Fas ligand induce not only apoptosis but also necrosis in a number of tissues26,27. RIPK1 binds to members of the TNF receptor super family such as TNFR1, FAS, tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAILR) 1 and TRAILR2, and is crucial in the necroptotic pathway induced by these TNF receptor super family members26. Indeed, RIPK3 is also known to be a necessary modulator for necroptosis23,24,25,27. There are several reports about necroptosis mediated by TNF receptor (TNFR) type 125,27,28, and it is also reported that TNFR1 and FAS, which are members of the TNF receptor super family, play important roles in cell death in bovine LSCs7. Therefore, we hypothesized that necroptosis occurs in bovine LSC and contributes to luteolysis. However, it is still unclear whether necroptosis is one of the mechanisms responsible for structural regression of the bovine CL.

In the present study, to test the hypothesis that necroptosis serves as a necessary and/or accessory mechanism for CL cell death during luteolysis in the cow, we investigated: (1) the expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in bovine CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle and during PGF-induced luteolysis in vivo, (2) the local regulatory mechanism of RIPKs expression in luteal cells, and (3) the participation of RIPKs in LSC death mechanisms by using an in vitro cell culture system with necrostatin-1 (Nec-1), an allosteric inhibitor of RIPK1 activity.

Results

Changes in RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein expression throughout the estrous cycle and PGF-induced luteolysis in vivo

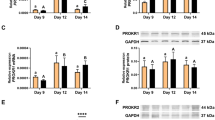

To clarify the presence of necroptosis, the expression of necroptosis main inducer RIPK1 and RIPK3 in bovine CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle and during PGF-induced luteolysis were investigated by real-time PCR and western blotting. Real-time PCR analysis showed that expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA in bovine CL tissues was present throughout the luteal stages of the cycle and was estrous cycle dependent. RIPK1 mRNA expression (RIPK1 mRNA/GAPDH mRNA ratio) increased after the mid luteal stage until regression (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05) and the highest RIPK3 mRNA expression was found at the regressed luteal stage (Fig. 1B; P < 0.05). Expression of both RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein was low during early to mid luteal stages, and increased significantly at the late luteal stage (Fig. 1C and D; P < 0.05). RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA expression levels were higher 4 h and 12 h after PGF injection (Fig. 2A and B; P < 0.05), compared to the control. RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein expression was higher 4 h after PGF injection than in the control (Fig. 2C and D; P < 0.05). Full length lanes of western blotting are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Changes in the relative amounts of RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein expression in the bovine CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle.

(A) and (B) Comparison of relative amounts of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA determined by quantitative RT-PCR in bovine CL tissue throughout the estrous cycle (early: Days 2–3; developing: Days 5–6; mid: Days 8–12; late: Days 15–17; regressed luteal stages: Days 19–21). Data are the mean ± SEM for four samples/stage and are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA to GAPDH mRNA. (C) and (D) Representative western blot bands for RIPK1 or RIPK3 and ACTB. Densitometrically analyzed western blot results in bovine CL tissue during different luteal phases. Data are the mean ± SEM for four samples/stage and are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 protein to ACTB protein. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05), as determined by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

Changes in the relative amounts of RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein expression in the bovine CL tissues during PGF-induced luteolysis.

(A) and (B) Comparison of relative amounts of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA determined by quantitative RT-PCR in bovine CL tissue after PGF administration (0 h: control; 2 h, 4 h and 12 h). Data are the mean ± SEM for four samples/stage and are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA to GAPDH mRNA. (C) and (D) Representative western blot bands for RIPK1 or RIPK3 and ACTB. Densitometrically analyzed western blot results in bovine CL tissue during different luteal phases. Data are the mean ± SEM for four samples/stage and are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 protein to ACTB protein. The data were statistically analyzed by a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Different superscript letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Then, to investigate the localization of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in bovine CL tissue, immunohistochemistry was performed. For both RIPK1 and RIPK3 antibodies, whole tissue, especially luteal endothelial cells (arrowhead), showed positive staining at the regressed luteal stage and 12 h after PGF injection (Figs 3C,F and 4C,F).

Localization of RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein in the bovine CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle.

Representative images of localization of RIPK1 (A–C) and RIPK3 (D–F) protein in bovine CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle. Each small window shows a negative control stained with normal rabbit IgG instead of primary antibody. Bar = 25 μm.

Localization of RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein in the bovine CL tissues during PGF-induced luteolysis.

Representative images of localization of RIPK1 (A–C) and RIPK3 (D–F) protein in bovine CL tissues during PGF-induced luteolysis. Each small window shows a negative control stained with normal rabbit IgG instead of primary antibody. Bar = 25 μm.

Expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 in LSCs and LECs, and local regulatory mechanisms of RIPK1 and RIPK3 expression in cultured LSCs

As a preliminary study, RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA expression was confirmed by RT-PCR in isolated LSCs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To investigate the regulator for the RIPKs expression in bovine LSCs, cells were treated with several luteolytic factors 12 or 24 h. Then real-time RT-PCR and western blotting were performed. Treatment with TNF in combination with IFNG highly up-regulated the expression of RIPK1 mRNA (Fig. 5A and C; up to 243% and 528% of the control at 12 and 24 h, respectively; P < 0.05). RIPK3 mRNA was up-regulated by TNF + IFNG at 12 h (Fig. 5B; up to 323% of control value; P < 0.05). However, this effect was no longer evident in the cells after 24 h incubation with the cytokines (Fig. 5D; P > 0.05). The NO donor and PGF did not affect directly RIPKs expression at the gene level at any time of treatment (P > 0.05). Therefore, in the next study at the protein level, only the combined treatment with TNF and IFNG was used.

Confirmation of materials and adequate time to influence RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and expression effects of TNF and IFNG on the expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 protein in cultured luteal steroidogenic cells (LSCs).

LSCs were treated with TNF (2.3 nM) and/or IFNG (2.5 nM), PGF (1.0 μM) or NONOate (100 μM) for 12 and 24 h. (A) and (C) show the expression of RIPK1 mRNA, and (B) and (D) show the expression of RIPK3 in the LSCs after culture for 12 and 24 h, respectively. Data are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA to GAPDH mRNA levels. All values are the means ± SEM. All of the experiments were repeated more than three times. The data were statistically analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with control (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01, respectively). (E) and (F) show representative western blot bands for RIPK1 or RIPK3 and ACTB in cells treated with TNF (2.3 nM) and IFNG (2.5 nM) for 24 h. The resulting signal was visualized using the alkaline phosphatase visualization procedure and quantitated by computer-assisted densitometry. Data are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 protein to ACTB protein. All values are the means ± SEM. All of the experiments were repeated more than three times. The data were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with control for 24 h (P < 0.05).

Treatment with TNF in combination with IFNG up-regulated the expression of RIPK1 protein but not RIPK3 protein in LSCs cultured for 24 h (Fig. 5E and F; P < 0.05).

Effects of Nec-1 on function of the cultured LSCs

To clarify the role of RIPKs on function in LSCs, cells were exposed to Nec-1, which is an inhibitor for RIPK1 activity, with or without TNF + IFNG. Thereafter, cell viability and P4 secretion were measured. While a single treatment with Nec-1 did not affect LSCs viability, it prevented cell death induced by TNF + IFNG in the LSCs (Fig. 6A). Nec-1 did not affect P4 production (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Effects of necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) on cell viability and expression of intracellular apoptosis related factors in luteal steroidogenic cells (LSCs).

(A) The cells were treated with TNF (2.3 nM) + IFNG (2.5 nM) in combination with Nec-1 (50 μM) for 24 h. After culture, cell viability was measured. In this assay, data were expressed as percentages of the appropriate control values. All values are the means ± SEM. All experiments were repeated more than three times. The data were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test. Asterisk (*) indicates significant differences (P < 0.05) compared to control, and hash (#) indicates significant differences between the presence and absence of Nec-1 (P < 0.05). Comparison of relative amounts of CASP3 (B), CASP8 (C), BAX (D) or BCL2 (E) mRNA determined by quantitative RT-PCR in the LSC after treatment with Nec-1 (50 μM) and/or TNF (2.3 nM) + IFNG (2.5 nM) for 12 h. All experiments were repeated more than three times. The data were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test. Asterisk (*) indicates significant differences compared to control (P < 0.05).

To confirm the pathway of cell death, i.e., apoptotic pathway or necroptotic pathway, real-time PCR and western blotting were performed after treatment of Nec-1 with or without TNF + IFNG in LSCs. Nec-1 did not affect TNF + IFNG-induced CASP-3 and CASP-8 expression (Fig. 6B and C). BCL2 mRNA expression was down-regulated by a single treatment with Nec-1 (Fig. 6E). TNF and IFNG-induced RIPK1 mRNA and protein expression was down-regulated by Nec-1 (Fig. 7A and C; P < 0.05). Furthermore, TNF + IFNG-induced RIPK3 mRNA and protein expression was down-regulated by Nec-1 treatment (Fig. 7B and D; P < 0.05). Full length lanes of western blotting are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Effects of Nec-1 on the expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein in luteal steroidogenic cells (LSCs).

(A) and (B) Comparison of relative amounts of RIPK1 or RIPK3 mRNA determined by quantitative RT-PCR in bovine LSCs after treatment with Nec-1 (50 μM) and/or TNF (2.3 nM) + IFNG (2.5 nM) for 12 h. (C) and (D) Representative western blot bands for RIPK1 or RIPK3 and ACTB in cells treated with Nec-1 (50 μM) and/or TNF (2.3 nM) + IFNG (2.5 nM) for 24 h. The resulting signal was visualized using the alkaline phosphatase visualization procedure and quantitated by computer-assisted densitometry. Data are expressed as the relative ratio of RIPK1 or RIPK3 protein to ACTB protein. All values are the means ± SEM. All experiments were repeated more than three times. Asterisk (*) indicates significant differences compared to control (P < 0.05), and hash (#) indicates significant differences between the presence and absence of Nec-1 (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Until now, there were no reports indicating that caspase-independent cell death can occur in the bovine CL during the course of luteolysis. In the present study, we proposed a new luteolytic mechanism responsible for steroidogenic cell death and elimination from bovine CL, i.e., RIPK-dependent necroptosis. Caspase-dependent apoptosis, which is induced by binding of death ligands to death receptors on the cell membrane, is known as a typical programmed cell death mechanism16,17 Cell-death receptors such as TNFR super family receptors are activated by binding death ligands. Thereafter, cytoplasm CASPs are recruited to death receptors and activated, and result in cell elimination during luteolysis via apoptosis17. In contrast, activated death receptors are known to recruit not only CASPs but also RIPKs25,26,28. After recruitment of RIPKs by death receptors, if deubiquitination of RIPKs by intracellular factors, such as cylindromatosis (CYLD), occurs, RIPKs form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) II that results in cell death by necroptosis29. In the present study, we have shown that RIPK1 and RIPK3 expression is strongly elevated in the bovine CL during spontaneous or PGF-induced luteolysis. Our results clearly showed that RIPKs-dependent necroptosis plays important roles in bovine structural luteolysis.

Cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (cFLIP) may be a candidate intracellular factor regulating RIPK activation and necroptosis30. Cellular FLIP was originally described as a regulator of death receptor-mediated apoptosis31. At the protein level, it occurs in two endogenous forms, cFLIP long (cFLIPL) and cFLIP short32, and it was reported that the CASP8-cFLIPL complex inhibits not only apoptosis but also RIPK-dependent necroptosis32,33. Our recent report showed that cFLIPL is expressed throughout the estrous cycle in bovine CL tissues and decreased in regressed CL34. These findings and the present study suggest that cFLIPL down-regulates expression of RIPKs and inhibits necroptosis in the bovine CL during early to late luteal stages.

Detection of RIPKs localization in bovine LSCs and LECs by immunohistochemistry suggests the possibility that RIPKs-dependent necroptosis occurs in these cells. To clarify the mechanisms of necroptosis in these cells and during luteolysis, as the first step, we investigated the regulatory mechanisms of RIPKs expression in bovine LSCs. Since administration of PGF up-regulated both RIPK1 and RIPK3 in vivo, this may imply that PGF or some intra-luteal factors which mediate PGF action are crucial stimulators for RIPKs expression. The effect of PGF, which is known to be the most common luteolytic factor, was investigated both in vivo and in vitro, and the local effects of PGF on luteal function are very complex2,3,13,28,35,36. Based on the above findings, it is clear that the luteolytic effect of PGF is not directly upon LSCs and LECs to induce cell death, but it depends on cell composition and contact37. In the present study, PGF did not affect RIPKs mRNA expression in a pure population of cultured LSCs. Therefore, it could be concluded that the luteolytic action of PGF on bovine CL in vivo is mediated by several auto/paracrine factors which activate luteolytic mechanisms responsible for structural and functional luteal regression38. Similarly, the effect of PGF on RIPKs expression might depend on some mediators or upon cell composition and contact. Nitric oxide induces luteolysis in vivo, and stimulates CASP3 activity and apoptosis in cultured LSCs8,39,40. On the other hand, NO inhibits CASP3 activity and apoptosis in various types of cells41,42,43. Thus, NO plays both roles, inhibiting or stimulating programmed cell death depending on the cell type. In the present study, we investigated the effect of NO on RIPKs expression, and an NO donor, NONOate, did not affect mRNA expression of both RIPK1 and RIPK3. The experimental design that we used in the present study could not clarify the effect of PGF and NO on RIPKs expression in LSCs. Further studies are needed to determine the effects of NO as well as PGF on RIPKs expression and necroptosis in bovine LSCs.

During luteolysis, it is known that the number of immune cells (e.g., T lymphocytes, macrophages) increases in the bovine CL44. The immune cells produce a variety of cytokines, including TNF and IFNG, which have been shown to induce functional and structural luteolysis in the cow2,9,45,46. It has been found that TNF superfamily ligands (FAS ligand and TNF) can stimulate RIPK-dependent necroptosis in several types of cells such as human T cells and mouse dendritic cells24,25,26. However, treatment with TNF alone did not stimulate RIPKs mRNA expression in the present study. Furthermore, although type I IFNs, such as IFN α and β, can stimulate necroptosis in cancer cells and macrophages47,48, a single treatment with IFNG also did not affect RIPKs mRNA expression in bovine LSCs. IFNG induces expression of TNF superfamily receptors in several cells10,49,50 including bovine LSCs7, and the combination of TNF and IFNG can stimulate acute apoptosis and luteolysis7,10,51. Based on the above findings, we hypothesized that TNF in combination with IFNG can stimulate RIPK-dependent cell death. As expected, treatment with TNF in combination with IFNG increased RIPK1 mRNA expression significantly at 12 and 24 h. Moreover, TNF + IFNG upregulated RIPK1 protein expression, suggesting that TNF is a crucial regulator for RIPK1 as well as IFNG in bovine LSCs. Although RIPK3 mRNA was up-regulated by TNF and IFNG at 12 h, RIPK3 protein did not increase after treatment with TNF and IFNG. This contradiction is thought to be caused by the time lag between transfer and translation or adjustment at the translation stage. Thus, the combination of TNF and IFNG was revealed as an important stimulator for RIPKs, particularly RIPK1, expression in bovine LSCs.

Moreover, for final confirmation that RIPKs-dependent cell death is involved in TNF + IFNG-induced death in LSCs, we used Nec-1 which inhibits the kinase activity of RIPK1 and prevents RIPK1/RIPK3 interaction21,24. Apoptosis occurs through two main signaling cascades, namely, the extrinsic apoptotic route and intrinsic apoptotic cascade14,15. Some studies have revealed that TNF and IFNG strongly stimulate the extrinsic apoptotic route via stimulating several cytokine receptors, such as TNFRI and FAS, in bovine LSCs6,7,9,10. Furthermore, another major apoptotic pathway, the intrinsic apoptotic cascade, is regulated by members of the Bcl-protein family, which is composed of antiapoptotic (e.g., Bcl-2) and proapoptotic (e.g., Bax) proteins4,15,52. In both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic routes, CASP3 is a pivotal executioner for apoptosis18. In the present study, Nec-1 prevented spontaneous Bcl-2 mRNA expression, but not expression of TNF + IFNG-induced CASP8 and CASP3 mRNA, revealing that Nec-1 did not affect CASPs-dependent apoptosis in bovine LSCs. Additionally, while Nec-1 did not affect CASP3 mRNA expression, it could rescue LSCs from TNF + IFNG-induced cell death, strongly suggesting that the RIPKs-dependent necroptosis pathway is involved in TNF + IFNG-induced cell death in bovine LSCs. In addition, TNF is also reported to stimulate cell death in human luteal cells53 and luteal cell death induces the luteolysis in human51. It was demonstrated that TNF-induced cell death is apoptosis53 and it has never reported the presence of necroptosis in human luteal cells. The present results may contribute to the development of research for cell death of luteal cells and luteolysis in human.

Furthermore, Nec-1 increased cell viability but not P4 secretion, suggesting that Nec-1 prevention of cell death is not mediated/modulated by P4, which prevents apoptosis in bovine LSCs3,11,54. Taken together, TNF + IFNG-induced cell death in bovine LSCs may be regulated not only by CASP-dependent apoptosis but also by RIPK-dependent necroptosis. The results concerning expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 invite us to examine details of the cascade of necroptosis in bovine LSCs. Generally, RIPK1 is thought to have a crucial role in recruiting and activating RIPK324,55. Meanwhile, RIPK3 is also reported to be activated by TNF in the absence of RIPK128, or that RIPK1 can inhibit RIPK3-dependent necroptosis56. The question whether RIPK1 is essential for regulation of RIPK3 expression in the bovine CL is still open. However, it has been shown in several reports that during RIPK-dependent necroptosis the activity of RIPKs is highly increased without any changes in their gene expression20,22,23,24,55,56. Thus, as a result of our findings it might be thought that, although RIPK1 does not affect RIPK3 expression in bovine LSCs, necroptosis is regulated by changes in RIPKs expression in these cells.

This study demonstrated for the first time the expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3, and the presence of RIPKs-dependent cell death, in the bovine CL both in vivo and in vitro. These findings suggest that RIPKs-dependent cell death can be a potent mechanism of TNF- and IFNG-mediated CL regression in cattle. Schematic representation of possible mechanisms to induce cell death in the bovine LSCs is shown in Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of possible mechanisms to induce cell death in the bovine LSCs.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IFNG, can induce at least two cell death pathway, i.e., CASPs-dependent apoptotic pathway and RIPKs-dependent necroptotic pathway, in the bovine LSCs. Apoptotic pathway is mediated by CASP8 and CASP3, BAX and Bcl-2 can play as inducer and inhibitor of apoptotic pathway, respectively. In necroptotic pathway, RIPK1 and RIPK3 play central role to induce cell death. RIPK1 inhibitor, Nec-1, can inhibit necroptotic pathway. Both CASPs-dependent apoptosis and RIPKs-dependent necroptosis can be potent mechanisms of luteolysis in cattle.

Methods

Animal procedures

All in vivo experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines: EU Directive of the European Parliament and the Council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (22 September 2010; No 2010/63/EU), Polish Parliament Act on Animal Protection (21 August 1997, Dz.U. 1997 nr 111 poz. 724) with further novelization - Polish Parliament Act on the protection of animals used for scientific or educational purposes (15 January 2015, Dz.U. 2015 poz. 266). All animal procedures were approved and accepted accordingly to relevant guidelines by the Local Ethics Committee for Experiments on Animals in Olsztyn, Poland (Agreement No. 85/2012).

For determination of expression of RIPKs throughout the estrous cycle, CLs from normally cycling cows were obtained from a local abattoir. Luteal stages were confirmed as being early (Days 2–3 after ovulation: n = 4), developing (Days 5–7: n = 4), mid (Days 10–12: n = 4), late (Days 15–17: n = 4) and regressed (Days 19–21: n = 4) by additional macroscopic observation of the ovary and uterus as described previously57.

For cell culture, ovaries with CLs (Day 10–12 of the cycle) were submerged in ice-cold physiological saline and transported to the laboratory.

To determine the effect of PGF on expression of RIPKs, ovaries with CL were taken out via vagina (colpotomy) using a Hauptner’s effeninator (Hauptner & Herberholz GmbH & Co. KG, Solingen, Germany) on Day 10 post-ovulation, i.e., non-treated (0 h, control: n = 4), and at 2- (n = 4), 4- (n = 4) and 12-h (n = 4) after injection of a luteolytic dose of PGF analog (dinoprost, i.m.: 5 mg; as recommended by the manufacturer) as described previously58, and corpora lutea were collected from these ovaries.

The CL tissue samples were then immediately placed into a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube containing either 0.4 ml TRI Reagent® (Sigma–Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA, #T9424) or nothing, homogenized, and stored at −80 °C until processed appropriately for mRNA and protein analysis.

For immunohistochemistry, pieces of CL tissues were fixed in 4% (vol/vol) neutral formalin (pH 7.4) for 20–24 h and then embedded in paraffin.

Luteal steroidogenic cell isolation

The CLs at mid luteal stage were used for cell culture. Luteal tissue was enzymatically dissociated, and luteal cells were cultured as described previously59. Cell viability was greater than 85% as assessed by trypan blue exclusion. The cells in the suspension consisted of about 70% small LSCs, 20% large LSCs, 10% endothelial cells or fibrocytes, and no erythrocytes. In this study, these cells were defined as LSCs.

Changes in RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein expression levels throughout the estrous cycle and PGF-induced luteolysis in vivo

The expression of RIPK1 and RIPK3 mRNA and protein in the CL tissues of each stage (Early, Developing, Mid, Late and Regressed; each stage n = 4) and after PGF administration (0 h: control, 2 h, 4 h, and 12 h; each stage n = 4) were examined by quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting.

RIPKs protein localization in CL tissues throughout the estrous cycle (Early, Mid and Regressed; each stage n = 3) and after PGF administration (0 h: control, 4 h and 12 h; each stage n = 3) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry.

Local regulatory mechanisms of RIPK1 and RIPK3 expression in cultured LSCs

To clarify regulatory factors and the timing of changes of RIPK1 and RIPK3 expression in cultured mid LSCs, the cells were exposed to 2.3 nM recombinant human TNF (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and/or 2.5 nM recombinant bovine IFNG (kindly donated by Dr. S. Inumaru, NIAH, Ibaraki, Japan), 1.0 μM PGF (Sigma-Aldrich, #P7652) or 100 μM NONOate (a NO donor; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, #82150) for 12 and 24 h. The doses for treatments were selected based on previous reports7,8,11,13. After culture, the expression of RIPKs mRNA was determined by quantitative RT-PCR.

In addition, RIPKs protein expression was assessed by western blotting in cells treated with TNF and IFNG for 24 h, based on data from the first part of the experiment.

Effects of RIPKs on the function of cultured LSCs

To reveal the effects of Nec-1 on P4 production and cell death in LSCs, the cells were exposed to Nec-1 (50 μM; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., NY, USA, #BML-AP339-0100) with or without TNF and IFNG treatments for 12 or 24 h. The Nec-1 dose was selected based on previous reports60 and a preliminary study (data not shown). After 12 h of stimulation, the concentration of P4 in culture media and mRNA expression of BCL-2, BAX, CASP8, CASP3, RIPK1 and RIPK3 were determined by EIA and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. Furthermore, after 24 h of stimulation, cell viability and RIPKs protein expression were determined by AlamarBlue assay and western blotting, respectively.

Real time PCR

Real time PCR was performed with an ABI 7900 HT sequence detection system using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primer length (20–25 bp) and GC contents of each primer (50–60%) were synthesized (Supplementary Table 1). After a preliminary study, GAPDH was chosen as the best housekeeping gene. All primers were synthesized by Sigma (Custom Oligos, Sigma). Real time PCR was carried out as follows: initial denaturation (10 min at 95 °C), followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (15 s at 95 °C) and annealing (1 min at 60 °C). Data were analyzed using the method described by Zhao and Fernald61.

Western Blotting

Briefly, CL tissues or cultured LSCs were collected on ice in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, #R0258) in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Bazel, CHE, #11697498001). Each lysate was heated at 95 °C for 5 min and resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by transferred onto Immobilon-P Transfer Membrane (Millipore, MA, USA, #IPVH00010) in transfer buffer (0.3 mM Tris buffer, pH 10.4, 10% methanol; 25 mM Tris buffer, pH 10.4, 10% methanol; 25 mM Tris buffer, pH 9.4, 10% methanol, 40 mM glycine). After blocking in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T buffer (Tris-buffered saline, containing 0.1% Tween-20) for 1.5 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated overnight with rabbit polyclonal anti-RIPK1 or RIPK3 (dilution for both antibodies 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich, #SAB3500420; Sigma-Aldrich, #SAB2102009); or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (ACTB) antibody (dilution for antibody 1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, #A2228) at 4 °C. Subsequently, the membrane were incubated with secondary polyclonal anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (dilution 1:4000; for RIPK1 and RIPK3; Sigma-Aldrich, #A3812) or secondary anti-mouse IgG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (dilution 1:30,000) for ACTB (Sigma-Aldrich, #A3562) for 1.5 h at room temperature. After washing, immune complexes were visualized using the alkaline phosphatase visualization procedure. The intensity of the immunological reaction in the samples was estimated by measuring the optical density in the defined area by computerized densitometry using NIH Image (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Full length lanes of western blotting are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemistry

After dewaxing and washing, paraffin-embedded sections, cut at 4-μm thickness, were incubated at room temperature with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min to inactive endogenous peroxidase. Then, the sections were washed in PBS and incubated with normal goat serum for 60 min at room temperature followed by RIPK1 (1:400) or RIPK3 (1:200) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing twice, the sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Vector Laboratories, CA, USA, #PK-6200) for 60 min at room temperature. The reaction sites were visualized using a Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, #PK-6200) for 60 min at room temperature and an ImmPACT 3,30-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories, #SK-4100) for 5 min. The sections were counterstained for 2 min with hematoxylin. Positive immunohistochemistry staining was assessed as a characteristic brown staining, using a light microscope (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell viability

Viability of cells was determined by the AlamarBlue assay. Briefly, after culture, the culture medium was replaced with 100 μl D/F medium without phenol red, and 10 μl AlamarBlue® solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA, #DAL1100) was added. The cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The optical densities of the supernatants were read at 540 and 620 nm on a microplate reader, while fluorescence was measured in arbitrary fluorescent units following excitation at 530–560 nm and emission at 590 nm. In this assay, data were expressed as percentage of the appropriate control values.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and Graphic presentation of the data were done using GraphPad Software version 6, San Diego, USA. The results were considered significantly different when P < 0.05. The data are shown as the mean ± SEM of values obtained in separate experiments, each performed in quadruplicate.

In Experiment 1 (Figs 1 and 3), statistical analyses were performed using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

In preliminary in vitro studies (Experiments 2: Fig. 5A–D), statistical differences in RIPKs expression in LSCs on the gene level were examined using parametric one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (comparing the treatment group with the controls). Statistical differences in expression of RIPKs on the protein level in LSCs between controls and the TNF + IFNG treatment group (Experiment 2, Fig. 5E and F) were analyzed using Student’s t-test.

In Experiment 3 (Figs 6 and 7), differences in effects of Nec-1 on LSCs in the control and TNF + IFNG treatment groups were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA test followed by the Bonferroni comparison test.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hojo, T. et al. Programmed necrosis - a new mechanism of steroidogenic luteal cell death and elimination during luteolysis in cows. Sci. Rep. 6, 38211; doi: 10.1038/srep38211 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Hansel, W. & Blair, R. M. Bovine corpus luteum: a historic overview and implications for future research. Theriogenology 45, 1267–1294 (1996).

McCracken, J. A., Custer, E. E. & Lamsa, J. C. Luteolysis: a neuroendocrine-mediated event. Physiol Rev. 79, 263–323 (1999).

Juengel, J. L., Garverick, H. A., Johnson, A. L., Youngquist, R. S. & Smith, M. F. Apoptosis during luteal regression in cattle. Endocrinology 132, 249–254 (1993).

Rueda, B. R. et al. Increased bax and interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme messenger ribonucleic acid levels coincide with apoptosis in the bovine corpus luteum during structural regression. Biol Reprod. 56, 186–197 (1997).

Clarke, P. G. Developmental cell death: morphological diversity and multiple mechanisms. Anat Embryol (Berl). 181, 195–213 (1990).

Petroff, M. G., Petroff, B. K. & Pate, J. L. Mechanisms of cytokine-induced death of cultured bovine luteal cells. Reproduction 121, 753–760 (2001).

Taniguchi, H., Yokomizo, Y. & Okuda K. Fas-Fas ligand system mediates luteal cell death in bovine corpus luteum. Biol Reprod. 66, 754–759 (2002).

Korzekwa, A., Okuda, K., Woclawek-Potocka, I., Murakami, S. & Skarzynski, D. J. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis in bovine luteal cells. J Reprod Dev. 52, 353–361 (2006).

Friedman, A., Weiss, S., Levy, N. & Meidan, R. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha and its type I receptor in luteal regression: induction of programmed cell death in bovine corpus luteum-derived endothelial cells. Biol Reprod. 63, 1905–1912 (2000).

Hojo, T., Oda, A., Lee, S. H., Acosta, T. J. & Okuda, K. Effects of tumor necrosis factor α and Interferon γ on the viability and mRNA expression of TNF receptor type I in endothelial cells from the bovine corpus luteum. J Reprod Dev. 56, 515–519 (2010).

Okuda, K. et al. Progesterone is a suppressor of apoptosis in bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 71, 2065–2071 (2004).

Komiyama, J. et al. Cortisol is a suppressor of apoptosis in bovine corpus luteum. Biol Reprod. 78, 888–895 (2008).

Bowolaksono, A. et al. Anti-apoptotic roles of prostaglandin E2 and F2α in bovine luteal steroidogenic cells. Biol Reprod. 79, 310–317 (2008).

Nagata, S. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell 88, 355–365 (1997).

Antonsson, B. Bax and other pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family “killer-proteins” and their victim the mitochondrion. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 347–361 (2001).

Cohen, G. M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J. 326, 1 (1997).

Thornberry, N. A. & Lazebnik, Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science 281, 1312–1316 (1998).

Hitomi, J. et al. Identification of a molecular signaling network that regulates a cellular necrotic cell death pathway. Cell 135, 1311–1323 (2008).

Vandenabeele, P., Galluzzi, L., Vanden, Berghe, T. & Kroemer, G. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11, 700–714 (2010).

Festjens, N., Vanden, Berghe, T., Cornelis, S. & Vandenabeele, P. RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell’s decision to live or die. Cell Death Differ. 14, 400–410 (2007).

Degterev, A. et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 4, 313–321 (2008).

Declercq, W., Vanden, Berghe, T. & Vandenabeele, P. RIP kinases at the crossroads of cell death and survival. Cell 138, 229–232 (2009).

Cho, Y. S. et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 (2009).

He, S. et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-α. Cell 137, 1100–1111 (2009).

Zhang, D. W. et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 325, 332–336 (2009).

Holler, N. et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 1, 489–495 (2000).

Vanlangenakker, N., Vanden, B. T. & Vandenabeele, P. Many stimuli pull the necrotic trigger, an overview. Cell Death Differ. 19, 75–86 (2012).

Moujalled, D. M. et al. TNF can activate RIPK3 and cause programmed necrosis in the absence of RIPK1. Cell Death Dis. 4, e465 (2013).

Christofferson, D. E. & Yuan, J. Necroptosis as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 22, 263–268 (2010).

Oberst, A. et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471, 363–367 (2011).

Irmler, M. et al. Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature 388, 190–195 (1997).

Djerbi, M., Darreh-Shori, T., Zhivotovsky, B. & Grandien, A. Characterization of the human FLICE-inhibitory protein locus and comparison of the anti-apoptotic activity of four different flip isoforms. Scand J Immunol. 54, 180–189 (2001).

Weinlich, R., Dillon, C. P. & Green, D. R. Ripped to death. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 630–637 (2011).

Hojo, T. et al. Expression and localization of cFLIP, an anti-apoptotic factor, in the bovine corpus luteum. J Reprod Dev. 56, 230–235 (2010).

Okuda, K., Uenoyama, Y., Lee, K. W., Sakumoto, R. & Skarzynski, D. J. Progesterone stimulation by prostaglandin F2α involves the protein kinase C pathway in cultured bovine luteal cells. J Reprod Dev. 44, 79–84 (1998).

Skarzynski, D. J. & Okuda, K. Sensitivity of bovine corpora lutea to prostaglandin F2α is dependent on progesterone, oxytocin and prostaglandins. Biol Reprod. 60, 1292–1298 (1999).

Korzekwa, A. J., Jaroszewski, J. J., Woclawek-Potocka, I., Bah, M. M. & Skarzynski, D. J. Luteolytic effect of prostaglandin F2α on bovine corpus luteum depends on cell composition and contact. Reprod Domest Anim. 43, 464–472 (2008).

Skarzynski, D. J. et al. Growth and regression in bovine corpora lutea: regulation by local survival and death pathways. Reprod Domest Anim. 48 Suppl 1, 25–37 (2013).

Skarzynski, D. J. et al. Administration of a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor counteracts prostaglandin F2-induced luteolysis in cattle. Biol Reprod. 68, 1674–1681 (2003).

Shirasuna, K. et al. Prostaglandin F2α increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the periphery of the bovine corpus luteum: the possible regulation of blood flow at an early stage of luteolysis. Reproduction. 135, 527–539 (2008).

Kim, Y. M., Talanian, R. V. & Billiar, T. R. Nitric oxide inhibits apoptosis by preventing increases in caspase-3-like activity via two distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 272, 31138–31148 (1997).

Melino, G. et al. S-nitrosylation regulates apoptosis. Nature 388, 432–433 (1997).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Nitric oxide prevents tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced rat hepatocyte apoptosis by the interruption of mitochondrial apoptotic signaling through S-nitrosylation of caspase-8. Hepatology 32, 770–778 (2000).

Penny, L. A. et al. Immune cells and cytokine production in the bovine corpus luteum throughout the oestrous cycle and after induced luteolysis. J Reprod Fertil. 115, 87–96 (1999).

Pate, J. L. & Landis Keyes, P. Immune cells in the corpus luteum: friends or foes? Reproduction 122, 665–676 (2001).

Petroff, M. G., Petroff, B. K. & Pate, J. L. Expression of cytokine messenger ribonucleic acids in the bovine corpus luteum. Endocrinology 140, 1018–1021 (1999).

Robinson, N. et al. Type I interferon induces necroptosis in macrophages during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Nat Immunol. 13, 954–962 (2012).

Du, Q., Xie, J., Kim, H. J. & Ma, X. Type I interferon: the mediator of bacterial infection-induced necroptosis. Cell Mol Immunol. 10, 4–6 (2013).

Zhang, F., zur, Hausen, A., Hoffmann, R., Grewe, M. & Decker, K. Rat liver macrophages express the 55 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor: modulation by interferon-γ, lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor-α. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 375, 249–254 (1994).

Bebo, B. F. Jr. & Linthicum, D. S. Expression of mRNA for 55-kDa and 75-kDa tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors in mouse cerebrovascular endothelium: effects of interleukin-1β, interferon-γ and TNF-α on cultured cells. J Neuroimmunol. 62, 161–167 (1995).

Sugino, N. & Okuda, K. Species-related differences in the mechanism of apoptosis during structural luteolysis. J Reprod Dev. 53, 977–986 (2007).

Tilly, J. L. Apoptosis and ovarian function. Rev Reprod. 1, 162–172 (1996).

Matsubara, H. et al. Gonadotropins and cytokines affect luteal function through control of apoptosis in human luteinized granulosa cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 8, 1620–1626 (2000).

Rueda, B. R. et al. Decreased progesterone levels and progesterone receptor antagonists promote apoptotic cell death in bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 62, 269–276 (2000).

Sun, L. et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227 (2012).

Kearney, C. J., Cullen, S. P., Clancy, D. & Martin, S. J. RIPK1 can function as an inhibitor rather than an initiator of RIPK3-dependent necroptosis. FEBS J. 281, 4921–4934 (2014).

Miyamoto, Y., Skarzynski, D. J. & Okuda, K. Is tumor necrosis factor alpha a trigger for the initiation of endometrial prostaglandin F2α release at luteolysis in cattle? Biol Reprod. 62, 1109–1115 (2000).

Skarzynski, D. J. et al. In vitro assessment of progesterone and prostaglandin e(2) production by the corpus luteum in cattle following pharmacological synchronization of estrus. J Reprod Dev. 55, 170–176 (2009).

Okuda, K., Miyamoto, A., Sauerwein, H., Schweigert, F. J. & Schams, D. Evidence for oxytocin receptors in cultured bovine luteal cells. Biol Reprod. 46, 1001–1006 (1992).

Xu, X. et al. Necrostatin-1 protects against glutamate-induced glutathione depletion and caspase-independent cell death in HT-22 cells. J Neurochem. 103, 2004–2014 (2007).

Zhao, H. & Fernald, R. D. Comprehensive algorithm for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Comput Biol. 12, 1045–1062 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd., Osaka, Japan, for recombinant human TNF (HF-13) and Dr. S Inumaru of the NIAH, Ibaraki, Japan, for recombinant bovine IFNG. This work was supported by grants of the National Science Center in Poland (2013/11/D/NZ9/02685). KO was supported by the Research Program on Innovative Technologies for Animal Breeding, Reproduction, and Vaccine Development (REP-1002) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan. The article processing charge was covered by the KNOW project: “Healthy Animal - Safe Food”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. designed the experiments; T.H., K.K.P.-T. and A.W.J. performed the experiments; T.H., K.L. and D.J.S. analyzed the results; and T.H., M.J.S., K.O. and D.J.S. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hojo, T., Siemieniuch, M., Lukasik, K. et al. Programmed necrosis - a new mechanism of steroidogenic luteal cell death and elimination during luteolysis in cows. Sci Rep 6, 38211 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38211

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38211

This article is cited by

-

Diverse actions of sirtuin-1 on ovulatory genes and cell death pathways in human granulosa cells

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2022)

-

The role of oxidative stress in ovarian aging: a review

Journal of Ovarian Research (2022)

-

Premature ovarian insufficiency: pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell

Journal of Molecular Medicine (2021)

-

Necroptosis in stressed ovary

Journal of Biomedical Science (2019)

-

Effects of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) on cell-death pathways in the bovine corpus luteum (CL)

BMC Veterinary Research (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.