Abstract

Time crystals represent temporal analogues of the spatial self-ordering exhibited by atomic or molecular building blocks of solid-state crystals. The pursuit of discrete time crystals (DTCs) in periodically forced Floquet closed systems has revealed how they can evade thermalization and loss of temporal order. Recently, it has been shown that even with coupling to the ambient and its concomitant noise, some states maintain their time crystalline order, forming dissipative DTCs. Here, we introduce a scheme for the realization and state control of dissipative DTCs hinging on pumping a Kerr optical resonator with a phase-modulated continuous-wave laser. We show the possible symmetry breaking states possess temporal long-range order and analyze the phase noise of the accompanying signature radio frequency (RF) subharmonic. Besides offering a technique for generating high-spectral-purity RF signals, this versatile platform empowers controlled switching between various DTC states through accessible experimental knobs, hence facilitating the future study of DTC phase transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time crystals embody spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) in the temporal domain, paralleling the fundamental symmetry violations underlying the formation of solid state crystals by atomic or molecular building blocks1. Crystallinity in time, initially proposed in 20122, in a sense extends the equitable treatment of time and space and fits well in the timeline of our understanding of these two physical quantities; believed originally to be absolute, time was shown in early 20th century to be relative, like space, and hence came to be understood in the context of “spacetime”3. On the other hand, following Landau’s classification of matter predicated on symmetry, time crystals are now being studied as a new state of matter, of which there is still much to be discovered.

The Hamiltonian describing the formation of a typical condensed-matter crystal possesses continuous space-translation symmetry1. Furthermore, such a spatial crystal emerges in an undriven system. In contrast, spontaneous time-translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) was proved impossible in thermal equilibrium4,5,6. Periodic forcing, on the other hand, defines a discrete temporal symmetry. The spontaneous breaking of this symmetry by a physical quantity can realize an n-tupling discrete time crystal (n-DTC) when the periodicity of the said observable (the response) differs from and is an integer multiple n > 1 of that of the drive1,7. The pursuit of DTCs has thus far focused predominantly on closed systems, where coupling to the environment is vanishingly small. This research endeavor has proven rewarding by divulging how some driven systems find creative ways to postpone, or sometimes even altogether defy, thermalization, the heat death and loss of crystalline order naturally expected of a driven system with negligible outflow of energy1,7.

Researchers have more recently ventured toward time crystallinity under dissipation and noise8,9,10. The study of dissipative DTCs can bear fruit through identifying certain operation regimes or uncovering dissipation engineering techniques to exploit loss as a resource rather than a nuisance11. It also offers practical significance, because perfect isolation of real-world systems from the environment is never possible. Besides theoretical progress, which has shown that certain DTC systems can survive the noise concomitant with external coupling, very recent experiments have demonstrated dissipative DTCs in two distinctly different platforms, namely, a Kerr-nonlinear optical resonator pumped by two independent continuous wave (CW) lasers12, and a driven Bose–Einstein condensate of rubidium atoms in a cavity13. These experiments hold great promise for further examinations of dissipative DTC properties. It should be mentioned that classical dissipative periodically driven systems can form classical DTCs14,15.

Here, we introduce another scheme for the realization and state control of photonic dissipative DTCs based on pumping a Kerr optical resonator with a phase-modulated CW laser in which the modulation frequency equals an integer multiple M > 1 of the cavity free spectral range (FSR) (see Fig. 1a). We present a study of the general case of pump phase modulation at an integer multiple of the pulse repetition rate, particularly from the perspective of TTSB and DTCs. We derive a generic mean-field formulation for M ≥ 1 and investigate its stable and unstable equilibria using the method of moments. Treating solitons as particles16 in an externally induced potential, this approach demonstrates the rigidity and temporal long-range order of the realizable DTC states. The analysis shows that the number of stable equilibria in the parametrically seeded system equals M + 1, in which the lowest- and highest-energy states do not demonstrate discrete TTSB. Therefore, only for M > 1 can DTCs emerge. We also analyze the phase noise of the accompanying signature radio frequency (RF) subharmonic signal created when DTCs form and highlight the feasibility of reducing it with respect to the modulating oscillator. Our results reveal the possibility of realizing different n-DTC states and switching between them in a controlled manner through tweaking experimentally available knobs. Apart from introducing a versatile photonic DTC platform, this approach can be utilized to build robust, compact, and lightweight low-phase-noise RF and microwave photonic sources through the monolithic integration of the modulator and Kerr resonator using emerging materials such as lithium niobate17,18,19.

a Schematic showing a typical ring resonator side-coupled to an access waveguide. Modulation of the continuous-wave (CW) laser pump at an integer multiple of the resonator free spectral range (here for ωM = 4D1), creates sidebands for the laser tone (blue spikes with filled circle tips on the left). This drive creates a broader array of phase-locked frequency harmonics in the cavity, corresponding to a train of temporal solitons. For certain arrangements, these solitons break the discrete time-translation symmetry defined by the drive periodicity (here one-fourth the round-trip time, TR/4), realizing a DTC with signature subharmonics (red spikes with filled diamond tips seen on the right). b–d The intra-cavity waveform without solitons (b), and with 1 and 2 soliton peaks, giving rise to a 4-DTC (c) and a 2-DTC (d). The spectrum in a with harmonics filling all free spectral ranges between drive sidebands (red spikes between dotted blue ones) is the frequency spectrum of the waveform depicted in c. To better visualize the background modulation induced by pump phase modulation, vertical axis data in (b) is limited to (0.5, 1) in normalized units. This modulation is small (≈10 times) compared to the soliton peak power and hence hardly visible in c, d.

Results and discussion

Model and system symmetry

If the CW laser driving a Kerr resonator is phase-modulated at frequency ωM, sidebands will be generated symmetrically with respect to this pump. Depending on ωM/D1, the ratio of the modulation frequency to cavity FSR, and δM, the modulation depth or intensity, modulation-induced sidebands will have different effects on the frequency comb generation process. It has been shown that seeding microresonator-based Kerr comb (microcomb) generation20 by a modulated CW laser can improve comb stability21,22 and deterministically create a train of temporal dissipative Kerr solitons23,24,25,26,27,28. Pump modulation at the cavity FSR (M = 1) with a stable “clock” can enhance the long-term stability of the microcomb and improve the spectral purity and phase noise of the microwave signal22,23. Additionally, modulation depth provides added control over the beatnote signal power while system dynamics and attractors are different from those in a cavity pumped by a free-running laser.

In the current study, we focus on the case of the modulation frequency being an integer multiple M > 1 of the FSR, i.e., ωM = MD1. In this notation, ωM is an angular frequency in rad/s and D1/2π = 1/TR denotes the FSR in Hz and the reciprocal of the round-trip time TR29,30. Similar to DTC formation in a dichromatically pumped Kerr cavity12,31,32,33, drive periodicity defines a discrete temporal symmetry exhibited in the modulation of the intra-cavity CW background (Fig. 1b), while the spontaneous appearance of one or more temporal dissipative solitons imprints a larger time period upon the system output (Fig. 1c, d). Therefore, at any fixed position on the output waveform path, photon count probability will demonstrate a periodicity that is an integer multiple of that of the same observable monitored before the resonator. As a result, discrete TTSB accompanied by characteristic subharmonic generation in the frequency domain, occurs.

The time-domain description of the system in the laboratory reference frame takes the form

where the complex waveform A(t, θ) is normalized such that ∫2π∣A∣2 dθ renders the number of intra-cavity photons, κ denotes the power decay rate, κc is the coupling coefficient, \(\sigma ={{\Omega }}-{\omega }_{{j}_{0}}\) indicates the detuning between the CW laser and pumped resonance frequencies Ω and \({\omega }_{{j}_{0}}\), Dm for 1 ≤ m ≤ N are dispersion coefficients (m and N both integers), θ is the azimuthal angle around the resonator, related to the fast time τ via θ = 2πτ/TR (modulo 2π), g is the four-wave mixing (FWM) gain or nonlinear coupling coefficient, and F0 represents the laser pump power17,20 (see the “Methods” section). Equation (1) is invariant under t → t + 2π/ωM or θ → θ + 2π/M (equivalently, τ → τ + 2π/ωM), and therefore possesses time-translation symmetry defined by the drive. Soliton formation can cause discrete TTSB and DTC formation for M > 1, because the drive is periodic by TDrive = 2π/ωM = TR/M while the pulse train exiting the resonator has a larger periodicity TResponse = nTDrive, the integer n satisfying 1 < n ≤ M.

Equation (1) can readily be recast by the change of variable θ → θ−ωMt/M, equivalent to transitioning to a reference frame rotating with angular velocity ωM/M. The resulting equation is better conducive to numerical modeling and upon normalization reads

The field envelope ψ = A*/Ath and external pump amplitude \({f}_{0}=\left[\sqrt{{\kappa }_{{{{{{{{\rm{c}}}}}}}}}}/(\kappa /2)\right]\,{F}_{0}^{* }/{A}_{{{{{{{{\rm{th}}}}}}}}}\) have been normalized with respect to the modulus of the comb generation threshold \(| {A}_{{{{{{{{\rm{th}}}}}}}}}| =\sqrt{\kappa /(2g)}\)34; note the complex conjugation in going from Eq. (1) to Eq. (2)35. The slow time \(\bar{t}=t/(2{t}_{{{{{{{{\rm{ph}}}}}}}}})\) has been normalized by twice the pumped resonance photon life-time tph = κ−1, while detuning α = −2σ/κ and dispersion coefficients dm = −2Dm/κ have been re-scaled through division by the pumped mode half-width at half-maximum (HWHM). We will base our subsequent numerical modeling and stability analysis using the split-step Fourier transform method in Eq. (2), which is a damped and driven nonlinear Schrödinger or a modified Lugiato–Lefever equation (NLSE or LLE, respectively)36. In the context of Bose–Einstein condensates, the NLSE is often called the Gross–Pitaevskii equation. The split-step Fourier transform method has been shown to offer excellent accuracy in modeling Kerr microcomb and fiber cavity soliton systems, and to agree well with experiments29,35,37.

Before proceeding, we estimate parameters of a resonator suitable for the demonstration of the proposed phenomena. Consider a whispering gallery mode (WGM) resonator made out of magnesium fluoride (MgF2), interrogated with a 1.5 μm laser. Accounting for geometrical and material dispersion, a resonator with a 10 GHz FSR is characterized with the dispersion parameter \({D}_{2}={\omega }_{{j}_{0}+1}+{\omega }_{{j}_{0}-1}-2{\omega }_{{j}_{0}}\approx 0.7\) kHz. With a HWHM modal linewidth of 150 kHz, this translates into d2 = −5 × 10−3, and comb generation power threshold falls in the few mW range. Loading of the cavity can be modified by a few orders of magnitude through controlling the gap between the evanescent field coupler and the resonator surface as well as by changing the coupling element material (the prism coupler). Besides MgF2, fused silica or another transparent optical material can be utilized. These estimations show that the experiments proposed here can be readily achieved in practice. Additionally, pump modulation at the FSR frequency (M = 1) for MgF2 resonators with FSRs as low as 12 and 14 GHz have been reported in recent years22,25. Subharmonic generation, one of the criteria for DTCs, can in principle be realized also in normal dispersion32,38.

DTC waveforms

Two sets of examples are shown in Fig. 2 in a resonator with d2 = −6.3 × 10−3 (anomalous dispersion), pump intensity f0 = 1.275 and pump-resonance detuning α = 2 (red detuned), modulation frequency ωM = 4D1 (i.e., M = 4), and two different modulation depths δM = 0.7 (Fig. 2a–d) and δM = 0.3 (Fig. 2e–h). The latter case of δM = 0.3 corresponds to the same set of numerical values also used in producing Fig. 1b–d. It is clear that without soliton formation, the temporal waveform leaving the resonator is periodic with TDrive = TR/4 (see Fig. 2c, d and g, h). However, when either one or three solitons are trapped in the lattice created by pump modulation, the periodicity of the soliton train changes to TResponse = TR = 4TDrive, thereby realizing 4-DTCs. The examples shown in Fig. 1d corresponds to the case of TResponse = TR/2 = 2TDrive. If four pulses emerge and all lattice spots per round-trip time are occupied with soliton peaks the discrete symmetry of the system will be respected and TTSB will not happen. With larger M, other DTC sizes (response to drive ratios) are possible. For instance, using the same parameters at δM = 0.7, we observed discrete TTSB with M up to 19. The pulses emerge from a random high-energy initial state (i.e., through hard excitation39) and propagate stably for as long as the drive is on; the integration time in our numerical simulations have been hundreds of cavity photon lifetimes.

Symmetry breaking and period multiplication in an optical resonator pumped by a phase-modulated continuous-wave laser, where ωM = 4D1. Two different modulation depths are considered, δM = 0.7 in a–d and δM = 0.3 in e–h. a One soliton per round-trip time emerges, resulting in discrete time-translation symmetry breaking and a 4-tupling discrete time crystal (4-DTC). b The frequency spectrum of a, where the stronger modulation-induced frequency tones near the central pump harmonic are 4 free spectral ranges apart and soliton subharmonics fill in the modes between them. c, d Same as a, b, but without soliton excitation. e–h Same as a–d, respectively, but for the smaller modulation depth of 0.3. In e, f 3 soliton peaks emerge per round-trip time, but again a 4-DTC is realized. Note the different scales on the vertical axes in panels (a, e) compared to c, g. The insets in b, f show the frequency spectra in the immediate vicinity of the continuous-wave pump. Numerical values of integration parameters are stated in the text.

As the modulation frequency is increased successively, lattice sites created on the modulated CW background will be more packed and shorter pulses ought to be generated. While solitons tend to become shorter through increasing the pump-resonance detuning, packing more solitons in one round-trip naturally translates into a need for cavity dispersion engineering to reduced the magnitude of D240. Furthermore, from an experimental perspective, faster modulators will be required. As low-Vπ commercial modulator frequencies are currently bound to tens of GHz (typically below 100 GHz), demonstration of large dissipative DTCs in this system requires resorting to longer resonators. Increasing the resonator size in WGM crystalline resonators entails competing with overmodedness41 and avoided mode crossings42 which are known to challenge soliton formation. This issue can be more easily addressed in integrated platforms17 where racetrack resonators or those with wedge-shaped rims have been shown to support repetition rates down to a few GHz43. We have shown elsewhere that pumping with two independent lasers can also create dissipative DTCs without suffering from the constraints of off-the-shelf high-frequency modulators12. While integrated, fast, and low-Vπ opto-electronic modulators are being developed in the integrated photonics community44, the principles developed here can also apply to fiber resonators24, where the cavity round-trip time is much longer (typically 3–4 orders of magnitude) compared to microresonators.

Stability analysis

What is the relationship between the modulation frequency and the number and temporal separation of stable solitons leaving the resonator per round-trip time? Using the method of moments and in analogy with the notion of particle momentum in quantum mechanics, a formalism revealing the force exerted by pump phase modulation on dissipative solitons and the potential trapping them can be developed, as detailed in the “Methods” section. The equation of motion for the waveform momentum \({{{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}}}}\) is \({{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}}{{{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}}}}/{{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}}\bar{t}=-2{{{{{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}}}}+{{{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}}}}\), in which pulse and modulation parameters determine the force \({{{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}}}}\)31. For modulation depth δM of order unity, this force will vanish at fixed points \({\theta }_{k}^{* }=(2k+1)\pi /(2M)\), with integer k. The potential, on the other hand, will assume the form \({{{{{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}}}}(\theta )=-a\sin (M\theta )+b\), where a and b are constants (see the “Methods” section). Hence, the potential is essentially the phase modulation profile with a negative sign, \(-\sin (M\theta )\), plus a constant offset not affecting stability. Potential minima (half of the fixed points) are the stable equilibria of the system.

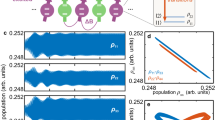

These predictions are substantiated by the numerical integration of Eq. (2); at steady state, the soliton peaks always settle at the potential profile minima, as seen in Fig. 3a. The soliton peaks in Fig. 3a illustrate the final state of the pulse train in Fig. 3b, where Eq. (2) has been integrated with a random high-energy initial state and at ωM = MD1, leading to the appearance of multiple peaks, all of which are dragged to the stable equilibria. Non-ideal locking of the modulation frequency to the pumped FSR has been assumed in Fig. 3c by considering (ωM/M−D1) to be a noisy signal with a uniform distribution of zero mean and 2% HWHM standard deviation. As the plot shows, it may take longer for the solitons to merge, but the steady state remains settling to the potential minima. Also, with sudden large-enough disruptions of the pump conditions, other soliton peaks may appear in the cavity, but they will converge under the drag imposed by the modulation, again to the expected stable states (see Fig. 4). Note that in the final states in Figs. 3 and 4, discrete TTSB does not occur (both the drive and response have the same periodicity of TR/4).

a Steady-state pulse train waveform per round-trip time (left axis, solid blue) and the modulation-induced potential profile (right axis, dashed orange). The soliton peaks settle in the potential minima as predicted by the theoretical model. b Temporal evolution of the soliton peaks emerging from an energetic random initial waveform whose steady state is plotted in a. Multiple solitons form in the cavity and converge under the drag of the modulation potential. Numerical parameters used in a, b are α = 2.1, ωM = 4D1, d2 = −5 × 10−3, dm = 0 (m ≥ 3), f0 = 1.35, and δM = 0.4. c Same as b but for non-ideal locking of the modulation frequency to 4D1; ωM/4−D1 is taken to be a noisy signal of uniform distribution with zero mean, 2% half width at half-maximum standard deviation, and temporal fluctuations on the order of the integration step (\(\bar{t}/400\)).

Convergence and merging of solitons with strong pump power disruptions. The evolution of the pulse train (a) and its spectrum (b) in the cavity show that the initial state consisted of 2 solitons per round-trip time (a 2-DTC, ωM = 4D1). The power change profile (red dotted curve) and intra-cavity energy (black solid) are plotted in c. Power change increases the intra-cavity energy and more solitons form, all converging to the stable equilibria enforced by the pump modulation (M = 4). The final state constitutes 4 solitons per round-trip time, one in each potential minimum. The initial (bright blue) and final (red) waveforms and comb spectra are depicted on top in a and b. Parameter values are the same as those in Fig. 3.

Absence of DTCs for M = 1

Before proceeding to state control, we digress briefly to emphasize the significance of the foregoing analysis. Besides underpinning temporal long-range order in the proposed DTCs, this analysis highlights the central role of phase modulation at an integer multiple of the FSR in the realization of discrete TTSB in this platform. Without modulating the pump, photon detection probability in the microcomb drive possesses continuous time-translation symmetry and cannot demonstrate DTCs12. However, when the modulation frequency matches the FSR (M = 1), the framework presented above illustrates the existence of two stable equilibria in the system, one with no solitons and the other with one soliton per round-trip time23,26. Therefore, the drive introduces a discrete temporal symmetry which is not violated by soliton formation in steady state; even if multiple pulse peaks emerge initially, only one may ultimately survive such that response periodicity equals TR both with or without soliton generation23. Finally, when the pump is modulated at a frequency that is a larger-than-unity integer multiple of the FSR (M > 1), the discrete symmetry introduced by the drive can be violated through some distributions of soliton peaks over potential lattice sites to create DTCs. This dichotomy is well manifested in the intra-cavity energy ∫2π∣ψ∣2 dθ versus detuning curves of Fig. 5. In this region, corresponding to normalized detuning roughly between 3 and 8 for the considered parameters in this example, each step of higher energy indicates a stable state with one soliton peak more per round-trip time than the adjacent lower-energy one, whereas the lowest-energy step signifies soliton-free states. In the absence of modulation, different numbers of solitons can be realized per round-trip time and the relative temporal delay between them is not dictated by the pump29 (Fig. 5a). With modulation at an integer multiple of the FSR, ωM = MD1, a discrete time-translation symmetry is defined by the drive and the maximum number of soliton peaks as well as their relative time delay becomes constrained by M. For M > 1, TTSB is possible, as seen in Fig. 5b, where M = 4 and frequency comb states lying on middle steps (i.e., steps other than the lowest- and highest-energy) correspond to DTCs (cf. Fig 2a, e). In contrast, only two steady states are possible when M = 1 (i.e., there is no middle step between the top and bottom ones) and neither of the pertinent waveforms leads to TTSB (see Fig. 5c). DTCs can thus not form when ωM = D1.

Intra-cavity energy versus detuning α curves for microcombs without (a) and with b, c pump modulation. System parameters are d2 = − 2 × 10−2, dm = 0 (m ≥ 3), and f0 = 2.5; in b, c δM = 0.75. In the step-like profiles when 3 < α < 8, each step of higher energy indicates a stable state with one soliton peak more per round-trip time than the adjacent lower-energy one. The lowest-energy step signifies soliton-free states. a In the absence of modulation, different numbers of solitons can emerge per round-trip time and the relative temporal delay between them is not dictated by the pump. b, c With modulation at an integer multiple of the FSR, a discrete time-translation symmetry is defined by the drive and the maximum number of soliton peaks as well as their relative time delay becomes constrained by M = ωM/D1. b For M > 1, time-translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) is possible. The plot shows the case of M = 4 where frequency comb states lying on middle steps (i.e., steps other than the lowest- and highest-energy ones in the plot) correspond to discrete time crystals (DTCs) (cf. Fig. 2a, e). (c) When M = 1, neither of the possible states leads to TTSB (there is no middle step). Therefore, DTCs cannot form when ωM = D1. Intra-cavity energy has been normalized to ∣f0∣2 in all panels.

DTC generation and controlled phase switching

As the multistability embodied in the soliton steps in Fig. 5 signifies, the number of solitons per round-trip time forming spontaneously in the cavity cannot be accurately controlled. Based on the understanding furnished by the foregoing analysis, one can devise ways to realize desirable DTC states in a controlled manner. Two example scenarios are illustrated in Fig. 6, where ωM = 4D1. In Fig. 6a–c, the initial state is a 4-DTC. The modulation is shortly turned off and then back on, now at ωM = 2D1; see the modulation profile in Fig. 6c, at which stage the solitons are dragged towards the stable equilibria of the new phase-modulated system and the two previously centered at θ1 = π/8 and θ2 = 5π/8 merge into one. This procedure realizes a 2-DTC when the modulation frequency goes back to ωM = 4D1. The waveforms and frequency spectra of the initial (blue) and final (red) DTC states are plotted in Fig. 7a, b. Panels d–f of Fig. 6 depict another example for transitioning from a 2-DTC to another 4-DTC (this time one with one soliton per round-trip time). To achieve this, the modulation frequency is changed to ωM = D1, again resulting in the merging of the pulses into one before it resumes the original value of ωM = 4D1. Figure 7 shows the waveforms (c) and frequency spectra (d) of the initial (blue) and final (red) DTC states.

Controlled switching between discrete time crystal (DTC) states is possible in a Kerr microresonator driven by a phase-modulated pump through changing the modulation frequency. Two scenarios of switching from a 4-DTC to a 2-DTC (a–c), and from a 2-DTC to another 4-DTC (d–f) are depicted. Panels a, d illustrate the temporal evolution of the pulse trains while (b, e) show their frequency spectra. The intra-cavity energy and modulation depth and frequency are shown in c, f. Pump detuning is fixed throughout the process. Numerical parameters are α = 2, d2 = −8 × 10−3, dm = 0 (m ≥ 3), and δM = 0.4, and f0 = 1.35.

It should be stressed that for a system to host DTCs, first it ought to possess discrete time translation symmetry. This symmetry is absent in monochromatically driven Kerr microcombs, even in the presence of the 3rd- and higher-order dispersion or avoided mode crossings; this has been discussed in detail elsewhere12. As a result, dispersive wave emission and soliton crystals in CW-pumped Kerr microresonators do not constitute DTCs. We note, however, that if effects such as higher-order dispersion or Raman-induced frequency shift change the repetition rate with respect to the FSR, the modulation frequency in the current DTC generation scheme can readily be adjusted to compensate for soliton recoil and dominate the dynamics, and this effect is well captured by Eq. (2). An example is depicted in Fig. 8. Non-negligible D3 can create dispersive waves on one side of the pump and cause soliton recoil to the opposite side40,45. Therefore, the soliton train will start moving in the rotating reference frame of Eq. (2), such that it will generally be more difficult to trap and merge solitons with ωM = MD1 (see Fig. 8a–c), where all parameters are the same as those in Fig. 6 except for a non-zero third-order dispersion coefficient. Phase modulation tends to reduce the temporal separation of the solitons when they are in the vicinity of a potential minimum but increase it as one of the pulses drifts away to a neighboring one, as observed in Fig. 8a. The successive increase and decrease of temporal separations, and the accompanying changes of soliton interaction energy, imprints a periodic modulation on the intra-cavity energy, seen in the region marked by ωM = 2FSR in Fig. 8c. The repetition rate shift can be offset by adjusting the modulation frequency: if the soliton spectral center moves from the pumped mode j0 to j0 + ηr, the repetition rate varies by ΔD1 ≈ ηrD2 and modifying the modulation frequency accordingly will balance soliton recoil, as illustrated in Fig. 8d–f.

Compensation of soliton recoil by adjusting the modulation frequency. All numerical parameters are the same as those in Fig. 6, except for the non-zero third-order dispersion coefficient d3 = −1.6 × 10−4. Dispersive wave emission shifts the soliton spectral center (soliton recoil), changing the pulse repetition rate and resulting in the drift of the pulse train in the rotating reference frame. a–c At ωM = MD1, the potential lattice is no longer stationary with respect to the soliton train, so that the same modulation depth (as when d3 = 0) cannot create state switching. The relative motion of the modulation-induced lattice and pulse train modulates the soliton interaction energy, as seen in c. d–f By adjusting the modulation frequency to compensate for the soliton recoil (here ηr = 2), it is possible to offset the effect of higher-order dispersion completely and effectuate discrete time crystal (DTC) state switching as before (cf. Fig. 6a–c). The final soliton train and its spectrum are plotted on top of panels (d) and (e), respectively, with the black arrow pointing at the dispersive wave. a, d Temporal evolution of the pulse trains; b, e Frequency comb spectra; c, f Intra-cavity energy (bottom axes) and modulation depth (top axes). In c, f, FSR stands for free spectral range.

In the state control approach resulting in Figs. 6–8, we have interjected intervals of no modulation between those with different modulation frequencies because the formulation presented herein assumes integer M. Although this step can be implemented experimentally, it is nonetheless not necessary and a continuous sweep of the modulation frequency is expected to produce the same effect. Adiabatic increase of the modulation frequency while preserving the number of solitons (e.g., one soliton per round-trip time) can transition the system through various DTC phases (e.g., successive single-soliton n-DTCs). Yet, as this procedure constitutes new TTSB states while altering the symmetry of the underlying system, it does not accurately parallel phase transitions in the context of condensed matter crystals where new phases under the same symmetry are studied.

It has been shown that the number of solitons in a CW-pumped Kerr cavity can be controlled by the forward or backward sweep of the pump-resonance detuning29,46. Through the prudent choice of the sweeping rate, direction, and final detuning, this procedure can alter the number of solitons per round-trip time and in principle guarantee achieving any number of them, thereby enabling DTC state control. Moreover, driving the microresonator by two pulse trains27 with judiciously chosen repetition rates and relative delays can effectuate switching between different DTC states when one pulse train locks a subset of the microcomb solitons while the other tweezes the rest through changing the delay24. In both cases of detuning sweep or driving by delayed pulse trains, the modulation can adiabatically be turned off prior to state switching and then back on (as in Figs. 6–8).

Phase noise reduction of the RF beatnote

Analysis of DTC stability in the current system naturally connects to the notion of subharmonic phase noise. Therefore, we consider here the phase noise of the generated subharmonic and how it relates to that of the oscillator driving the modulator and a Kerr microcomb driven by a free-running laser.

Oscillator phase noise reduction by frequency division is frequently used to generate RF and microwave signals of high spectral purity from an optical frequency comb47,48. The comb should first be stabilized by optical means, e.g., two-point locking or f−2f self-referencing accompanied with single-point locking to an external reference. The phase noise of the lasers utilized for comb stabilization is often much higher than standard high-quality RF sources. In contrast, the phase noise of the photonic RF signal demodulated on a fast photodiode can be better than high-quality RF sources. This improvement is achieved through frequency division.

Generally, when a frequency f0 = 〈f0〉 + Δf0 characterized with an average value 〈f0〉 and random fluctuations Δf0(t) is divided by n, fluctuations of the smaller frequency fRF = f0/n is also reduced by the same factor to ΔfRF(t) = Δf0(t)/n. It can readily be shown that the power spectral density of the two signals will be related through \({S}_{{{\Delta }}{f}_{{{{{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}}}}}}={S}_{{{\Delta }}{f}_{0}}/{n}^{2}\). Therefore, the phase noise \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}}_{{\phi }_{{{{{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}}}}}}={S}_{{{\Delta }}{f}_{{{{{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}}}}}}/(2{f}^{2})\) of the divided frequency will also drop as n2. In this expression f is the offset from the average frequency and the power spectral densities \({S}_{{{\Delta }}{f}_{0}}\) and \({S}_{{{\Delta }}{f}_{{{{{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}}}}}}\) indicate the random fluctuations of frequency rather than phase49,50.

In view of the crucial role of subharmonic generation in DTC formation, TTSB in the platform discussed herein is naturally accompanied with phase noise reduction. A prominent feature of optical DTCs predicated on a pump-modulated or dichromatically pumped Kerr microcomb is indeed the possibility of decreasing the phase noise of the RF beatnote in comparison with the drive phase noise. We have recently reported this effect in DTCs in a dually pumped Kerr microcomb12,51, where the subharmonic phase noise is reduced compared with the beatnote of the two driving lasers. In pump-modulated Kerr microcomb DTCs, subharmonic phase noise is reduced with respect to the signal modulating the laser. In both cases, the reduction factor is n2, the DTC size squared.

In addition to the phase noise reduction due to frequency division, formation of DTCs in a parametrically seeded microcomb results in lowering the fundamental phase noise associated with Kerr frequency comb generation. Solitons in a Kerr comb pumped by a free-running laser experience random walk and the associated phase noise of the RF signal displays an f−2 dependence50—the noise increases without limit at small frequency offsets, hinting at the unbound soliton timing jitter in the cavity52. Subdued by modulation, this jitter in soliton arrival time can be constrained in a pump-modulated comb. The phase diffusion is suppressed and the phase noise gains an \({({f}^{2}+{\kappa }_{{{{{{{{\rm{Loop}}}}}}}}}^{2})}^{-1}\) dependence instead, where the nonzero relaxation factor κLoop is the locking loop bandwidth, which depends on the parameters of the modulated light, duration of the pulse, and finesse of the optical cavity. Owing to this coefficient, the DTC subharmonic phase noise can be smaller than the fundamental quantum noise of a free-running Kerr comb photonic oscillator at small offsets.

To better understand this phenomenon, we introduce the following expression, based on the theory of injection-locked oscillators and phase-locked loops53,54. The phase noise of the slave oscillator (here, the DTC) improves when using a pure master oscillator (modulator) because

where \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{Kerr}}}}}}}}}\) is the phase noise of the comb-based oscillator, and \({{{{{{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}}}}}_{{{{{{{{\rm{Mod}}}}}}}}}\) is that of the oscillator driving the modulator. At offset frequencies much smaller than the loop bandwidth, the pump phase noise divided by n2 dictates the stability, while at larger offset frequencies the noise of the free-running Kerr frequency comb dominates. Therefore, the resultant phase noise can in some spectral bands be smaller than the fundamental noise of the Kerr comb. A detailed analysis of this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this work.

Conclusion

We introduced a photonic dissipative DTC platform capable of accommodating various DTC states which can be created in a controlled manner and readily identified through subharmonic signatures in the frequency domain. These DTCs are obtained by pumping a Kerr optical resonator with a CW laser which is modulated at integer multiples of the cavity FSR. We described the physics using a mean-filed model (a modified Lugiato–Lefever equation) which vividly manifests the discrete symmetry of this periodically forced system. Exploiting the method of moments, we studied the temporal rigidity of the realizable states, in excellent agreement with numerical results. Finally, we described how the phase noise of the signature RF subharmonic signal accompanying DTC formation can be reduced at small offset frequencies. Besides introducing a robust low–phase-noise microwave and RF signal generation technique, this versatile platform empowers controlled switching between various DTC states by tweaking experimentally available knobs, hence facilitating future studies of DTC phase transitions55,56,57,58.

Methods

Derivation of the model

The governing mathematical model when the modulation frequency to FSR ratio M satisfies M ≥ 1 can be found by first writing the generic evolution equation for the optical signal intensity and phase in each relevant cavity mode, i.e.,

in which Aj(t) is the complex harmonic signal oscillating in the resonator mode with resonance frequency ωj and labeled with the integer j, κj = Δωj denotes the overall decay rate (combining dissipation originating from external coupling, material loss, etc.), Δωj = ωj/Qj being the modal linewidth inversely proportional to the loaded quality factor Qj, κc,j represents the coupling coefficient, and Fj signifies the excitation signal for this mode with frequency ωp,j. The triple-summation on the right-hand side roots in the cubic nonlinearity of the resonator medium and the FWM gain g is proportional to n2, the second-order nonlinear index of refraction, and \({V}_{{j}_{0}}^{-1}\), the inverse of the effective nonlinear mode volume for the pumped mode34. Aj(t) is normalized such that ∣Aj(t)∣2 amounts to the number of photons in the corresponding mode at time t30. When resonator mode j0 is pumped by a CW laser of angular frequency Ω and complex intensity F, pump phase modulation at depth δM creates sidebands for the pump separated by the modulation frequency ωM. For ωM = MD1, this means every Mth neighboring mode of \({\omega }_{{j}_{0}}\) will have an explicit pump signal such that \({F}_{j}={F}_{0}\,{{{{{{{{\rm{J}}}}}}}}}_{j-{j}_{0}}({\delta }_{{{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}}})\) and ωp,j = Ω + kωM, where j = ± kM, k being an integer and Jl indicating the Bessel function of the first kind and of integer order l. The resulting set of couple nonlinear equations in principle model the system and can be integrated upon suitable normalization29. Equation (1) in the main text is arrived at through the discrete Fourier transform of Eq. (4); see, for instance, refs. 23,35 for similar calculations. In deriving this spatiotemporal description, we have ignored the frequency dependence of the Q-factor and coupling coefficients (κj = κ and κc,j = κc for all considered j around j0), an experimentally justified step for a wide range of experiments20, and have utilized the fact that each modal resonance ωj can be linked to the pumped mode \({\omega }_{{j}_{0}}\) using the series expansion \({\omega }_{j}={\omega }_{{j}_{0}}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{m = 1}^{N}{D}_{m}{(j-{j}_{0})}^{m}/m!\), where m and N ≥ 2 are integers. In this expression, D1 denotes the cavity FSR, and Dm for m ≥ 2 are dispersion coefficients17,20.

Pulse momentum equation of motion

In analogy to the quantum mechanical notion of momentum (the wave mechanics perspective), the momentum of the waveform \(\psi (\bar{t},\theta )\) can be defined as

where “c.c.” stands for the complex conjugate of the preceding terms59. Using this definition and Eq. (2) in the main text, an equation of motion in the form

can be derived31. In this expression, the first term on the right-hand side signifies damping rooted in dissipation, and the second term characterizes a time-dependent force given by

where \(F(\bar{t},\theta )\) denotes the overall excitation of the modified LLE, generally depending on both the slow and fast time variables23,31. In the current problem, F is the drive term in Eq. (2), i.e., \(F={f}_{0}\exp \left[{{{{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}}}{\delta }_{{{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}}}\sin (M\theta )\right]\).

To find the force on a soliton, we consider the approximate dissipative soliton waveform \(\psi (\theta )={\tilde{C}}_{1}+{\tilde{C}}_{2}\)sech[B(θ−Θ)], where complex numbers \({\tilde{C}}_{1,2}\) represent the CW background and soliton amplitude, Θ indicates the pulse center, and B−1 is a measure of pulse duration29,50. The force is found as

Here, \(S=\int\nolimits_{-\pi }^{\pi }{{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}}\theta\) sech[B(θ−Θ)] ≈ π/B is the area under the pulse envelope while C2 and ϕ2 are the magnitude and phase of \({\tilde{C}}_{2}\), i.e., \({\tilde{C}}_{2}={C}_{2}\exp ({{{{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}}}{\phi }_{2})\). Subsequently, the potential \({{{{{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}}}}\) trapping the soliton can be calculated noting that \({{{{{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}}}}({{\Theta }})=-{{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}}{{{{{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}}}}/{{{{{{{\rm{d}}}}}}}}{{\Theta }}\), i.e.,

It can readily be verified that for δM of order unity, the force will vanish at fixed points \({{{\Theta }}}_{k}^{* }=(2k+1)\pi /(2M)\), where k is an integer. The potential, on the other hand, will assume the simplified form

with \(a=2S{C}_{2}\cos {\phi }_{2}/M\) and \(b=2S{C}_{2}\sin {\phi }_{2}/(M{\delta }_{{{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}}})\). It has been shown, through the Lagrangian variational approach, that \(\cos {\phi }_{2}=\sqrt{8\alpha }/\pi {f}_{0}\)29. Hence, the potential resembles in essence the phase modulation profile with a negative sign, \(-\sin (M{{\Theta }})\), plus a constant offset, which does not affect stability. Equation (10) is the expression used in the main text. It is noteworthy that the fixed points can also be found using another approach yielding the drift velocity of the solitons under pump modulation60. We adopted the more generic method of moments because it furnishes both the force and the potential felt by pulses, thereby revealing simultaneously the fixed points and the nature of their stability, and offering the intuitive picture of solitons behaving like particles.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sacha, K. Time Crystals (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Wilczek, F. Quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 160401 (2012).

Landau, L. & Lifshitz, E. Course of Theoretical Physics, Vol. 2: The Classical Theory of Fields (Butterworth Heinemann, 1987).

Bruno, P. Impossibility of spontaneously rotating time crystals: a no-go theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 070402 (2013).

Watanabe, H. & Oshikawa, M. Absence of quantum time crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 251603 (2015).

Kozin, V. K. & Kyriienko, O. Quantum time crystals from Hamiltonians with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 210602 (2019).

Else, D. V., Monroe, C., Nayak, C. & Yao, N. Y. Discrete time crystals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 467 (2020).

Gong, Z., Hamazaki, R. & Ueda, M. Discrete time-crystalline order in cavity and circuit QED systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 040404 (2018).

Buča, B., Tindall, J. & Jaksch, D. Complex coherent quantum many-body dynamics through dissipation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1730 (2019).

O’Sullivan, J. et al. Signatures of discrete time crystalline order in dissipative spin ensembles. N. J. Phys. 22, 085001 (2020).

Verstraete, F., Wolf, M. M. & Ignacio Cirac, J. Quantum computation and quantum-state engineering driven by dissipation. Nat. Phys. 5, 633 (2009).

Taheri, H., Matsko, A. B., Maleki, L. & Sacha, K. All-optical dissipative discrete time crystals. Nat. Commun. 13, 848 (2022).

Keßler, H. et al. Observation of a dissipative time crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 043602 (2021).

Kim, K. et al. Spontaneous symmetry breaking of population in a nonadiabatically driven atomic trap: an Ising-Class Phase Transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 150601 (2006).

Yao, N. Y., Nayak, C., Balents, L. & Zaletel, M. P. Classical discrete time crystals. Nat. Phys. 16, 438 (2020).

Kaup, D. J., Newell, A. C. & Longuet-Higgins, M. S. Solitons as particles, oscillators, and in slowly changing media: a singular perturbation theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 361, 413 (1978).

Kovach, A. et al. Emerging material systems for integrated optical Kerr frequency combs. Adv. Opt. Photon. 12, 135 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Monolithic lithium niobate photonic circuits for Kerr frequency comb generation and modulation. Nat. Commun. 10, 978 (2019).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Chip-based self-referencing using integrated lithium niobate waveguides. Optica 7, 702 (2020).

Kippenberg, T. J., Gaeta, A. L., Lipson, M. & Gorodetsky, M. L. Dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Science 361, eaan8083 (2018).

Papp, S., Del’Haye, P. & Diddams, S. Parametric seeding of a microresonator optical frequency comb. Opt. Express 21, 17615 (2013).

Weng, W. et al. Spectral purification of microwave signals with disciplined dissipative Kerr solitons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 013902 (2019).

Taheri, H., Eftekhar, A., Wiesenfeld, K. & Adibi, A. Soliton formation in whispering-gallery-mode resonators via input phase modulation. IEEE Photonics J. 7, 1 (2015).

Jang, J. K., Erkintalo, M., Coen, S. & Murdoch, S. G. Temporal tweezing of light through the trapping and manipulation of temporal cavity solitons. Nat. Commun. 6, 1 (2015).

Lobanov, V. et al. Harmonization of chaos into a soliton in Kerr frequency combs. Opt. Express 24, 27382 (2016).

Cole, D. C. et al. Kerr-microresonator solitons from a chirped background. Optica 5, 1304 (2018).

Obrzud, E., Lecomte, S. & Herr, T. Temporal solitons in microresonators driven by optical pulses. Nat. Photonics 11, 600 (2017).

Brasch, V., Obrzud, E., Obrzud, E., Lecomte, S. & Herr, T. Nonlinear filtering of an optical pulse train using dissipative Kerr solitons. Optica 6, 1386 (2019).

Herr, T. et al. Temporal solitons in optical microresonators. Nat. Photon. 8, 145 (2014).

Chembo, Y. & Yu, N. Modal expansion approach to optical-frequency-comb generation with monolithic whispering-gallery-mode resonators. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033801 (2010).

Taheri, H., Matsko, A. & Maleki, L. Optical lattice trap for Kerr solitons. Eur. Phys. J. D 71, 153 (2017).

Taheri, H. & Matsko, A. Crystallizing Kerr cavity pulse peaks in a timing lattice. In Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science APS/DLS, The Optical Society (Optica Publishing Group, 2019), paper JTu3A.90 (Optical Society of America, 2019).

Taheri, H. & Matsko, A. B. Dually-pumped Kerr microcombs for spectrally pure radio frequency signal generation and time-keeping. In Laser Resonators, Microresonators, and Beam Control XXI, Vol. 10904 (eds Kudryashov, A. V., Paxton, A. H. & Ilchenko, V. S.) 109040P (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2019).

Matsko, A., Savchenkov, A., Strekalov, D., Ilchenko, V. & Maleki, L. Optical hyperparametric oscillations in a whispering-gallery-mode resonator: threshold and phase diffusion. Phys. Rev. A 71, 033804 (2005).

Chembo, Y. & Menyuk, C. Spatiotemporal Lugiato–Lefever formalism for Kerr-comb generation in whispering-gallery-mode resonators. Phys. Rev. A 87, 053852 (2013).

Lugiato, L. A. & Lefever, R. Spatial dissipative structures in passive optical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.2209 (1987).

Coen, S., Randle, H., Sylvestre, T. & Erkintalo, M. Modeling of octave-spanning Kerr frequency combs using a generalized mean-field Lugiato–Lefever model. Opt. Lett. 38, 37 (2013).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Dual-pumped degenerate Kerr oscillator in a silicon nitride microresonator. Opt. Lett. 40, 5267 (2015).

Matsko, A., Savchenkov, A., Ilchenko, V., Seidel, D. & Maleki, L. Hard and soft excitation regimes of Kerr frequency combs. Phys. Rev. A 85, 023830 (2012).

Bao, C. et al. High-order dispersion in Kerr comb oscillators. JOSA B 34, 715 (2017).

Savchenkov, A. et al. Kerr frequency comb generation in overmoded resonators. Opt. Express 20, 27290 (2012).

Herr, T. et al. Mode spectrum and temporal soliton formation in optical microresonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 123901 (2014).

Suh, M.-G. & Vahala, K. Gigahertz-repetition-rate soliton microcombs. Optica 5, 65 (2018).

Boes, A., Corcoran, B., Chang, L., Bowers, J. & Mitchell, A. Status and potential of lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI) for photonic integrated circuits. Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1700256 (2018).

Brasch, V. et al. Photonic chip-based optical frequency comb using soliton Cherenkov radiation. Science 351, 357 (2016).

Guo, H. et al. Universal dynamics and deterministic switching of dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Nat. Phys. 13, 94 (2017).

Fortier, T. M. et al. Generation of ultrastable microwaves via optical frequency division. Nat. Photonics 5, 425 (2011).

Li, J., Yi, X., Lee, H., Diddams, S. & Vahala, K. Electro-optical frequency division and stable microwave synthesis. Science 345, 309 (2014).

Rubiola, E. Phase Noise and Frequency Stability in Oscillators (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Matsko, A. B. & Maleki, L. On timing jitter of mode locked Kerr frequency combs. Opt. Express 21, 28862 (2013).

Taheri, H. In search of time crystalline behavior in Kerr optical frequency combs. In Laser Resonators, Microresonators, and Beam Control XXIII, Vol. 11672 (eds Ilchenko, V. S., Armani, A. M. & Sheldakova, J. V.) 40–44 (International Society for Optics and Photonics (SPIE), 2021).

Liang, W. et al. High spectral purity Kerr frequency comb radio frequency photonic oscillator. Nat. Commun. 6, 1 (2015).

Hajimiri, A. Noise in phase-locked loops. In 2001 Southwest Symposium on Mixed-Signal Design (Cat. No. 01EX475) 1–6 (2001).

Kalia, S. et al. A simple, unified phase noise model for injection-locked oscillators. In 2011 IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium 1–4 (2011).

Surace, F. M. et al. Floquet time crystals in clock models. Phys. Rev. B 99, 104303 (2019).

Yang, X. & Cai, Z. Dynamical transitions and critical behavior between discrete time crystal phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 020602 (2021).

Sakurai, A., Bastidas, V. M., Munro, W. J. & Nemoto, K. Chimera time-crystalline order in quantum spin networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 120606 (2021).

Kuros, A., Mukherjee, R., Mintert, F. & Sacha, K. Controlled preparation of phases in two-dimensional time crystals. Phys. Rev. Research 3, 043203 (2021).

Barashenkov, I. & Zemlyanaya, E. Traveling solitons in the damped-driven nonlinear Schrödinger equation. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 64, 800 (2004).

Firth, W. J. & Scroggie, A. J. Optical bullet holes: robust controllable localized states of a nonlinear cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1623 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The research performed by A.B.M. was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NM0018D0004). H.T. was supported in part by an HBCU/MSI grant from JPL. T.H. acknowledges funding by the Helmholtz Young Investigators Group (VH-NG-1404) and the European Union’s H2020 ERC Starting Grants 853564. K.S. acknowledges the support of the National Science Centre, Poland (Project No. 2018/31/B/ST2/00349).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. and T.H. conceived the idea in collaboration with the other co-authors. H.T. devised the theoretical model, performed numerical simulations, and analyzed the results. A.B.M. developed the phase noise model together with H.T. T.H. contributed to the discussion of experimental aspects and interpretation of the results. K.S. contributed to conceptualization and the analysis of the results. H.T. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Shun Fujii and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taheri, H., Matsko, A.B., Herr, T. et al. Dissipative discrete time crystals in a pump-modulated Kerr microcavity. Commun Phys 5, 159 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00926-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-00926-y

This article is cited by

-

Two-colour dissipative solitons and breathers in microresonator second-harmonic generation

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Topological soliton metacrystals

Communications Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.