Abstract

Background

Anticholinergic medications are commonly prescribed to older adults despite their unfavourable pharmacological profile. There are no specific systems in place to alert prescribers about the wide range of medications with anticholinergic properties and their cumulative potential.

Aims

To examine associations between medications with anticholinergic properties and cognitive and functional impairment in hospitalised patients aged 65 years and older.

Methods

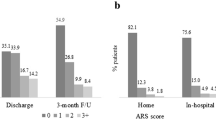

This descriptive, cross-sectional study included 94 patients admitted to a rehabilitation ward and a geriatric evaluation and management unit. Anticholinergic burden was calculated using the Anticholinergic Risk Scale. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination and the Elderly Symptom Assessment Scale tools were utilised to assess cognitive function and burden of anticholinergic symptoms, respectively.

Results

Medications with anticholinergic properties were taken by 72.3% of patients with level 1 being the most commonly consumed (median 1, IQR = 0–2) medications. There was no association between anticholinergic medication use and cognitive function or anticholinergic symptoms. Increasing age and the hospital length of stay were associated with fewer anticholinergic symptoms (p < 0.001 and p = 0.021, respectively), whereas the total number of medications consumed was linked to a greater burden of anticholinergic symptoms (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

A lack of association between anticholinergic medications and cognitive function could be related to duration of exposure to this group of medications and the age sensitivity. Additionally, the total number of medications consumed by patients was linked to a greater burden of anticholinergic symptoms. These findings highlight the need for improved knowledge and attentiveness when prescribing medications in general in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mc Namara KP, Breken BD, Alzubaidi HT et al (2017) Health professional perspectives on the management of multimorbidity and polypharmacy for older patients in Australia. Age Ageing 46:291–299

Morgan TK, Williamson M, Pirotta M et al (2012) A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour snapshot of Australians aged 50 years and older. Med J Aust 196:50–53

Scott IA, Anderson K, Freeman CR et al (2014) First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust 201:390–392

Green AR, Reifler LM, Boyd CM et al (2018) medication profiles of patients with cognitive impairment and high anticholinergic burden. Drugs Aging 35:223–232

Mintzer J, Burns A (2000) Anticholinergic side-effects of drugs in elderly people. J R Soc Med 93:457–462

McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG (2004) Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 56:163–184

Gibson W, Wagg A (2017) Incontinence in the elderly, ‘normal’ ageing, or unaddressed pathology? Nat Rev Urol 14:440–448

Tsakiris P, Oelke M, Michel MC (2008) Drug-induced urinary incontinence. Drugs Aging 25:541–549

Kusljic S, Perera S, Manias E (2018) Age-dependent physiological changes, medicines and sex-influenced types of falls. Exp Aging Res 44:221–231

Bostock CV, Soiza RL, Mangoni AA (2010) Association between prescribing of antimuscarinic drugs and antimuscarinic adverse effects in older people. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 3:441–452

Fox C, Richardson K, Maidment ID et al (2011) Anticholinergic medication use and cognitive impairment in the older population: the medical research council cognitive function and ageing study. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:1477–1483

Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R et al (2007) Anticholinergic drugs and physical function among frail elderly population. Clin Pharmacol Ther 81:235–241

Tay HS, Soiza RL, Mangoni AA (2014) Minimizing anticholinergic drug prescribing in older hospitalized patients: a full audit cycle. Ther Adv Drug Saf 5:121–128

Bali V, Chatterjee S, Johnson ML et al (2016) Risk of cognitive decline associated with paroxetine use in elderly nursing home patients with depression. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 31:678–686

Chatterjee S, Bali V, Carnahan RM et al (2016) Anticholinergic medication use and risk of fracture in elderly adults with depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:1492–1497

Chatterjee S, Bali V, Carnahan RM et al (2016) Anticholinergic medication use and risk of dementia among elderly nursing home residents with depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24:485–495

Campbell N, Boustani M, Limbil T et al (2009) The cognitive impact of anticholinergics: a clinical review. Clin Interv Aging 4:225–233

Lampela P, Lavikainen P, Garcia-Horsman JA (2013) Anticholinergic drug use, serum anticholinergic activity, and adverse drug events among older people: a population-based study. Drugs Aging 30:321–330

Delbaere K, Kochan NA, Close JC et al (2012) Mild cognitive impairment as a predictor of falls in community-dwelling older people. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 20:845–853

Nishtala PS, Fois RA, McLachlan AJ et al (2009) Anticholinergic activity of commonly prescribed medications and neuropsychiatric adverse events in older people. J Clin Pharmacol 49:1176–1184

Sittironnarit G, Ames D, Bush AI et al (2011) Effects of anticholinergic drugs on cognitive function in older Australians: results from the AIBL study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 31:173–178

Naples JG, Marcum ZA, Perera S et al (2015) Concordance between anticholinergic burden scales. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:2120–2124

Tune L, Coyle JT (1980) Serum levels of anticholinergic drugs in treatment of acute extrapyramidal side effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 37:293–297

Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ et al (2006) The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol 46:1481–1486

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC et al (2008) The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med 168:508–513

Ancelin ML, Artero S, Portet F et al (2006) Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 332:455–459

Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Kirshner M et al (2003) Serum anticholinergic activity in a community-based sample of older adults: relationship with cognitive performance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:198–203

Uusvaara J, Pitkala KH, Kautiainen H et al (2011) Association of anticholinergic drugs with hospitalization and mortality among older cardiovascular patients: a prospective study. Drugs Aging 28:131–138

Uusvaara J, Pitkala KH, Tienari PJ et al (2009) Association between anticholinergic drugs and apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele and poorer cognitive function in older cardiovascular patients: a cross-sectional study. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:427–431

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Hartikainen S et al (2014) Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a national population cohort study. PLoS One 9:e83224

Mangoni AA, van Munster BC, Woodman RJ et al (2013) Measures of anticholinergic drug exposure, serum anticholinergic activity, and all-cause postdischarge mortality in older hospitalized patients with hip fractures. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 21:785–793

Pasina L, Djade CD, Lucca U et al (2013) Association of anticholinergic burden with cognitive and functional status in a cohort of hospitalized elderly: comparison of the anticholinergic cognitive burden scale and anticholinergic risk scale: results from the REPOSI study. Drugs Aging 30:103–112

Ahmed S, de Jager C, Wilcock G (2012) A comparison of screening tools for the assessment of mild cognitive impairment: preliminary findings. Neurocase 18:336–351

Saka E, Mihci E, Topcuoglu MA et al (2006) Enhanced cued recall has a high utility as a screening test in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in Turkish people. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 21:745–751

Slavin MJ, Sandstrom CK, Tran TT et al (2007) Hippocampal volume and the mini-mental state examination in the diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188:1404–1410

Ness J, Hoth A, Barnett MJ et al (2006) Anticholinergic medications in community-dwelling older veterans: prevalence of anticholinergic symptoms, symptom burden, and adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 4:42–51

Kouladjian O’Donnell L, Gnjidic D, Nahas R et al (2017) Anticholinergic burden: considerations for older adults. J Pharm Pract Res 47:67–77

Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J et al (2006) The Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 21:1078–1085

Allam M, Fahmy E, Elatti SA et al (2013) Association between total plasma homocysteine level and cognitive functions in elderly Egyptian subjects. J Neurol Sci 332:86–91

Hartley P, Gibbins N, Saunders A et al (2017) The association between cognitive impairment and functional outcome in hospitalised older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 46:559–567

Wouters H, Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D et al (2019) Long-term exposure to anticholinergic and sedative medications and cognitive and physical function in later life. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz019

Whalley LJ, Sharma S, Fox HC et al (2012) Anticholinergic drugs in late life: adverse effects on cognition but not on progress to dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 30:253–261

Risacher SL, McDonald BC, Tallman EF et al (2016) Association between anticholinergic medication use and cognition, brain metabolism, and brain atrophy in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurol 73:721–732

Chrischilles E, Rubenstein L, Van Gilder R et al (2007) Risk factors for adverse drug events in older adults with mobility limitations in the community setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:29–34

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR et al (2004) Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:1349–1354

Campanelli CM (2012) American Geriatrics Society updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: the American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:616

The American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P (2019) American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS beers criteria(R) for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 67:674–694

van Eijk ME, Avorn J, Porsius AJ et al (2001) Reducing prescribing of highly anticholinergic antidepressants for elderly people: randomised trial of group versus individual academic detailing. BMJ 322:654–657

Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C (2007) The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 30:123–152

Wolk DA, Signoff ED, Dekosky ST (2008) Recollection and familiarity in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a global decline in recognition memory. Neuropsychologia 46:1965–1978

Light LL, Patterson MM, Chung C et al (2004) Effects of repetition and response deadline on associative recognition in young and older adults. Mem Cognit 32:1182–1193

Davidson PS, Glisky EL (2002) Neuropsychological correlates of recollection and familiarity in normal aging. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2:174–186

Parkin AJ, Walter BM (1992) Recollective experience, normal aging, and frontal dysfunction. Psychol Aging 7:290–298

Reeve E, Moriarty F, Nahas R et al (2018) A narrative review of the safety concerns of deprescribing in older adults and strategies to mitigate potential harms. Expert Opin Drug Saf 17:39–49

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were approved by the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee and were in accordance with The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007, Australia and its later updates (2015 and 2018).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in this study prior to any data collection.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kusljic, S., Woolley, A., Lowe, M. et al. How do cognitive and functional impairment relate to the use of anticholinergic medications in hospitalised patients aged 65 years and over?. Aging Clin Exp Res 32, 423–431 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01225-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01225-3