Abstract

Background

There is much interest from stakeholders in understanding how health technology assessment (HTA) committees make national funding decisions for health technologies. A growing literature has analysed past decisions by committees (revealed preference, RP studies) and hypothetical decisions by committee members (stated preference, SP studies) to identify factors influencing decisions and assess their importance.

Objectives

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to provide insight into committee preferences for these factors (after controlling for other factors) and the methods used to elicit them.

Methods

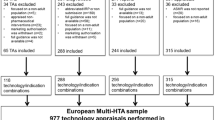

Ovid Medline, Embase, Econlit and Web of Science were searched from inception to 11 May 2017. Included studies had to have investigated factors considered by HTA committees and to have conducted multivariate analysis to identify the effect of each factor on funding decisions. Factors were classified as being important based on statistical significance, and their impact on decisions was compared using marginal effects.

Results

Twenty-three RP and four SP studies (containing 42 analyses) of 14 HTA committees met the inclusion criteria. Although factors were defined differently, the SP literature generally found clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness and equity factors (such as disease severity) were each important to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. These findings were supported by the RP studies of the PBAC, but not the other committees, which found funding decisions by these and other committees were mostly influenced by the acceptance of the clinical evidence and, where applicable, cost-effectiveness. Trust in the evidence was very important for decision makers, equivalent to reducing the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (cost per quality-adjusted life-year) by A$38,000 (Australian dollars) for the PBAC and £15,000 for NICE.

Conclusions

This review found trust in the clinical evidence and, where applicable, cost-effectiveness were important for decision makers. Many methodological differences likely contributed to the diversity in some of the other findings across studies of the same committee. Further work is needed to better understand how competing factors are valued by different HTA committees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Univariate analyses were excluded because they do not account for confounding effects of other factors which may lead to biased results. For example, given cancer drugs are generally more expensive than non-cancer drugs and more expensive drugs are less likely to be funded than less expensive drugs, a univariate analysis may find that cancer drugs are less likely to be funded than non-cancer drugs. However, this may not be the case if the analysis also controls for drug costs.

For example, in a logistic model without interaction terms, the change in probability of a positive recommendation from a reference point \(\Delta P_{j} = \frac{1}{{1 + e^{{ - \left( {L + \beta_{j} } \right)}} }} - P_{\text{ref}} ,\quad {\text{where}}\quad L = \ln \left( {\frac{{P_{\text{ref}} }}{{1 - P_{\text{ref}} }}} \right).\)

A number of these used ICERs sourced from the literature rather than ICERs considered by the committees. However, none of these studies did so due to confidentiality issues. These studies were exploratory in nature and did not investigate the impact of evidence considered on funding decisions. In one study [18], the committee under consideration does not assess cost-effectiveness and hence no ‘official’ ICER existed. In the other studies [17, 19], ‘current funding status’ of health technologies was investigated. However, ‘current funding status’ is not equivalent to a past funding decision, given technologies which are not currently funded may never have been considered by a committee. None of the data used in those studies were sourced from committee documents.

Variables were commonly defined on the basis of an interpretation of the source data by researchers rather than an explicit classification by the committee. Such variables were considered to be defined in an ex-post fashion, or after the fact, and may not have been directly considered by the committee.

References

Drummond M. Twenty years of using economic evaluations for drug reimbursement decisions: what has been achieved? J Health Polit Policy Law. 2013;38(6):1081–102.

Gu Y, Lancsar E, Ghijben P, Butler JR, Donaldson C. Attributes and weights in health care priority setting: a systematic review of what counts and to what extent. Soc Sci Med. 2015;146:41–52.

Dolan P, Shaw R, Tsuchiya A, Williams A. QALY maximisation and people’s preferences: a methodological review of the literature. Health Econ. 2005;14(2):197–208.

Vuorenkoski L, Toiviainen H, Hemminki E. Decision-making in priority setting for medicines—a review of empirical studies. Health Policy. 2008;86(1):1–9.

Stafinski T, Menon D, Philippon DJ, McCabe C. Health technology funding decision-making processes around the world. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(6):475–95.

Erntoft S. Pharmaceutical priority setting and the use of health economic evaluations: a systematic literature review. Value Health. 2011;14(4):587–99.

Niessen LW, Bridges J, Lau BD, Wilson RF, Sharma R, Walker DG, et al. Assessing the impact of economic evidence on policymakers in health care—a systematic review. 2012.

Fischer KE. A systematic review of coverage decision-making on health technologies—evidence from the real world. Health Policy. 2012;107(2):218–30.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Clark S, Weale A. Social values in health priority setting: a conceptual framework. J Health Org Manag. 2012;26(3):293–316.

Rotter JS, Foerster D, Bridges JF. The changing role of economic evaluation in valuing medical technologies. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):711–23.

Guindo LA, Wagner M, Baltussen R, Rindress D, van Til J, Kind P, et al. From efficacy to equity: literature review of decision criteria for resource allocation and healthcare decisionmaking. Cost Effect Resour Allocat. 2012;10(1):9.

Kaufman RL. Comparing effects in dichotomous logistic regression: a variety of standardized coefficients. Soc Sci Quart 1996;90–109.

OECD Data. 2016; Available from: https://data.oecd.org/.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Wiley; 2011.

Anis AH, Guh D, Wang X-H. A dog’s breakfast: prescription drug coverage varies widely across Canada. Med Care. 2001;39(4):315–26.

Segal L, Dalziel K, Mortimer D. Fixing the game: are between-silo differences in funding arrangements handicapping some interventions and giving others a head-start? Health Econ. 2010;19(4):449–65.

Chambers JD, Morris S, Neumann PJ, Buxton MJ. Factors predicting medicare national coverage: an empirical analysis. Med Care. 2012;50(3):249–56.

Schilling C, Mortimer D, Dalziel K. Using CART to Identify thresholds and hierarchies in the determinants of funding decisions. Med Decis Making. 2016:0272989X16638846.

Al MJ, Feenstra T, Brouwer WB. Decision makers’ views on health care objectives and budget constraints: results from a pilot study. Health Policy. 2004;70(1):33–48.

Koopmanschap MA, Stolk EA, Koolman X. Dear policy maker: have you made up your mind? A discrete choice experiment among policy makers and other health professionals. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2010;26(02):198–204.

Lee H-J, Bae E-Y. Eliciting preferences for medical devices in South Korea: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy. 2017;121(3):243–9.

Harris AH, Hill SR, Chin G, Li JJ, Walkom E. The role of value for money in public insurance coverage decisions for drugs in Australia: a retrospective analysis 1994–2004. Med Decis Making. 2008.

Chim L, Kelly PJ, Salkeld G, Stockler MR. Are cancer drugs less likely to be recommended for listing by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia? Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(6):463–75.

Mauskopf J, Chirila C, Masaquel C, Boye KS, Bowman L, Birt J, et al. Relationship between financial impact and coverage of drugs in Australia. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(01):92–100.

Harris A, Li JJ, Yong K. What can we expect from value-based funding of medicines? A retrospective study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(4):393–402.

Karikios DJ, Chim L, Martin A, Nagrial A, Howard K, Salkeld G, et al. Is it all about price? Why requests for government subsidy of anticancer drugs were rejected in Australia. Int Med J. 2017;47(4):400–7.

Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ. 2004;13(5):437–52.

Dakin HA, Devlin NJ, Odeyemi IA. “Yes”, “No” or “Yes, but”? Multinomial modelling of NICE decision-making. Health Policy. 2006;77(3):352–67.

Mauskopf J, Chirila C, Birt J, Boye KS, Bowman L. Drug reimbursement recommendations by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: have they impacted the National Health Service budget? Health Policy. 2013;110(1):49–59.

Cerri KH, Knapp M, Fernandez J-L. Decision making by NICE: examining the influences of evidence, process and context. Health Econ Policy Law. 2014;9(02):119–41.

Dakin H, Devlin N, Feng Y, Rice N, O’Neill P, Parkin D. The influence of cost-effectiveness and other factors on nice decisions. Health Econ. 2015;24(10):1256–71.

Linley WG, Hughes DA. Reimbursement decisions of the All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(9):779–94.

Niewada M, Polkowska M, Jakubczyk M, Golicki D. What influences recommendations issued by the agency for health technology assessment in Poland? A glimpse into decision makers’ preferences. Value Health Region Issue. 2013;2(2):267–72.

Rocchi A, Miller E, Hopkins RB, Goeree R. Common drug review recommendations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2012;30(3):229–46.

Chambers JD, Chenoweth M, Cangelosi MJ, Pyo J, Cohen JT, Neumann PJ. Medicare is scrutinizing evidence more tightly for national coverage determinations. Health Aff. 2015;34(2):253–60.

Pauwels K, Huys I, De Nys K, Casteels M, Simoens S. Predictors for reimbursement of oncology drugs in Belgium between 2002 and 2013. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(5):859–68.

Le Pen C, Priol G, Lilliu H. What criteria for pharmaceuticals reimbursement? Eur J Health Econ. 2003;4(1):30–6.

Cerri KH, Knapp M, Fernandez J-L. Public funding of pharmaceuticals in the Netherlands: investigating the effect of evidence, process and context on CVZ decision-making. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(7):681–95.

Park SE, Lim SH, Choi HW, Lee SM, Kim DW, Yim EY, et al. Evaluation on the first 2 years of the positive list system in South Korea. Health Policy. 2012;104(1):32–9.

Kim E-S, Kim J-A, Lee E-K. National reimbursement listing determinants of new cancer drugs: a retrospective analysis of 58 cancer treatment appraisals in 2007–2016 in South Korea. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017 (just-accepted).

Schmitz S, McCullagh L, Adams R, Barry M, Walsh C. Identifying and revealing the importance of decision-making criteria for health technology assessment: a retrospective analysis of reimbursement recommendations in Ireland. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(9):925–37.

Charokopou M, Majer IM, de Raad J, Broekhuizen S, Postma M, Heeg B. Which factors enhance positive drug reimbursement recommendation in Scotland? A retrospective analysis 2006–2013. Value Health. 2015;18(2):284–91.

Svensson M, Nilsson FO, Arnberg K. Reimbursement decisions for pharmaceuticals in Sweden: the impact of disease severity and cost effectiveness. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(11):1229–36.

Cerri KH, Knapp M, Fernandez J-L. Untangling the complexity of funding recommendations: a comparative analysis of health technology assessment outcomes in four European countries. Pharm Med. 2015;29(6):341–59.

Whitty JA, Scuffham PA, Rundle-Thielee SR. Public and decision maker stated preferences for pharmaceutical subsidy decisions. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(2):73–9.

Tappenden P, Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Chilcott J. A stated preference binary choice experiment to explore NICE decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(8):685–93.

Linley WG, Hughes DA. Decision-makers’ preferences for approving new medicines in Wales: a discrete-choice experiment with assessment of external validity. Pharmacoeconomics. 2013;31(4):345–55.

Skedgel C. The prioritization preferences of pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review members and the Canadian public: a stated-preferences comparison. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(5):322.

ISPOR Global Health Care Systems Road Map. 2016; Available from: http://www.ispor.org/htaroadmaps/france.asp.

Bach F. Model-consistent sparse estimation through the bootstrap. arXiv preprint arXiv:09013202. 2009.

Social value judgements: principles for the development of NICE guidance, 2nd edn: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

Guidelines for the pharmaceutical industry on preparations of submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2002.

Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (Version 4.0). Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2006.

Fischer KE, Leidl R. Analysing coverage decision-making: opening Pandora’s box? Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(9):899–906.

Franken M, Stolk E, Scharringhausen T, de Boer A, Koopmanschap M. A comparative study of the role of disease severity in drug reimbursement decision making in four European countries. Health Policy. 2015;119(2):195–202.

Gulácsi L, Rotar AM, Niewada M, Löblová O, Rencz F, Petrova G, et al. Health technology assessment in Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(1):13–25.

Stafinski T, Menon D, Davis C, McCabe C. Role of centralized review processes for making reimbursement decisions on new health technologies in Europe. Clin Econ Outcomes Res CEOR. 2011;3:117.

Franken M, le Polain M, Cleemput I, Koopmanschap M. Similarities and differences between five European drug reimbursement systems. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;28(4):349–57.

ISPOR Initiative on US Value Assessment Frameworks. 2017; Available from: https://www.ispor.org/ValueAssessmentFrameworks/Index.

Kaló Z, Gheorghe A, Huic M, Csanádi M, Kristensen FB. HTA implementation roadmap in Central and Eastern European countries. Health Econ. 2016;25(S1):179–92.

Robertson J, Walkom EJ, Henry DA. Transparency in pricing arrangements for medicines listed on the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Aust Health Rev. 2009;33(2):192–9.

Lexchin J. Coverage with evidence development for pharmaceuticals: a policy in evolution? Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(2):337–54.

Parkinson B, Sermet C, Clement F, Crausaz S, Godman B, Garner S, et al. Disinvestment and value-based purchasing strategies for pharmaceuticals: an international review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(9):905–24.

Acknowledgements

The author team would like to thank Dennis Petrie for his helpful suggestions and valuable advice in drafting the review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the systematic review. PG and YG applied the selection criteria to the identified studies; EL adjudicated any differences. PG and SZ extracted and synthesised the data. PG drafted the manuscript, with input from the other authors. PG acts as guarantor for the paper and accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the review and decision to publish.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The research was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (APP1047788): “Societal and decision maker preferences for priority setting in health care resource allocation”.

Conflict of interest

EL declares no conflict of interest. PG, YG and SZ declare they are contracted through their respective universities to evaluate submissions for listing of pharmaceuticals on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in Australia. Neither they nor their spouses, partners or children have any other financial or non-financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work. The content of this paper does not reflect the views of the Australian Government Department of Health, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee or its sub-committees.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no datasets were generated or analysed. All findings were based on the published studies included in this review.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghijben, P., Gu, Y., Lancsar, E. et al. Revealed and Stated Preferences of Decision Makers for Priority Setting in Health Technology Assessment: A Systematic Review. PharmacoEconomics 36, 323–340 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0586-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0586-1