Abstract

In viscous, organic-rich aerosol particles containing iron, sunlight may induce anoxic conditions that stabilize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and carbon-centered radicals (CCRs). In laboratory experiments, we show mass loss, iron oxidation and radical formation and release from photoactive organic particles containing iron. Our results reveal a range of temperature and relative humidity, including ambient conditions, that control ROS build up and CCR persistence in photochemically active, viscous organic particles. We find that radicals can attain high concentrations, altering aerosol chemistry and exacerbating health hazards of aerosol exposure. Our physicochemical kinetic model confirmed these results, implying that oxygen does not penetrate such particles due to the combined effects of fast reaction and slow diffusion near the particle surface, allowing photochemically-produced radicals to be effectively trapped in an anoxic organic matrix.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aerosol particles suspended in the atmosphere can take up water and initiate the formation of liquid or ice clouds, impact Earth’s radiative balance1,2, and cause oxidative stress when inhaled affecting respiratory health3,4. Atmospheric aerosol components that generate radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in lungs are linked to toxicity, inflammation, lung disease, and thus, loss of human life4,5,6. Species of ROS include the hydroxyl radical, OH, the hydroperoxyl radical, HO2, the superoxide radical anion, \({\mathrm{O}}_2^ -\), and hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, among others. Of particular interest are carbon-centered radicals (CCRs), such as the methyl radical, •CH3, or the triphenylmethyl radical, •C(C6H5)3, with very different lifetimes. They are some of the many types of radicals that are present in aerosol particles produced from combustion sources, like biomass burning or cigarette smoke; photochemical reactions and aqueous aerosol chemistry; ozonolysis of certain biogenic or anthropogenic gaseous compounds; and biogenic aerosol sources, such as pollen proteins4,5,6,7,8. The lifetimes of ROS and CCRs are typically short due to their high reactivity. Yet, some CCRs can have a lifetime on the order of a day, termed environmentally persistent free radicals (EPFR), which are stabilized with the help of aromatic species or by forming organo-metal complexes in particles or on surfaces5,6,7.

In cold and dry air, aqueous aerosol particles that are dominated by organic solutes may attain a high viscosity9,10 and become solid-like, which slows molecular transport and thus radical chemistry11,12,13. Organic matter is abundant in atmospheric particles and frequently mixes with inorganic and trace metal compounds3,4,6,8,14,15. In atmospheric particles, iron can undergo rapid photochemical cycling leading to radical formation and driving chemical change7,8,16,17,18,19,20,21. Photochemical reactions in aerosol particles occur throughout their bulk and produce CCRs, but we hypothesize that subsequent processes, such as ROS production, evaporation, or gas phase O2 uptake and reaction with CCRs can be significantly stunted by molecular diffusion limitations. Iron(III)-citrate (FeIIICit) photochemistry is representative of iron-carboxylate photochemistry22, which is thought to be a dominant source of OH radicals in atmospheric aerosol particles and the dominant sink of carboxylic acids18,23. FeIIICit undergoes ligand to metal charge transfer (LMCT), iron reduction, and decarboxylation in the same way as many other atmospherically important photoactive iron(III) carboxylate compounds18,23,24. Citric acid is also a well-known proxy for atmospheric organic aerosol particles in terms of composition and viscosity25. Photochemically generated radicals that build up and persist may affect lifetimes of other aerosol-bound species such as pathogens or toxins, with health-related impacts.

Here, we show that photochemically produced CCRs are immobilized in highly viscous organic aerosol particles and act as a major sink for O2 inside particles, thereby inducing anoxia. Atmospheric aerosol anoxia is highly unexpected since the time it takes for small molecules, such as water and possibly oxygen, to diffuse and mix throughout non-reactive viscous particles is thought to be on the order of seconds to minutes at ambient conditions11,13,26,27. However, we found that it is the combined effects of reaction and diffusion limitations that ROS and CCRs can persist and accumulate in viscous aerosol particles and completely overwhelm O2 in their interior. This occurs under both cold and warm conditions, but largely depending on the relative humidity, RH, particles are exposed to. Persistent ROS and CCR species can then be released under more humid conditions, e.g., upon inhalation, which will exacerbate the negative health effects of aerosol exposure beyond what is expected when assuming a well-mixed and a highly reactive aerosol matrix during their airborne trajectory.

Results

Looking inside single particles for their chemical morphology

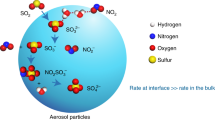

The FeIIICit photochemically reactive system shown in Fig. 1a was employed to produce CCRs in the presence of O2, the gas phase reactant of interest. We used a triad of photochemical experiments to observe photochemical reaction cycles on the nanoscale and microscale in single particles and films including scanning transmission X-ray microscopy coupled with near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (STXM/NEXAFS) spectroscopy, a single particle electrodynamic balance (EDB), and a coated-wall flow tube (CWFT). Our multifarious observations were supported by a recent photochemical reaction and diffusion (PRAD) model28,29. We observed that photochemically produced CCRs induce anoxia in the interior of viscous particles, effectively preserving CCRs under dry conditions. Figure 1 shows viscous FeIIICit particles during photochemical cycling, where an oxidized shell and unoxidized core is depicted by the color gradient (Fig. 1a). This oxidation configuration was directly observed using STXM/NEXAFS to image iron(III) fraction, β, acquired minutes after photoreduction and reoxidation (Fig. 1b). These low β values are indicative of LMCT, i.e., charge transfer from the citrate ligand to Fe3+, forming Fe2+ and a primary radical product, which immediately decays by decarboxylation (i.e., the removal of a carboxyl group via loss of CO2). Then, an organic, carbon-centered radical, the primary CCR, is left behind28. Following the reaction steps in Fig. 1a, ROS is generated when O2 is taken up by the particle and reacts with photochemically generated CCRs, through mostly a first generation of peroxy radicals. Finally, iron(II) can be reoxidized by ROS or O2, then complexed again with citric acid. Low values of β observed within particles also imply an absence of the O2 and ROS needed for oxidation and thus a persistence of CCRs. We observed 2-D column integrated profiles (i.e., in the same dimension as the 2-D microscope image) of β in aerosol particles evolving in the dark at RH = 40, 50, and 60%, Fig. 1c–e respectively, to discover where oxidation occurred inside single particles. At RH = 40%, β remained low and indicated that CCRs remained at high concentrations and unreacted. Gradients in β were observed at all RH, but most discernable for RH ≤ 50% and extended throughout the interior of particles. At RH = 60%, profiles of β were relatively flat from the perimeter to the center of particles (Fig. 1e). This indicates a transition from an inhomogeneous state, characterized by anoxic conditions at RH = 40%, to homogeneous, well-mixed conditions enhancing O2 concentrations in the bulk. Therefore, we conclude that altering RH significantly alters the diffusion coefficients of reactants and products, and so controls whether or not radicals are built up or reacted away quickly.

a Sketch of FeIIICit photochemical cycling in a particle oxidized near its surface (green) and anoxic in its bulk (gray). Purple, blue, and red text indicate specific species discernable using scanning transmission X-ray microscopy coupled to near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy (STXM/NEXAFS), an electrodynamic balance (EDB) and coated wall flow tube (CWFT) methods, respectively. Solid lines are chemical reactions, e.g., ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT) reaction, dashed lines are equilibria conditions, and dash-dotted lines indicate gas evaporation or uptake. Citrate, the iron(II)-citrate complex, and CH2COOH are abbreviated as Cit3-, FeIIHCit, and R, respectively. b A STXM/NEXAFS image of the iron(III) fraction, β, in particles directly showing reoxidation only near the surface of particles. The image was smoothed by increasing the pixel resolution and interpolating. c–e Chemical gradients inside particles as a function of time, t (color coded), and relative humidity, RH, during dark reoxidation at 20 °C after 15 min of UV light exposure. At RH = 40% (c), dark reoxidation occurred slowly while maintaining gradients in β. Reoxidation at RH = 50% (d) and 60% (e) was faster, implying that particles took up more water resulting in greater diffusion coefficients, hence faster molecular transport and oxidation reaction. Gray symbols are the measured initial iron(III) fraction, β0, from multiple images acquired before UV light exposure. Example error bars, Δβ = ±0.07, are shown. Solid colored lines are derived from the photochemical reaction and diffusion (PRAD) model and reproduce our observations. Details on model sensitivity are given in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 3).

X-ray imaging shows that oxidation occurred near particle surfaces, but not in their bulk. Therefore, photochemically generated CCRs present in the bulk must have had long lifetimes due to slow molecular transport and reaction with O2 as their main reaction partner. Additional images that support this finding acquired at the start and end of STXM/NEXAFS experiments are given in Supplementary Fig. 1. We used the PRAD model28 to simulate radical persistence due to photochemical reduction and dark reoxidation experiments performed with STXM/NEXAFS (solid lines in Fig. 1c–e). Modeled profiles of β reproduce our observations only when the modeled O2 concentration drops to zero just nanometers beneath the surface of an aerosol particle as shown in the radial profiles in Supplementary Fig. 2. The accumulation of CCRs in anoxic particle interiors is the necessary condition to explain the spectroscopically observed iron oxidation state, pointing to long radical lifetimes in photoactive, viscous aerosol particles. When particles with high radical concentration are inhaled, they may release CCRs and ROS in the respiratory tract. It is conceivable that the saturated lung environment lets non-organic and iron species undergo chemical cycling to produce even more ROS and CCRs, exacerbating lung tissue damage.

Photochemical evolution of particle mass loss and radical release

We irradiated single particles, which were levitated in an EDB, with visible light for more than 5 h (Fig. 2a) and observed their continual size decrease. Under humid conditions (RH = 50%), a 1 µm decrease in particle radius, r, was observed (symbols), i.e., about 12% of its initial value, r0 = 8 µm. This is equivalent to a ∼33% mass loss. In contrast, at RH = 16%, irradiation caused only a 30 nm decrease in r, i.e., about ∼0.4% in r. This small mass loss was due to the fact that ROS and CCR, though continuously produced, did not produce and release significant amount of CO2 or volatile compounds to the gas phase. In general, EDB observations are master constraints for modeling radical chemistry occurring in the condensed phase of citric acid initiated by photolysis of iron carboxylate complexes28. All modeled radii decrease (solid lines) for all RH shown in Fig. 2a, which is in agreement with our data. The decrease in r accelerated, as seen in Fig. 2a, which is likely the result of CO2 release and volatile product formation (indicated as C2–5 in Fig. 1a) and their increasing evaporation at later times. We note that accelerated decrease in r may be counter to a competitive CCR recombination reaction, in which CCRs would destroy themselves, leading to less volatile, higher molecular weight products such as oligomers30. We have found evidence shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 that CCR recombination may occur on long time scales, which is likely not significant enough to affect the observed fast photochemical cycling resulting in the loss of mass. Although radical reactions are typically fast in dilute solution31, they can be limited due to diffusion-controlled reaction32. In conjunction, CCRs may also become stabilized with iron6,7, in line with our hypothesis that they persist in anoxic viscous organic particles (see Supplementary Fig. 4). Unimolecular radical reactions are known to eliminate CO2 and HO2, as observed here16,18,22,23,24,31,33,34,35. In other cases, elimination reactions may result in producing new radicals, and not their overall destruction (e.g., H2O elimination followed by glycol radical production)36. We speculate that an elimination reaction for CCRs would likely contribute to the production of CO2, VOCs, and small radical compounds, and therefore propagate radical persistence and continued radical chemistry. The PRAD model reproduces our results when CCR self-reaction is turned off, indicating that ROS and CCR turnover is important near the surface of particles where oxidation takes place, and that the lifetime of CCRs must be long in the cores of the particles.

a Electrodynamic balance experiments determined that particle radius, r(t), decreased over time, t, during light exposure (r0 = r(0)) due to the release of CO2 and other volatile species. Error bars indicate the range of possible refractive index values from any changes in composition during irradiation. The solid lines were derived from the photochemical reaction and diffusion (PRAD) model, and the shading is the model sensitivity to ±2% in relative humidity, RH. b Measured steady-state production of HO2, \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\), from coated wall flow tube experiments is shown as a function of the mole ratio between Fe(III)-citrate and citric acid, Mr (blue), and film thickness (red) indicated by symbols. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of multiple measurements or the propagated random error from solution preparation, whichever is larger. Dotted and dashed lines were determined from the PRAD model with kSR = 8.3 × 105 M−1 s−1 in dilute aqueous solution, or using the parameterization \(\begin{array}{l}\log k_{{\mathrm{SR}}} = - 2.854 \times 10^{ - 5}{\mathrm{RH}}^3 + 0.0024{\mathrm{RH}}^2 + 0.1087{\mathrm{RH}} - 0.05018,\end{array}\) respectively28. Here, M is molarity in units of mole L−1. Solid lines were from the PRAD model using fitted HO2 loss rates shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The shading is the model sensitivity to a factor of 5 uncertainty in the HO2 loss rate.

Finally, the CWFT experiments shown in Fig. 2b show a steady-state production and release of HO2 radicals, \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\), demonstrating continual ROS production from photochemical cycling of FeIIICit. This radical source was due entirely to O2 uptake and reaction. Increasing the FeIIICit to citric acid mole ratio, Mr, led to an increase in \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\), which was expected since a greater number of photochemically active reactants should increase ROS and CCR. At our lowest investigated Mr = 0.01, the PRAD model still predicts anoxic conditions and CCR persistence as seen in Supplementary Fig. 5. We also show a typical time-resolved radial profile of HO2 concentration in Supplementary Fig. 5c, where the maximum occurs when CCR and O2 concentration within particles drops significantly. We also observed that \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) increased by a factor of 1.5 for film thicknesses 0.18–0.89 µm; however, this is far less than our error estimate from the HO2 loss rate. If there were a large gradient in O2 concentration over this range, we would expect \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) would significantly depend on film thickness. As this was not the case, O2 penetration must have been much smaller than 0.18 µm, in agreement with STXM and EDB observations and modeling results. Recent ambient observations of soluble iron and ligand concentration in aerosol particles20,21 discussed later have shown that the mole ratio between iron organic complexes and organic compounds can be on the order of Mr = 10−1, which is consistent with the range in our CWFT and EDB experiments.

The observation of steady-state \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) was the key observable of ensuing peroxy radical chemistry in the condensed phase. The PRAD model over predicted \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) when using a HO2 self-reaction rate coefficient, kSR = 8.3 × 105 M−1 s−1, from dilute aqueous solution or using a previous parameterization by Dou et al.28 as a function of RH. Here, M is molarity in units of mole L−1. It appears that the condensed phase HO2 sink was greater than only considering its self-reaction and iron reoxidation by roughly 1 order of magnitude, indicating a central role of the organic peroxy radicals in the photochemical cycling, which are presently not known and not included in detail in the PRAD model. The PRAD model captured observed \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) only when fitting the HO2 loss rate as described in the Supplementary Discussion (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Measurements of \(P_{{\mathrm{HO}}_2}\) in dependence of film thickness and O2 partial pressure (Supplementary Fig. 6), measurements as a function of RH from Dou et al.28, and PRAD model results all allowed to confine primary peroxy radical formation to the outermost surface where O2 was still present. This reveals that H2O2 and likely second-generation peroxy radicals penetrated over depths larger than expected from its self-reaction. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows that H2O2, in particular, is a large contributor to the overall ROS concentration in the PRAD model. This is because the 1st order chemical loss rate of H2O2 is slow (on the order of 10−4 s−1) and its solubility is high. Therefore, it has a high concentration in the condensed phase and enough time to diffuse through the particle. Calculated depth profiles of HO2 concentrations in films are shown in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 7 along with organic CCR, ROS, and O2 concentrations. Again, the PRAD model predicts complete O2 depletion at a short depth beneath the surface. Despite this limitation, any peroxy radical or hydroperoxides would contribute to the total ROS concentration, giving confidence to our quantification of ROS production for reoxidation and photochemical cycling. As mentioned above, HO2 peaked where O2 and CCRs were depleted, highlighting the importance of the reaction between them. In addition to EDB and STXM/NEXAFS experiments with high CCR concentrations, CWFT experiments further indicate that ROS existed at high concentrations, apparently replenished by the accelerating photochemical cycling.

Discussion

The importance of oxygen limitation in photoactive particles is underscored by comparing environmentally persistent free radical concentrations [EPFR] in ambient air with our predictions. A previous study observed [EPFR] = 1010–1012 (molecules) μg−1 of aerosol mass, attributable to the presence of quinones and transition metals5. In highly viscous FeIIICit and citric acid particles (RH = 20%), the ROS concentration, [ROS] = 2.7 × 1010 μg−1 and the CCR concentration was [CCR] = 1.5 × 1012 μg−1 at a quasi-steady state (Supplementary Fig. 7c). This emphasizes the importance of a persistent radical source from photochemistry, which is comparable to that of quinone and metal aerosol components. Compared to the range of values reported by ambient measurements, radical concentrations are not highly dependent on particle diameter between 0.03–1.0 µm (Supplementary Fig. 8). One caveat to predicting radical concentrations here is that we do not consider additional factors such as different morphologies, chemical inhomogeneity, or other competing atmospheric processes15, which may systematically enhance or hinder ROS and CCR buildup. In highly viscous particles, radicals are immediately produced and maintained over the course of hours as seen in Supplementary Fig. 7c. In lower viscosity particles, radicals are immediately produced, but subsequently drop by orders of magnitude. This implies that aerosol microphysics, and thus molecular diffusion, can change the progression of reactions tending toward drastically different outcomes in radical concentration. Previous measurements used electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy on ambient particles collected on filters, which were then submerged in dilute aqueous solutions mimicking endogenous radical production in lungs and containing a radical trapping compound to quantify them5. Prior filter storage will probably lead to the loss of radicals exogenously produced due to aerosol photochemistry and thus would not be included in EPR analysis. Considering persistent radicals in aerosol particles due to photochemical processing may result in larger radical concentration compared to what is measured with filter methods or offline analysis. Therefore, there is a high risk to underestimate radical numbers in aerosol particle populations37,38 affecting a variety of consequences including the adverse health effects these particles cause3,4,6,7,8,14.

The range of atmospheric conditions under which ROS and CCRs can persist in aerosol populations is shown in Fig. 3 as a function of temperature, T, RH, Mr, and the photochemical reaction rate, j. Conditions at which RH = 40–50% over T = 0–25 °C marks a transition between CCR buildup and depletion in aerosol particles entirely due to changing diffusion coefficients. Trends in [ROS] and [CCR] were similar as seen in Supplementary Fig. 9. At constant T and RH, [ROS] increased with Mr and reached a maximum of about 7 mM between Mr = 0.04–0.3. Inhaled particles with this level of exogenously produced ROS may contribute significantly to the total production in lungs (exogenous and endogenous), which is discussed in more detail in the Supplementary Information. When Mr increased further, [ROS] sharply decreased as seen in Fig. 3b. This was because O2 loss from CCR reaction became so extreme that O2 penetration, and thus ROS production became limited to <0.3 nm beneath the surface, i.e., the molecular scale. Additionally, an excess of Fe2+ resulted in a short ROS lifetime. In the PRAD model, diffusion coefficients for Mr > 0.05 decrease, which is evident from measured viscosities at Mr = 1.0 and 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 11), contributing to this sub-nanometer penetration depth. Overall, we argue that ROS and CCR build-up in aerosol particles at the Earth’s surface are controlled, in part, by meteorological conditions and aerosol composition.

a CCR concentration, [CCR], as a function of temperature, T, and relative humidity, RH, in particles is shown. High [CCR] occurred primarily at drier conditions and lower T to a lesser degree. b ROS concentration, [ROS], as a function of the mole ratio between iron(III)-citrate (FeIIICit) and citric acid, Mr, and the photochemical reaction rate, j. The maximum ordinate value, j = 5.23 × 10-2 s-1, corresponds to the photochemical dissociation rate for FeIIICit with a light intensity at the Earth’s surface at 0° zenith. Mr and j values in a are indicated by the circle in b. T and RH values in b are indicated by the cross in a. [CCR] and [ROS] were averaged over the last 30 min for a particle having a radius of 0.5 µm in a 1 h simulation using the photochemical reaction and diffusion (PRAD) model. Dashed colored rectangles indicate the range of values for various field studies held in the southern Great Plains, USA17 (purple), Aksu, China19 (blue), urban centers in Canada20 (white), the Po Valley of Italy21 (green), and Okinawa Island39 (red) detailed in the Supplementary Information.

The rectangles in Fig. 3 allow comparing our estimates of ROS and CCR build-up with those previous field studies17,19,20,21,39, which detail aerosol composition, and specifically iron concentration, solubility, or speciation. We estimated Mr from previous studies using measured aerosol composition and 3 conservative assumptions, (i) that a fraction of iron in particles is soluble, (ii) that a fraction of soluble iron is in complex with carboxylate compounds, and (iii) that only a fraction of total particles (by number) contain iron. More details on estimates of Mr are in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Table 2. In more continental and drier climates, as was the case for field studies in central China19 and the Great Plains of the USA17 (shown as the blue and purple boxes), T and RH were sufficiently low on average to promote radical buildup. In other field studies in Okinawa Island39, multiple urban sites in Canada20 and in the Po Valley of Italy21, climates are more humid on average. This implies that high [CCR] and [ROS] should occur across the Earth where aerosol particles are more viscous with long mean equilibrium mixing times, as previously reported40. Even under warm or humid average meteorological conditions, cold or dry weather spells can still lead to episodes of high radical concentrations. In the Po Valley of Italy21, metal concentrations were similar to other European urban areas with abundant iron carboxylate complexes (green box in Fig. 3). Therefore, we argue that iron carboxylate complexes are an ubiquitous aerosol component, in line with previous studies quantifying organic matter with carboxyl functions and iron in ambient particles10,18,39. These can lead to aerosol anoxia and a consistent source of aerosol-borne CCRs and ROS.

A large radical source due to iron carboxylate photochemistry has important implications for other atmospheric photoactive aerosol components and the lifetime of air mass tracer compounds, pathogens or toxic compounds posing a health risk. Common atmospheric brown carbon compounds such as imidazoles41,42, quinone containing compounds6,43, or humic-like substances (HULIS)44 are photoactive and may limit O2 penetration if they produce sufficient radical numbers with low diffusion coefficients. Secondary organic aerosol particles are highly viscous11,12,25,40 and photochemical aging may generate radical compounds within them that are preserved. Therefore, we strongly suggest that radical production and persistence along with anoxia may be possible with all photoactive aerosol compounds given sufficient concentration and aerosol viscosity to cause anoxia due to both reaction and diffusion limitations. The transition region for CCRs and ROS at intermediate RH as revealed in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 9 delineates conditions where radical concentration within particles is still high, but their mobility is substantial enough to exert a significant role in condensed phase aging, e.g., impacting the chemical turnover of harmful organic toxins or tracer compounds for aerosol source apportionment. This transition also coincides with the RH range where the lifetime of viruses suspended in exhaled human respiratory particles is shortest45. Exhaled particles of lung-lining fluid are composed of, in part, proteins, saccharides, and iron, which may be highly viscous, susceptible to photochemical radical buildup and impact pathogen viability. Quantifying the link between environmental parameters and aerosol photochemistry as done for the iron carboxylate complexes here will greatly improve our understanding of condensed phase chemistry, radical process, and controls on human exposure to particulate matter that are detrimental to health.

Methods

Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy coupled to near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (STXM/NEXAFS) spectroscopy experiments

We recently developed a photochemical reactor at the PolLux beamline46 of the Swiss Light Source to expose particles containing citric acid and FeIIICit to UV light under atmospherically relevant RH and T47,48. The main advantage of STXM/NEXAFS spectroscopy is the coupling of high-spatial resolution and chemical selectivity for organic carbon functionality and iron oxidation state, and effectively mapping chemical reactions in particles in real-time and in situ46,49,50. All particles in the three STXM/NEXAFS experiments were exposed to O2 at a partial pressure of 112, 107, and 104 mbar, at RH = 40, 50, and 60%, respectively. Helium was the carrier gas for O2 and H2O with a total flow of 20 mL min−1 at standard temperature and pressure. The total pressure in the environmental chamber was 150 mbar. The iron oxidation state within single particles containing FeIIICit and citric acid was measured using STXM/NEXAFS. A solution having Mr = 1.0 was prepared and nebulized to generate droplets that were subsequently dried at RH < 30% and impacted onto X-ray transparent membranes51. These particles on membranes were then placed in an environmental chamber set inside the X-ray microscope47. At all steps, we avoided ambient light and humidity exposure and kept particles in a dry, dark vacuum container prior to use. The time between particle generation and use in STXM/NEXAFS experiments was <2 h. We used STXM/NEXAFS to measure transmitted X-ray photons through a square spot, or pixel, 35 × 35 nm2 in size46. A 5 × 5 µm2 image contained 20,400 pixels, each making up either the transmitted photon count mapped across a particle, I, or quantifying the background signal, I0. From this, the optical density, OD = -ln(I/I0), at each pixel was determined. Acquiring multiple images as a function of X-ray energy yielded a NEXAFS spectrum, which was used to obtain absorption peaks of FeIIICit over the L-edge of iron (700–735 eV) and the K-edge of carbon (280–320 eV). Additionally, we imaged OD at two X-ray energies, 707.8 and 709.5 eV, which correspond to the peak resonant X-ray absorption by iron(II) and iron(III) species, respectively. Energy calibration and determination of non-resonant absorption followed previous work, including a procedure to evaluate X-ray beam damage and avoid it entirely51. Image analysis was based on publicly available software tools50. Using the parameterization in Moffet et al.39 and following an imaging procedure in Alpert et al.51, we mapped the iron(III) fraction out of the total iron, β, with a time resolution on the order of minutes. Maps were used to derive 2-D β-profiles (Fig. 1c, d) following Alpert et al.51, by averaging β over the perimeter pixels (1 pixel from the perimeter) and those concentric pixels toward the center (>2 pixels from the perimeter). In line with previous studies51,52,53,54,55,56, our particles were determined to be half-spheres, evident from their morphology and OD profiles of particles compared with known spherical polystyrene particles. We note that a single profile, i.e., one color in Fig. 1c, d correspond to a single image of multiple particles (5–20) with >10,000 pixels, where each pixel quantifies iron oxidation state over an area of 1.2 × 10−3 µm2. Uncertainty in β was determined as, Δβ = ±0.07 or propagated from the photon counting error, whichever was larger51. Prior to illumination, initial β-profiles were determined. A UV-LED fiber optic coupling to the STXM chamber was custom-built utilizing UV compatible components and optics, which resulted in a uniformly illuminated sample area with a measured power density of 3.6 ± 0.6 mW mm−2 in the narrow wavelength range of 364–370 nm, equivalent to j = 2.2 ± 0.04 × 10−3 s−1 when accounting for the absorption cross section. Illumination for all samples then lasted for 15 min with a UV LED. Immediately after the light was switched off, we continually mapped β over multiple particles while re-oxidation took place under a constant RH and O2 gas phase concentration, unless otherwise specified. A different procedure is outlined in the Supplementary Information for the data specific to Supplementary Fig. 4 in order to elucidate the radical lifetime. Briefly, this involved photochemical reduction in helium, without the presence of O2, and waiting 35 min or 9 h before O2 was introduced.

Electrodynamic balance (EDB) experiments

Experiments using an EDB28,57 were performed to measure the mass loss of aqueous particles irradiated by a frequency-doubled diode laser with a wavelength of 473 nm in the visible. In the experiments, the power density was 40 mW mm−2 at all RH except for RH = 47%, where it was 20 mW mm−2 (j = 4.3 × 10−3 and 2.2 × 10−3 s−1, respectively). Aqueous solutions having Mr = 0.05 were prepared and used to generate an aqueous particle injected into the RH and T controlled EDB chamber. The injected particle was given ample time to equilibrate with water vapor in an O2 atmosphere at a pressure of 800 mbar. The aqueous solution and particle were kept in the dark at all steps prior to irradiation. Before and after the laser was switched on, the particle radius change was monitored over time and the mass loss determined. For each investigated RH, a new particle from a freshly prepared solution was used. The EDB applies a high AC voltage across two electrode rings and a DC voltage across hyperbolic end-caps to generate an electric field to levitate particles. The electric field was adjusted automatically to compensate the gravitational force on the particle as its size changed. The refractive index and size of spherical particles were determined from measurements of backscattered light from a broad-band LED centered around 640 nm. The radius loss in Fig. 2a was determined from the ratio between the particle radius over time, r(t), and the radius prior to illumination, r0 = r (t = 0). Due to the high accuracy of determining mass and radius loss, the main source of error was due to the unknown change in refractive index from any changes in composition during irradiation.

Coated wall flow tube (CWFT) experiments

The release of HO2 into the gas phase was measured in CWFT experiments through the efficient scavenging reaction with excess NO42,58,59. Films were generated by dispensing a known volume of aqueous FeIIICit and citric acid solutions with Mr from 0.01 to 0.11 in Duran glass tubes 1.2 cm in diameter and 50 cm long. The error on Mr, ΔM, was ±7% on its measured value. Solutions and prepared films were always kept in the dark prior to use. Calculated film thickness was between 0.2–1.8 µm with an approximate ±20% uncertainty and accounted for water uptake at a given RH. When thickness was varied, Mr = 0.0784 and RH = 38.5%. When Mr was varied, thickness was 1.1 µm and RH = 37%. Films were allowed to equilibrate to RH prior to the start of an experiment. Uncertainty in RH was ΔRH = ±2%. A constant flow rate of N2 and O2 was used, typically at a 20% O2 content. We also performed O2-dependent experiments by varying the partial flow rates, but maintaining a constant total flow, either 1.0 or 0.5 L min−1. Prior to illumination, a baseline NO concentration was determined. Illumination using up to 7 fluorescent tubes were then switched on simultaneously causing a drop in NO concentration. This drop was used to calculate the HO2 release from the film following a previous procedure42. The NO conversion was routinely checked to exclude processes involving NO and HO242,58, such as a loss due to O3 formation, a production due to the photolysis of NO2 and the return of HO2 to the film. We note, gas phase loss of HO2 with volatile organic compounds is highly unlikely to affect NO conversion as known reaction rates are far too slow. We cycled all films with intervals of UV light switched off and on for approximately 0.5–2 h per interval. Loss of NO and recovery were reproducible to within about 10%, which emphasizes the robustness of our system and our instrument precision. The light output of our fluorescent tubes had a broadband spectrum >300 nm in wavelength and extended into the visible spectrum. Utilizing the measured wavelength-dependent irradiance42, absorption cross section33, and the quantum yield28, we calculated that j = 9.1 × 10−3 s−1, which is higher than that used in STXM or EDB experiments.

Photochemical reaction and diffusion (PRAD) model

The PRAD model was developed to describe the FeIIICit system constrained with experimental data. It utilizes physical and chemical parameters, such as molecular diffusion coefficients and Henry’s law constants for molecular transport and solubility of the multiple species represented, as well as chemical parameters, such as reaction rates and equilibrium constants. All observables in STXM/NEXAFS, EDB, and CWFT experiments are explicitly modeled and are directly compared. The condensed phase is separated in multiple layers each hosting photochemical reactions, chemical reactions and imposing equilibria conditions first, followed by modeling the flux of molecules between the layers. Details of the PRAD model are given in Dou et al.28, and those pertinent to this study are reviewed below. Diffusion coefficients of all species were scaled with the diffusion coefficient of water, Dw, i.e., the diffusion coefficient of a species x is Dx = DwfDx, where fDx is a species-specific constant. We have observed that solution viscosity increased significantly when Mr > 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 11), therefore we have decreased Dw with increasing Mr. For example, Dw was parameterized to increase by a factor of ~4 from Mr = 0.05 to 1.028. Known equilibrium coefficients for dissociation and complex formation, photochemical reaction rates, and chemical reaction rate coefficients were determined from previous literature28. Unknown equilibrium coefficients and rate coefficients were globally fit to all STXM/NEXAFS, EDB, and CWFT experimental results simultaneously28. Henry’s law constants for O2, ROS, and other volatile compounds were also adjusted to match observations28 and were typically about 1 order of magnitude higher than those reported in dilute aqueous solution. Dou et al.28 reported an observed mass loss with UV light exposure using a quantum yield, Φ = 1.0, for wavelengths, λ < 400 nm28. In order to reproduce our observations in the EDB, we used Φ(473 nm) = 0.002 following our previous work57. A parameterization of Φ as a function of λ was formulated28 and used to predict j for CWFT experiments and for j due to sunlight reaching the Earth’s surface, which was determined with the online TUV calculator, http://cprm.acom.ucar.edu/Models/TUV/Interactive_TUV/, as a function of solar zenith angle.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3817356.

Code availability

The PRAD model code that support the findings of this study can be found in Dou et al.28.

References

Knopf, D. A., Alpert, P. A. & Wang, B. The role of organic aerosol in atmospheric ice nucleation: a review. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2, 168–202 (2018).

Boucher, O. et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367 (2015).

Dockery, D. W. & Pope, C. A. Acute respiratory effects of particulate air pollution. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 15, 107–132 (1994).

Arangio, A. M., Tong, H., Socorro, J., Pöschl, U. & Shiraiwa, M. Quantification of environmentally persistent free radicals and reactive oxygen species in atmospheric aerosol particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 13105–13119 (2016).

Shiraiwa, M., Selzle, K. & Pöschl, U. Hazardous components and health effects of atmospheric aerosol particles: reactive oxygen species, soot, polycyclic aromatic compounds and allergenic proteins. Free Radic. Res. 46, 927–939 (2012).

Gehling, W. & Dellinger, B. Environmentally persistent free radicals and their lifetimes in PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 8172–8178 (2013).

Tong, H. et al. Reactive oxygen species formed in aqueous mixtures of secondary organic aerosols and mineral dust influencing cloud chemistry and public health in the Anthropocene. Faraday Discuss 200, 251–270 (2017).

Ault, A. P. & Axson, J. L. Atmospheric aerosol chemistry: spectroscopic and microscopic advances. Anal. Chem. 89, 430–452 (2017).

Laskin, A., Gilles, M. K., Knopf, D. A., Wang, B. & China, S. Progress in the analysis of complex atmospheric particles. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 9, 117–143 (2016).

Koop, T., Bookhold, J., Shiraiwa, M. & Pöschl, U. Glass transition and phase state of organic compounds: dependency on molecular properties and implications for secondary organic aerosols in the atmosphere. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19238–19255 (2011).

Shiraiwa, M. et al. Global distribution of particle phase state in atmospheric secondary organic aerosols. Nat. Commun. 8, 15002 (2017).

Zobrist, B., Marcolli, C., Pedernera, D. A. & Koop, T. Do atmospheric aerosols form glasses? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 5221–5244 (2008).

Mauderly, J. L. & Chow, J. C. Health effects of organic aerosols. Inhal. Toxicol. 20, 257–288 (2008).

Takahama, S., Gilardoni, S. & Russell, L. M. Single-particle oxidation state and morphology of atmospheric iron aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D22202 (2008).

Grgić, I. in Environmental Chemistry of Aerosols (ed Colbeck, I.) (Blackwell Publishing, 2008).

Hand, J. L., Gill, T. E. & Schichtel, B. A. Spatial and seasonal variability in fine mineral dust and coarse aerosol mass at remote sites across the United States. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 3080–3097 (2017).

Herrmann, H. et al. Tropospheric aqueous-phase chemistry: kinetics, mechanisms, and its coupling to a changing gas phase. Chem. Rev. 115, 4259–4334 (2015).

Takahashi, Y., Higashi, M., Furukawa, T. & Mitsunobu, S. Change of iron species and iron solubility in Asian dust during the long-range transport from western China to Japan. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 11237–11252 (2011).

Tao, Y. & Murphy, J. G. The mechanisms responsible for the interactions among oxalate, pH, and Fe dissolution in PM2.5. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 2259–2265 (2019).

Tapparo, A. et al. Formation of metal-organic ligand complexes affects solubility of metals in airborne particles at an urban site in the Po valley. Chemosphere 241, 125025 (2020).

Cieśla, P., Kocot, P., Mytych, P. & Stasicka, Z. Homogeneous photocatalysis by transition metal complexes in the environment. J. Mol. Catal. A 224, 17–33 (2004).

Weller, C., Tilgner, A., Bräuer, P. & Herrmann, H. Modeling the impact of iron–carboxylate photochemistry on radical budget and carboxylate degradation in cloud droplets and particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 5652–5659 (2014).

Weller, C., Horn, S. & Herrmann, H. Photolysis of Fe(III) carboxylato complexes: Fe(II) quantum yields and reaction mechanisms. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 268, 24–36 (2013).

Reid, J. P. et al. The viscosity of atmospherically relevant organic particles. Nat. Commun. 9, 956 (2018).

Berkemeier, T., Shiraiwa, M., Pöschl, U. & Koop, T. Competition between water uptake and ice nucleation by glassy organic aerosol particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 12513–12531 (2014).

Lienhard, D. M. et al. Viscous organic aerosol particles in the upper troposphere: diffusivity-controlled water uptake and ice nucleation? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 13599–13613 (2015).

Dou, J. et al. Photochemical degradation of iron(III) citrate/citric acid aerosol quantified with the combination of three complementary experimental techniques and a kinetic process model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 315–338 (2021).

Bastelberger, S., Krieger, U. K., Luo, B. & Peter, T. Diffusivity measurements of volatile organics in levitated viscous aerosol particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 8453–8471 (2017).

Renard, P. et al. Radical mechanisms of methyl vinyl ketone oligomerization through aqueous phase OH-oxidation: on the paradoxical role of dissolved molecular oxygen. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 6473–6491 (2013).

Simic, M., Neta, P. & Hayon, E. Pulse radiolysis of aliphatic acids in aqueous solutions. II. Hydroxy and polycarboxylic acids. J. Phys. Chem. 73, 4214–4219 (1969).

Arangio, A. M. et al. Multiphase chemical kinetics of OH radical uptake by molecular organic markers of biomass burning aerosols: humidity and temperature dependence, surface reaction, and bulk diffusion. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4533–4544 (2015).

Pozdnyakov, I. P. et al. Photophysics of Fe(III)–tartrate and Fe(III)–citrate complexes in aqueous solutions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 530, 45–48 (2012).

Ulanski, P., Bothe, E., Hildenbrand, K., Rosiak, J. M. & von Sonntag, C. Hydroxyl-radical-induced reactions of poly (acrylic acid); a pulse radiolysis, EPR and product study. Part II. Oxygenated aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 23–28 (1996).

von Sonntag, C. & Schuchmann, H.-P. The elucidation of peroxyl radical reactions in aqueous solution with the help of radiation-chemical methods. Angew. Chem. 30, 1229–1253 (1991).

Burchill, C. E. & Perron, K. M. Radiation-induced rearrangement of ethylene glycol in aqueous solution. Can. J. Chem. 49, 2382–2389 (1971).

Paulson, S. E. et al. A light-driven burst of hydroxyl radicals dominates oxidation chemistry in newly activated cloud droplets. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav7689 (2019).

Arellanes, C., Paulson, S. E., Fine, P. M. & Sioutas, C. Exceeding of Henry’s law by hydrogen peroxide associated with urban aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 4859–4866 (2006).

Moffet, R. C. et al. Iron speciation and mixing in single aerosol particles from the Asian continental outflow. J. Geophys. Res. 117, D07204 (2012).

Shiraiwa, M. & Seinfeld, J. H. Equilibration timescale of atmospheric secondary organic aerosol partitioning. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L24801 (2012).

Teich, M., van Pinxteren, D., Kecorius, S., Wang, Z. & Herrmann, H. First quantification of imidazoles in ambient aerosol particles: potential photosensitizers, brown carbon constituents, and hazardous components. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1166–1173 (2016).

Corral Arroyo, P. et al. Particle-phase photosensitized radical production and aerosol aging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7680–7688 (2018).

Scharko, N. K., Martin, E. T., Losovyj, Y., Peters, D. G. & Raff, J. D. Evidence for quinone redox chemistry mediating daytime and nighttime NO2-to-HONO conversion on soil surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 9633–9643 (2017).

Stemmler, K., Ammann, M., Donders, C., Kleffmann, J. & George, C. Photosensitized reduction of nitrogen dioxide on humic acid as a source of nitrous acid. Nature 440, 195–198 (2006).

Yang, W. & Marr, L. C. Mechanisms by which ambient humidity may affect viruses in aerosols. Appl. Environ. Microb. 78, 6781–6788 (2012).

Raabe, J. et al. PolLux: a new facility for soft X-ray spectromicroscopy at the Swiss Light Source. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79, 113704 (2008).

Huthwelker, T. et al. An in situ cell to study phase transitions in individual aerosol particles on a substrate using scanning transmission X-ray microspectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 113706–113709 (2010).

Steimer, S. S. et al. Shikimic acid ozonolysis kinetics of the transition from liquid aqueous solution to highly viscous glass. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 31101–31109 (2015).

Moffet, R. C., Tivanski, A. V. & Gilles, M. K. in Fundamentals and Applications of Aerosol Spectroscopy (eds Signorell, R. & Reid, J.) Ch. 17 (CRC Press, 2010).

Moffet, R. C., Henn, T., Laskin, A. & Gilles, M. K. Automated chemical analysis of internally mixed aerosol particles using X-ray spectromicroscopy at the carbon K-edge. Anal. Chem. 82, 7906–7914 (2010).

Alpert, P. A. et al. Visualizing reaction and diffusion in xanthan gum aerosol particles exposed to ozone. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 20613–20627 (2019).

Zelenay, V., Huthwelker, T., Krepelova, A., Rudich, Y. & Ammann, M. Humidity driven nanoscale chemical separation in complex organic matter. Environ. Chem. 8, 450–460 (2011).

Zelenay, V. et al. Direct observation of water uptake and release in individual submicrometer sized ammonium sulfate and ammonium sulfate/adipic acid particles using X-ray microspectroscopy. J. Aerosol Sci. 42, 38–51 (2011).

O’Brien, R. E. et al. Physical properties of ambient and laboratory-generated secondary organic aerosol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2014GL060219 (2014).

O’Brien, R. E. et al. Liquid–liquid phase separation in aerosol particles: imaging at the nanometer scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4995–5002 (2015).

O’Brien, R. E. et al. Chemical imaging of ambient aerosol particles: observational constraints on mixing state parameterization. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 9591–9605 (2015).

Dou, J. et al. Carbon dioxide diffusivity in single, levitated organic aerosol particles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 4484–4489 (2019).

Corral Arroyo, P., Aellig, R., Alpert, P. A., Volkamer, R. & Ammann, M. Halogen activation and radical cycling initiated by imidazole-2-carboxaldehyde photochemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 10817–10828 (2019).

González Palacios, L. et al. Heterogeneous photochemistry of imidazole-2-carboxaldehyde: HO2 radical formation and aerosol growth. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 11823–11836 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grants 163074 and 188662) and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement (No 701647). The PolLux end station was financed by the German Ministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through contracts 05K16WED and 05K19WE2. We acknowledge Mirko Holler for building the UV LED and fiber optic coupling. We further acknowledge Simone Finizio, Katharina Witte, and Blagoj Sarafimov for support at the PolLux end station.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A.A. wrote the manuscript. M.A. and U.K.K. conceptualized and planned the study. P.A.A. planned and conducted STXM/NEXAFS experiments supervised by B.W. and M.A. J.D., P.C.A., J.X., T.H., C.N.B., and K.D.H. also conducted STXM/NEXAFS experiments. P.A.A. conducted STXM/NEXAFS data analysis and interpretation and developed the UV-LED fiber optic setup at the PolLux end station supervised by B.W. and J.R. J.D. conducted EDB experiments and data analysis and interpretation supervised by U.K.K. and T.P. P.C.A conducted CWFT experiments and data analysis and interpretation supervised by M.A. F.S. conducted viscosity experiments and data analysis and interpretation supervised by P.A.A. B.L. wrote and developed the PRAD model with the assistance of J.D. and P.A.A. H.H. and T.S. advised on the photochemical reaction mechanisms. All co-authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript and Supplementary Information.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alpert, P.A., Dou, J., Corral Arroyo, P. et al. Photolytic radical persistence due to anoxia in viscous aerosol particles. Nat Commun 12, 1769 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21913-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21913-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.