Abstract

Introduction

Premixed insulin analogs represent an alternative to basal or basal–bolus insulin regimens for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D). “Low-mix” formulations with a low rapid-acting to long-acting analog ratio (e.g., 25/75) are commonly used, but 50/50 formulations (Mix50) may be more appropriate for some patients. We conducted a systematic literature review to assess the efficacy and safety of Mix50, compared with low-mix, basal, or basal–bolus therapy, for insulin initiation and intensification.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ClinicalTrials.gov, LillyTrials.com, and NovoNordisk-trials.com were searched (11 or 13 Dec 2016) using terms for T2D, premixed insulin analogs, and/or Mix50. Studies (randomized, nonrandomized, or observational; English only) comparing Mix50 with other insulins (except human) and reporting key efficacy [glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting and postprandial glucose] and/or safety (hypoglycemia, weight gain) outcomes were eligible for inclusion. Narrative reviews, letters, editorials, and conference abstracts were excluded. Risk of bias in randomized trials was assessed using the Cochrane tool.

Results

MEDLINE and EMBASE searches identified 716 unique studies, of which 32 met inclusion criteria. An additional three studies were identified in the other databases. All 19 randomized trials except one were open label; risk of other biases was generally low. Although not conclusive, the evidence suggests that Mix50 may provide better glycemic control (HbA1c reduction) and, particularly, postprandial glucose reduction in certain patients, such as those with high carbohydrate diets and Asian patients, than low-mix and basal therapy. Based on this evidence and our experience, we provide clinical guidance on factors to consider when deciding whether Mix50 is appropriate for individual patients.

Conclusions

Mix50 may be more suitable than low-mix therapy for certain patients. Clinicians should consider not only efficacy and safety but also patient characteristics and preferences when tailoring insulin treatment to individuals with T2D.

Funding

Eli Lilly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The progressive nature of type 2 diabetes (T2D) requires continual monitoring and frequent treatment adjustment [1,2,3,4,5,6]. To minimize the adverse consequences of prolonged hyperglycemia, people with T2D are treated to reach individualized glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) targets (often < 6.5% or < 7% (< 48 or < 53 mmol/mol) [2,3,4,5]). If HbA1c targets cannot be attained with non-insulin treatments, insulin should be initiated to replace or supplement other therapies.

Most international guidelines recommend that people with T2D initiate insulin with basal therapy, e.g., once-daily insulin glargine or neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH), with or without concomitant oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Some guidelines suggest premixed insulin analogs, i.e., mixtures of a rapid-acting insulin analog and a long-acting protamine suspension of that analog, as an alternative to initiation with basal insulin [3, 4, 6]. The most commonly used premixed insulin analogs have a low ratio of rapid-acting to long-acting insulin analog (“low mix”), such as 25% insulin lispro, 75% insulin lispro protamine (Lispro 25; Humalog® Mix25™ or Mix75/25™; Eli Lilly and Company) or 30% rapid-acting insulin aspart, 70% long-acting insulin aspart (biphasic insulin aspart 30 [BIAsp30]; NovoMix® 30; Novo Nordisk). However, formulations with equal proportions (“mid mix” or Mix50) of rapid- and long-acting insulin lispro (Lispro 50; Humalog® Mix50™ or Mix50/50™; Eli Lilly and Company) or insulin aspart (BIAsp50; NovoMix® 50; Novo Nordisk) are also available, as is a “high-mix” formulation with 70% rapid-acting, 30% long-acting insulin aspart (BIAsp70; NovoMix® 70; Novo Nordisk). Premixed insulins, when given before meals, have the advantage of targeting both fasting and postprandial glucose levels with a single injection.

Intensification of insulin therapy should be considered for patients who do not reach HbA1c targets on once-daily basal or premixed analog therapy. The most common approach to intensification is basal–bolus therapy, in which prandial injections of rapid-acting insulin are added to basal therapy. Premixed insulin analogs can be employed for intensification by using two or, occasionally, three injections before meals. Regimens based on premixed analogs can be simpler than basal–bolus regimens, as the patient only requires one type of injection device. Conversely, basal–bolus regimens offer greater flexibility than premixed analogs. Most treatment guidelines suggest that both basal–bolus and premixed insulin analogs are appropriate options for intensification [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, these guidelines do not provide advice regarding the choice of premixed ratio (i.e., low, mid, or high mix).

Several groups have published clinical guidance on the use of low-mix insulin analogs [7, 8]. However, to our knowledge, only one group has made clinical recommendations on the use of mid-mix (or high-mix) premixed analogs [9]. These recommendations, published in 2011 as part of a consensus statement, rely on clinical evidence from just four studies [9]. Thus, recent evidence-based guidance on the use of Mix50 is lacking. Further, Mix50 may be more appropriate than other insulin therapy options for certain patients, such as those with high carbohydrate diets who require greater control of postprandial glucose. We therefore conducted a systematic review to assess the current evidence of the efficacy and safety of Mix50, compared with low-mix analogs, basal therapy, and basal–bolus therapy, for people with T2D requiring insulin initiation or intensification. Based on this evidence and our experience, we provide clinical recommendations and practical guidance on the use of Mix50.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

The following online databases were searched on 11 or 13 December 2016: MEDLINE via PubMed; EMBASE via Ovid; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; ClinicalTrials.gov results database; LillyTrials.com; and NovoNordisk-trials.com. Search terms were optimized for each database. For MEDLINE, the search comprised “(diabetes mellitus, type 2 OR type 2 diabetes OR type II diabetes OR non-insulin dependent diabetes OR NIDDM) AND (insulin lispro OR insulin aspart OR biphasic insulins) AND (mix* OR premix* OR 50/50),” where asterisk indicates truncation. For EMBASE, the search comprised “(non insulin dependent diabetes OR diabetes mellitus, type 2 OR type 2 diabetes OR type II diabetes OR non-insulin dependent diabetes OR NIDDM) AND (insulin lispro OR insulin aspart) AND (mix* OR premix* OR 50/50).” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ClinicalTrials.gov (restricted to trials with study results posted), LillyTrials.com, and NovoNordisk-trials.com sites were searched using “(insulin lispro OR insulin aspart).” Relevant studies were cross-checked against MEDLINE and EMBASE results to identify duplicate studies. All searches were restricted to reports in the English language only; there was no restriction on publication date.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Studies were considered for inclusion if they involved adults (≥ 18 years) with T2D who were treated with Mix50 in any regimen as initiation or intensification. Studies that compared Mix50 with any other insulin therapy, except human insulins, were eligible; although basal and premixed human insulins are still available, they are not commonly used in current clinical practice and have different pharmacokinetic profiles compared with analogs [1, 10]. Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized clinical trials, and prospective and retrospective observational studies were eligible for inclusion; narrative reviews, letters, editorials, commentaries, and conference abstracts were excluded.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported any of the following outcomes: change from baseline (or end point levels) in HbA1c, fasting blood (FBG) or plasma (FPG) glucose, postprandial blood or plasma glucose (PPG), or self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG); proportion of patients achieving HbA1c targets; incidence of hypoglycemia; weight gain; patient-reported outcomes (e.g., quality of life, treatment satisfaction); or adherence.

Study Selection

The output from the MEDLINE and EMBASE searches was imported into a reference manager and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria for potential eligibility. A subset of articles required review of the full text to establish eligibility. Studies identified in the other databases were compared against eligible studies identified in the MEDLINE and EMBASE database searches and duplicates removed. The bibliographies of relevant systematic reviews were manually screened for additional articles. Searches and screening were performed by a contracted medical writer using a search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria developed and approved by three of the authors (GD, GK, TW). All authors agreed on the final studies for inclusion.

Data Extraction

Data relevant to the prespecified outcomes listed above were extracted into standardized data tables. Data extracted included article citation, country/region, sponsor, study design, duration, patient eligibility criteria, number of patients enrolled and completed, treatment regimens, efficacy outcomes, safety outcomes, and patient-reported outcomes. For presentation and interpretation of results, studies were grouped by whether Mix50 was used for initiation or intensification and by whether Mix50 was compared with low-mix insulin analogs, basal insulin, or basal–bolus regimens, resulting in six main sets of studies.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias was assessed for RCTs using the Cochrane Collaboration tool [11]. The risk of bias for nonrandomized studies was not formally assessed, but the inherent biases associated with these studies were acknowledged.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Literature Search Results

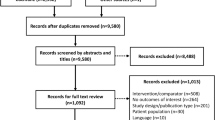

A total of 915 articles were retrieved from MEDLINE (n = 214) and EMBASE (n = 701) (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 716 articles were screened. Of these, 684 articles were excluded, most commonly because they did not include data on Mix50 or they were the wrong type of publication (e.g., narrative review article). There were 32 articles that met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review. Searching the other databases identified three additional, unpublished studies that met the eligibility criteria, for a total of 35 included articles or studies (hereafter referred to simply as “studies”) (Fig. 1; Table S1 in the Electronic supplementary material, ESM).

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 35 studies, there were two systematic reviews or meta-analyses [12, 13], 19 RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] (including three crossover studies [19, 25, 28]), two post hoc analyses of pooled data from RCTs [33, 34], ten prospective, nonrandomized, observational or interventional studies [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], one retrospective observational study [45], and one consensus statement [9] (Table S1 in the ESM). Sample sizes ranged from 13 [42] to 744 [23]; overall, the studies enrolled more than 6000 patients. The studies were conducted in a broad range of countries from North America, South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Nine studies examined Mix50 for insulin initiation [14, 16, 18,19,20, 22, 29, 31, 32] (Table 1), and 13 studies examined Mix50 for intensification [15, 17, 21, 23,24,25,26,27, 34, 36, 40,41,42] (Table 2). The remaining 13 studies were not included in these sets for reasons such as combining initiation and intensification or not comparing Mix50 with other insulins [9, 12, 13, 28, 30, 33, 35, 37,38,39, 43,44,45] (Table 3). There were no reports of patient adherence with Mix50.

Risk of Bias

Because all RCTs (and post hoc analyses of RCTs) except one [28] were open label, we classified the risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel as high (Table 4). However, open-label RCTs are an accepted study design in insulin trials because of the need for dose titration to minimize hypoglycemia. Information on random sequence generation and allocation concealment was lacking in 8 of the 21 RCTs or post hoc analyses, and information regarding preplanned study outcomes, which could be used to detect potential selective outcome reporting, was lacking in 11 of the 21 studies. In these cases, we classified the risk of these types of bias as “unclear.” For objective outcome measures such as HbA1c and glucose levels, we considered the risk of bias due to inadequate blinding of assessors as low for most RCTs; however, we recognize that the risk of bias associated with an open-label study is high for certain, patient-reported outcomes, such as undocumented (i.e., self-reported) symptomatic hypoglycemia and quality of life measures. Patients also reported their own diets in the subanalysis by Chen et al. [14] and ethnicities in the post hoc analysis by Davidson et al. [33], which may have affected the subgroup comparisons of HbA1c. Therefore, we classified the blinding of outcome assessors for these two studies as “unclear.” Finally, we considered the risk of selective reporting bias as high for the two pooled analyses because of their post hoc nature [33, 34].

Initiation

Mix50 vs. Low-Mix Insulin Analogs (5 Studies)

Five studies (all RCTs; two were subgroup analyses [14, 29] of one RCT [31]) compared Lispro 50 (total 305 patients) with low-mix insulin analogs (total 316 patients) in insulin-naive patients poorly controlled on OHAs [14, 16, 29, 31, 32] (Table 1; Table S1 in the ESM). Four of these studies compared Lispro 50 twice daily (BID) with Lispro 25 BID [14, 29, 31, 32]; one study compared Lispro 50 with BIAsp30 at 1 to 3 injections per day for each treatment [16]. Treatment duration ranged from 12 [32] to 48 weeks [16]. All studies were conducted in Asia (primarily Japan and China).

Lispro 50 resulted in a greater reduction in HbA1c levels compared with low-mix, although the difference was statistically significant in only two studies [29, 32] (Fig. 2; Table 1). The mean change from baseline in HbA1c with Lispro 50 ranged from − 1.69% [31] to − 4.2% [32] (Fig. 2). In subgroup analyses of one RCT, Lispro 50 was more effective than Lispro 25 at reducing HbA1c among patients with baseline HbA1c, PPG, FPG, or glucose excursions, or carbohydrate, fat, or protein intake, greater than the median level, and in patients with energy intake lower than the median [14, 29, 31]. In addition, Lispro 50 was more effective than Lispro 25 in both men and women and in both older (≥ 65 years) and younger (< 65 years) patients [29]. Where reported, the proportion of patients reaching target HbA1c levels was also greater with Lispro 50 than with low-mix [16, 29, 31] (Table S2 in the ESM). There was no consistent effect of Lispro 50 vs. low-mix on fasting glucose levels (Table 1). In contrast, Lispro 50 consistently reduced PPG, glucose excursions, and/or average SMBG levels to a greater extent than low-mix (Table 1; Table S2 in the ESM). There were no reported differences between treatments in total daily insulin dose at end point, incidence or rate of hypoglycemia, or in the amount of weight gained (Table 1; Table S2 in the ESM).

Changes in HbA1c with Mix50 or low-mix insulin analog treatment in studies of initiation (a) or intensification (b). P values shown are comparisons between target groups, where reported. aChange from baseline calculated from baseline and end point values. bSubanalysis of Watada trial. CHO carbohydrate, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, low-mix premixed insulin analog containing 25% or 30% rapid-acting component, LSM least-squares mean, Mix50 premixed insulin analog containing 50% rapid-acting component, ND not determined, NS not significant

Mix50 vs. Basal Insulin (2 Studies)

Two RCTs compared Lispro 50 (with or without one Lispro 25 injection; total 114 patients) with basal insulin (total 113 patients) in insulin-naive patients (Table 1; Table S1 in the ESM) [19, 22]. One RCT was an 8-month crossover study conducted in the United States that compared Lispro 50 before breakfast and lunch plus Lispro 25 before dinner with basal insulin glargine [19]. The other RCT was a 24-week, 3-arm study conducted in Germany that compared Lispro 50 three times daily (TID) with insulin lispro TID and also with basal insulin glargine [22].

In these RCTs, Lispro 50 resulted in a greater reduction in HbA1c levels compared with basal insulin glargine (Table 1). The mean change from baseline in HbA1c with Lispro 50 in each study was − 1.01% [19] and − 1.2% [22]. The proportion of patients reaching target HbA1c levels was numerically but not statistically (or not verified statistically) greater with Lispro 50 than with glargine (Table S2 in the ESM). One RCT showed a greater decrease in FBG with glargine than with Lispro 50 [22], whereas the other RCT showed no significant difference in FBG between treatments [19] (Table 1). In both RCTs, Lispro 50 reduced glucose excursions and post-meal SMBG levels but not PPG (reported in one RCT [22]) to a greater extent than glargine (Table 1; Table S2 in the ESM). The total daily insulin dose at end point and the rate of hypoglycemia were both greater for Lispro 50 than for glargine; weight gain was similar or greater for Lispro 50 than for glargine (Table 1; Table S2 in the ESM).

In one RCT, 63.0% of the 54 patients receiving Lispro 50 and 50.9% of the 53 patients receiving glargine reported their treatment satisfaction (assessed with a nonvalidated, 5-point Likert scale) at the end of the 24-week study as high or very high [22]. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as the treatment satisfaction questionnaire was not a standard validated tool and therefore may not have been reliable. The same study also reported that 83.3% of patients receiving Lispro 50 were willing to continue their current treatment, compared with 77.4% of patients receiving glargine [22].

Mix50 vs. Basal–Bolus (2 studies)

One 36-week RCT [20] and one 48-week RCT [18] compared 1 to 3 injections of Lispro 50 (with or without Lispro 25 injections; total 413 patients) with basal insulin glargine plus 1 or 2 prandial injections of insulin lispro (total 415 patients) in insulin-naive patients (Table 1; Table S1 in the ESM). Both RCTs were multinational and examined specific algorithms for initiating and intensifying insulin, starting with a single injection of Lispro 50 or glargine and progressively adding mealtime injections of Lispro 50 and/or Lispro 25 or insulin lispro, respectively.

In both RCTs, there was no significant difference between Lispro 50 and basal–bolus insulin in the reduction of HbA1c [18, 20] (Table 1). Despite this, in one RCT, noninferiority of Lispro 50 to basal–bolus could not be demonstrated [20]. The mean change from baseline in HbA1c with Lispro 50 in each RCT was − 1.65% [18] and − 1.76% [20]. The proportion of patients reaching HbA1c targets also did not differ between treatments, except that one RCT reported that a greater proportion of patients receiving Lispro 50 reached HbA1c < 7.0% compared with basal–bolus [18] (Table S2 in the ESM). In contrast, another RCT reported that a mean HbA1c < 7.0% was achieved only with thrice-daily basal–bolus therapy and not with once- or twice-daily basal–bolus or with any Lispro 50 regimen [20]. This RCT also reported a higher FBG at end point with Lispro 50 than with basal–bolus [20], whereas the other RCT did not report FBG data [18] (Table 1). There was no consistent effect of Lispro 50 vs. basal–bolus on SMBG levels, including post-meal values (Table S2 in the ESM). The total daily insulin dose at end point was reported in one RCT as greater for Lispro 50 than for basal–bolus [20] (Table S2 in the ESM). There were no significant differences between Lispro 50 and basal–bolus in the incidence or rate of hypoglycemia, or in the amount of weight gained (Table 1). One RCT reported that scores for both the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) and the EuroQol EQ-5D increased significantly from baseline in both treatment groups, but with no reported difference between treatments [18].

Intensification

Mix50 vs. Low-Mix Insulin Analogs (7 Studies)

Four RCTs [15, 17, 24, 25] and three nonrandomized studies [40,41,42] compared Mix50 (total 811 patients) with low-mix insulin analogs (total 828 patients) in patients poorly controlled despite previous treatment with insulin (with or without OHAs) (Table 2; Table S1 in the ESM). In five of these studies, previous treatment consisted of premixed insulin (human or analog, usually low mix). Treatment regimens varied amongst the studies, and treatment duration ranged from 2 days [42] to 36 weeks [15]. The studies were conducted in Europe [15]; Europe, South Africa, and Turkey [17]; China [24]; India [25]; Israel [40]; and Japan [41, 42].

Overall, Mix50 resulted in a greater reduction in HbA1c levels compared with low mix, although the results were not consistent (Fig. 2; Table 2). The treatment difference was statistically significant in two RCTs of BIAsp50 [15, 24], but not in another of Lispro 50 [17]; the fourth RCT of Lispro 50 did not report change from baseline levels, but the end point HbA1c did not differ between groups [25]. The mean change from baseline in HbA1c with Mix50 ranged from − 0.6% [40] to − 1.9% [15]. Similarly, the proportion of patients reaching target HbA1c levels was greater with Mix50 than with low mix in two RCTs of BIAsp50 [15, 24], but not in a third RCT of Lispro 50 [17] (Table S2 in the ESM). There were no differences between Mix50 and low mix in the effect on FPG/FBG, except in one RCT where FPG at end point was significantly higher with Lispro 50 than with low mix [17] (Table 2). In contrast, Mix50 reduced PPG, glucose excursions, and/or average SMBG levels to a greater extent than low mix (Table 2; Table S2 in the ESM). The total daily insulin dose at end point was higher for Mix50 than for low mix in three of the four studies when statistically compared (Table S2 in the ESM). The relative risk of minor hypoglycemia did not differ between Mix50 and low mix in one RCT of BIAsp50 [15]; the rate of nocturnal hypoglycemia was higher with Mix50 than with low mix in one RCT of BIAsp50 [24], but lower in another RCT of Lispro 50 [17]; other studies did not report any significant differences in hypoglycemia between treatment groups (Table 2). Weight gain was significantly higher with Mix50 than with low-mix in one RCT of Lispro 50 [17]; the other studies did not report any statistical differences in weight gain between treatments (Table 2).

Mix50 vs. Basal Insulin (2 Studies)

One multinational, 24-week RCT compared Lispro 50 (n = 158) with basal glargine (n = 159) in patients poorly controlled on insulin (0–2 injections/day) and OHAs [26]; data from this RCT were the only Mix50 data included in a post hoc analysis [34] (Table 2; Table S1 in the ESM). Although this RCT included patients who were insulin-naive, most patients (78.7%; 248 of 315) were on insulin before the trial [26].

Lispro 50 resulted in a greater reduction in HbA1c levels (− 0.72%) compared with basal glargine (− 0.35%) [26, 34] (Table 2). The proportion of patients reaching target HbA1c levels was also statistically greater with Lispro 50 than with glargine [26] (Table S2 in the ESM). There was a greater decrease in FBG, and the end point FBG values were lower, with glargine than with Lispro 50 [26, 34] (Table 2). Conversely, Lispro 50 reduced PPG excursions and SMBG at all time points except at 3 am and pre-breakfast (i.e., FBG) to a greater extent than glargine [26] (Table 2; Table S2 in the ESM). In addition, as demonstrated in the post hoc analysis, Lispro 50 was associated with lower glycemic variability (assessed by 5 indices) than glargine [34] (Table S2 in the ESM). The total daily insulin dose at end point, the rate of hypoglycemia, and the amount of weight gained were greater for Lispro 50 than for glargine (Table 2; Table S2 in the ESM).

Mix50 vs. Basal–Bolus (4 Studies)

Three 24-week RCTs compared Lispro 50 (with or without Lispro 25 injections; total 560 patients) with basal–bolus insulin (basal glargine plus prandial insulin lispro; total 561 patients) in patients poorly controlled on basal or premixed insulin BID with or without OHAs [21, 23, 27] (Table 2; Table S1 in the ESM). One of these RCTs [23] was a multinational substudy of patients who required intensification after 6 months of initial treatment with either basal glargine or Lispro 25 BID [46]. The other RCTs were conducted in Asia (China, Taiwan, Korea) [21] and in the United States and Puerto Rico [27]. An additional 16-week nonrandomized study conducted in Japan examined 28 patients who switched from Mix50 to basal insulin glargine plus insulin glulisine BID [36].

In the RCTs, Lispro 50 reduced HbA1c to a similar [21, 23] or lesser [27] extent than basal–bolus insulin (Table 2). In the nonrandomized study, switching from Mix50 to basal–bolus resulted in a nonsignificant decrease in HbA1c (− 0.1%) [36] (Table 2). The mean change from baseline in HbA1c with Lispro 50 was − 1.1% [21] and − 1.87% [27] in the two RCTs that reported this variable. The proportion of patients reaching target HbA1c levels was lower with Lispro 50 than with basal–bolus insulin, although not all differences were statistically significant (Table S2 in the ESM). Lispro 50 was also less effective than basal–bolus at reducing FBG (Table 2). One RCT reported that Lispro 50 was more effective than basal–bolus at reducing post-lunch PPG, with no treatment differences for blood glucose after other meals [21]; another RCT reported that end point PPG post-breakfast, but not after other meals, was significantly higher with Lispro 50 than with basal–bolus [27] (Table 2). In one RCT, the total daily insulin dose at end point was lower for Lispro 50 than for basal–bolus [27]; there were no treatment group differences in dose in the other RCTs [21, 23] (Table S2 in the ESM). There were no reported differences between Lispro 50 and basal–bolus in the incidence or rate of hypoglycemia, or in the amount of weight gained (Table 2).

In one RCT, there were no differences in the change in DTSQ treatment satisfaction or perceived frequency of hyperglycemia scores (both status and change versions of the DTSQ), or in the Experience With Insulin Therapy Questionnaire (EWITQ) scores, between Lispro 50 (+ Lispro 25) and basal–bolus therapy [21]. However, the DTSQ (status version) perceived frequency of hypoglycemia was significantly higher in the Lispro 50 (+ Lispro 25) group than in the basal–bolus group (P = 0.017) [21]. In the nonrandomized study, there was no significant change in DTSQ treatment satisfaction, perceived hyperglycemia, or perceived hypoglycemia scores after patients switched from Mix50 to basal–bolus [36].

Other Studies (13 Studies)

Although the remaining studies could not be included in the summaries above for various reasons (shown in Table 3), several of these studies are noteworthy. The two systematic reviews combined studies of initiation and studies of intensification [12, 13]. One systematic review [13] conducted a meta-analysis of three RCTs [19, 22, 26], which suggested that Lispro 50 was more efficacious than basal glargine at reducing HbA1c and PPG, but that glargine was more efficacious than Lispro 50 at reducing FBG. This systematic review also concluded that premixed analogs (Lispro 25, BIAsp30, Lispro 50) are associated with a greater incidence of hypoglycemia and more weight gain [13]. The other systematic review supported these general conclusions, although no meta-analysis was conducted [12].

One post hoc analysis that included two RCTs involving Lispro 50 examined the effect of ethnicity on the response to Lispro 50 vs. Lispro 25 vs. combined basal or basal–bolus therapy in patients requiring intensification [33] (Table 3). There was no effect of ethnicity on the efficacy or safety of Lispro 50, except a significantly higher rate of severe hypoglycemia in Asian patients compared with Caucasian patients. The analysis also suggested that Lispro 25 may be less effective at reducing HbA1c in Asian and Latino–Hispanic patients, and basal/basal–bolus therapy more effective in Latino–Hispanic patients, compared with Caucasian patients [33].

A consensus statement published in 2011 presented clinical evidence on the use of BIAsp50 and BIAsp70 in patients currently on BIAsp30 who required intensification [9]. The statement recommended several patient subgroups who may benefit the most from premixed BIAsp with higher ratios of rapid-acting insulin aspart, including: patients poorly controlled on low-mix insulin BID or TID; patients with elevated FPG and PPG levels may benefit most from BIAsp50; and patients with normal FPG but elevated PPG may benefit most from BIAsp70 [9]. The consensus statement also provided specific algorithms and dosing titration schedules for intensification, depending on each patient’s PPG and FPG levels [9].

Strengths and Limitations of This Systematic Review

This review is strengthened by its systematic approach to identifying relevant studies, including unpublished studies, the consideration of Mix50 for both initiation and intensification, the comparison of Mix50 with three other general approaches to insulin therapy (low mix, basal, basal-bolus), the diverse range of countries represented, and the risk of bias assessment. Limitations include heterogeneity in the study designs, populations, treatment regimens, durations, and reported outcomes (including the use of self-reporting of hypoglycemic episodes in most studies), the limited number of studies in some settings or comparisons, and the exclusion of articles not written in English.

Summary of Evidence and Clinical Recommendations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to collate the evidence regarding the relative efficacy and safety of Mix50 as a treatment option for the initiation or intensification of insulin therapy. Overall, the evidence suggests that Mix50 may be more effective in certain patient groups (e.g., those with high-carbohydrate diets, Asian) than low-mix insulin analogs in reducing HbA1c, primarily via reductions in PPG levels, although with a possible increased risk of hypoglycemia. These results indicate that Mix50 represents an alternative treatment option, especially for patients who prefer premixed insulins but require greater glycemic control after meals than that provided by low-mix insulins. In the section below, we provide practical guidance, based on the collected evidence and our clinical expertise, on the use of Mix50 for insulin initiation and intensification. Importantly, treatment decisions should be individualized for the patient, and the broad range of available therapies and regimens enable flexibility to tailor treatment to the patient.

Insulin Initiation with Mix50

Summary of Evidence

For patients initiating insulin treatment, the evidence suggests that Mix50 may result in better glycemic control than either low-mix insulin analogs or basal therapy with insulin glargine, at least in Asian patients with assumed high-carbohydrate diets (Table 1). The improved glycemic control when using Mix50 is undoubtedly related to the greater reduction of PPG levels (Table 1). Although the risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain is somewhat greater with Mix50 than with basal insulin, this is also true with low-mix insulin analogs [12, 13].

Interestingly, the studies comparing Mix50 with low-mix analogs for initiation were all conducted in Asia, where premixed insulins are more commonly used than in Western countries [31, 47]. Asian patients may require tighter control of PPG in part because of a high-carbohydrate diet [14, 31] and because of greater glycemic responses to certain foods like rice compared with patients of European descent [48]. Indeed, subanalyses of the largest RCT indicate that Lispro 50 has the most benefit relative to Lispro 25 in patients with a high carbohydrate intake, as well as in patients with high baseline HbA1c (≥ 8.4%), PPG (≥ 13.30 or ≥ 13.5 mmol/L), glucose excursion (≥ 4.4 mmol/L), or FPG (≥ 9.0 mmol/L), at least in this Asian study population [14, 29, 31]. None of the studies comparing Mix50 with low-mix analogs for initiation were conducted in non-Asian countries; thus, we do not currently know if Mix50 is more effective than low mix in patients of other ethnicities or with different dietary habits.

Identifying Patients Suitable for Initiation with Mix50 (Fig. 3)

Although Mix50 is not commonly used for the initiation of insulin therapy, there are some patients for whom it may be considered. As mentioned above, this includes patients with large PPG excursions (especially after lunch) and those with carbohydrate-rich diets. Even in the absence of a high-carbohydrate diet, patients with high PPG should be considered for Mix50. Decisions on whether Mix50 or low mix is more suitable are best guided by examining matched pre- and postprandial glucose concentrations, together with HbA1c levels. Patients with certain ethnic backgrounds, such as Asian or Pacific Islander, may also benefit from Mix50, either because of their diet or because of underlying physiological differences in the glycemic response to meals [48, 49].

Factors to consider when deciding whether to prescribe Mix50. Arrows indicate which insulin types are more (up arrow) or less (down arrow) suitable for patients with different characteristics. Low-mix premixed insulin analog containing 25% or 30% rapid-acting component, Mix50 premixed insulin analog containing 50% rapid-acting component

The risk of hypoglycemia and the patient’s ability to manage hypoglycemic episodes is also an important consideration. For example, if nocturnal hypoglycemia is a potential issue, Mix50 at dinner may be a better choice than basal or low-mix insulins. Similarly, Mix50 could be used during Ramadan to reduce PPG after the evening meal, which often contains a large caloric load [50]. Mix50 may also be an appropriate choice for patients at high risk of micro- and macrovascular complications caused by high glycemic variability [51]. Other factors, such as age, physical and mental capabilities, patient preferences, and lifestyle, should be considered when deciding between basal insulin and premixed insulins [7, 8], but apply equally to Mix50 and low-mix options. Many of these factors are less relevant for initial insulin therapy, but become important when the patient eventually requires intensification. Thus, clinicians should assess how the patient will cope best with additional injections and plan accordingly when deciding on initial treatment.

Dose and Regimen for Initiation with Mix50

Guidelines suggest initiating insulin (basal or premixed) at a dose of 10–12 units once daily before the largest meal (usually dinner) [1, 5, 6, 8]. The dose is then titrated once or twice weekly to achieve FBG levels of approximately 4–7 mmol/L without hypoglycemia. The same general approach can be used with Mix50, although titrating to a target PPG may also be considered. Another option is to split the dose across two injections, before breakfast and before dinner, which may suit patients who require more postprandial control after breakfast (e.g., those who eat a large carbohydrate-rich breakfast) or those at high risk of nocturnal hypoglycemia. In most cases, patients can continue with OHAs, especially metformin; however, discontinuing sulfonylureas should be considered because of the increased risk of hypoglycemia when used in combination with insulin. In addition to the standard information provided when initiating insulin, particular care should be taken to ensure that patients starting on Mix50 (or any prandial insulin) understand the risks and management of hypoglycemia.

Insulin Intensification with Mix50

Summary of Evidence

For patients requiring insulin intensification, the evidence suggests that Mix50 may provide better glycemic control compared with low-mix insulins, but not compared with basal–bolus regimens. Although two RCTs in this review concluded that Mix50, specifically BIAsp50, provided better glycemic control than low-mix insulins [15, 24], the other two RCTs reported no difference between the Lispro 50 and low mix [17, 25]. The reasons for these discrepancies are unclear, but may be related to differences in treatment regimen, treatment duration, or patient characteristics. However, as observed when used for initiation, Mix50 had a greater effect on PPG levels than low-mix insulins when used for intensification.

Compared with basal–bolus therapy, Mix50 is less efficacious at overall glycemic control, although again, there are inconsistencies between studies. However, there is evidence that Mix50 may have a greater effect on PPG levels than basal–bolus therapy, particularly the levels after breakfast and lunch [21, 27]. Issues of safety (i.e., hypoglycemia and weight gain) are generally similar between Mix50 and basal–bolus therapy.

Identifying Patients Suitable for Intensification with Mix50 (Fig. 3)

Several additional factors should be considered when determining whether Mix50 is suitable for individual patients who require intensification of their current insulin regimen. If the patient is already on a premixed insulin, consider switching from low mix to Mix50 and/or adding doses as part of a BID or TID regimen, especially at the meal(s) with the highest PPG excursions. If FPG target levels are not reached, consider changing the pre-dinner injection to a low-mix insulin and using Mix50 before breakfast (and lunch, if required). However, this option should be weighed against any patient preference for a simpler regimen with a single insulin injection device. Similarly, if the patient is currently on basal therapy, a regimen using Mix50 (or low mix) may be easier for the patient than a basal–bolus regimen, which requires multiple injection devices and frequent glucose monitoring. In contrast, patients with inconsistent timing or content of meals may benefit from the flexible dosing possible with a basal–bolus regimen. As with initiation, paired pre- and postprandial glucose concentrations, as well as the level of carbohydrate consumption, can be used to help decide which premixed insulin is most appropriate for an individual patient.

Dose and Regimen for Intensification with Mix50

When using premixed insulin for intensification, regardless of whether the initial dose is basal or premixed, standard practice is to divide the current total daily dose across two doses injected before breakfast and before dinner [1, 5, 6, 9]. Alternatively, Mix50 can be given before breakfast and a low mix before dinner to provide more overnight basal insulin. For patients currently on low mix, consider using Mix50 before any meal where PPG is > 10 mmol/L [9] or whichever meal routinely has the highest carbohydrate content. Dose titration follows the same general pattern as for patients on once-daily insulin [1, 5, 6, 8, 9]. However, the doses should be adjusted independently, depending on the glucose profile; adjust the pre-breakfast dose according to the pre-dinner glucose level and the pre-dinner dose according to the FBG level [6]. A third dose can be added before lunch if target HbA1c or PPG levels are not met. A general guideline for switching patients from low mix to Mix50 is shown in Fig. 4; however, as always, regimens and doses should be tailored to the individual patient.

Conclusion

We conducted a systematic literature review to assess the evidence for the use of Mix50 in patients with T2D. In conclusion, the collective evidence suggests that Mix50 is a suitable alternative for both initiation and intensification of insulin therapy that may be more appropriate than low-mix insulins for certain patients. Clinicians should consider not only efficacy and safety but also patient characteristics and preferences when tailoring insulin treatment to individuals with T2D.

References

American Diabetes Association. 8. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S64–74.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2016 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:84–113.

Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology—Clinical Practice Guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015—executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:413–37.

International Diabetes Federation Guideline Development Group. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104:1–52.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–9.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. General practice management of type 2 diabetes: 2016–2018. East Melbourne: RACGP; 2016.

Unnikrishnan AG, Tibaldi J, Hadley-Brown M, et al. Practical guidance on intensification of insulin therapy with BIAsp 30: a consensus statement. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1571–7.

Wu T, Betty B, Downie M, et al. Practical guidance on the use of premix insulin analogs in initiating, intensifying, or switching insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2015;6:273–87.

Brito M, Ligthelm RJ, Boemi M, et al. Intensifying existing premix therapy (BIAsp 30) with BIAsp 50 and BIAsp 70: a consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:152–60.

Tibaldi JM. Evolution of insulin: from human to analog. Am J Med. 2014;127:S25–38.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

Ilag LL, Kerr L, Malone JK, Tan MH. Prandial premixed insulin analogue regimens versus basal insulin analogue regimens in the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based comparison. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1254–70.

Qayyum R, Bolen S, Maruthur N, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and safety of premixed insulin analogues in type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:549–59.

Chen W, Qian L, Watada H, et al. Impact of diet on the efficacy of insulin lispro mix 25 and insulin lispro mix 50 as starter insulin in East Asian patients with type 2 diabetes: subgroup analysis of the comparison between low mixed insulin and mid mixed insulin as starter insulin for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (CLASSIFY study) randomized trial. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:75–83.

Cucinotta D, Smirnova O, Christiansen JS, et al. Three different premixed combinations of biphasic insulin aspart—comparison of the efficacy and safety in a randomized controlled clinical trial in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:700–8.

Domeki N, Matsumura M, Monden T, Nakatani Y, Aso Y. A randomized trial of step-up treatment with premixed insulin lispro-50/50 vs aspart-70/30 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5:403–13.

Farcasiu E, Ivanyi T, Mozejko-Pastewka B, et al. Efficacy and safety of prandial premixed therapy using insulin lispro mix 50/50 3 times daily compared with progressive titration of insulin lispro mix 75/25 or biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, 16-week, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1682–93.

Giugliano D, Tracz M, Shah S, et al. Initiation and gradual intensification of premixed insulin lispro therapy versus basal ± mealtime insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes eating light breakfasts. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:372–80.

Jacober SJ, Scism-Bacon JL, Zagar AJ, et al. A comparison of intensive mixture therapy with basal insulin therapy in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes receiving oral antidiabetes agents. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8:448–55.

Jain SM, Mao X, Escalante-Pulido M, Vorokhobina N, Lopez I, Ilag LL. Prandial-basal insulin regimens plus oral antihyperglycaemic agents to improve mealtime glycaemia: initiate and progressively advance insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:967–75.

Jia W, Xiao X, Ji Q, et al. Comparison of thrice-daily premixed insulin (insulin lispro premix) with basal–bolus (insulin glargine once-daily plus thrice-daily prandial insulin lispro) therapy in east Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled with twice-daily premixed insulin: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:162–254.

Kazda C, Hulstrunk H, Helsberg K, Langer F, Forst T, Hanefeld M. Prandial insulin substitution with insulin lispro or insulin lispro mid mixture vs. basal therapy with insulin glargine: a randomized controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes beginning insulin therapy. J Diabetes Complicat. 2006;20:145–52.

Miser WF, Arakaki R, Jiang H, Scism-Bacon J, Anderson PW, Fahrbach JL. Randomized, open-label, parallel-group evaluations of basal–bolus therapy versus insulin lispro premixed therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus failing to achieve control with starter insulin treatment and continuing oral antihyperglycemic drugs: a noninferiority intensification substudy of the DURABLE trial. Clin Ther. 2010;32:896–908.

Novo Nordisk. Effect of biphasic insulin aspart 50 compared to biphasic insulin aspart 30 both in combination with metformin in Chinese subjects with type 2 diabetes. http://www.novonordisk-trials.com/WebSite/search/TrialDetail.aspx?Command=GetTrialDetail&TrialId=BIASP-1858&Index=8. Accessed 13 Dec 2016.

Roach P, Arora V, Campaigne BN, Mattoo V, Rangwala S, India Mix25/Mix50 Study Group. Humalog Mix50 before carbohydrate-rich meals in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2003;5:311–6.

Robbins DC, Beisswenger PJ, Ceriello A, et al. Mealtime 50/50 basal + prandial insulin analogue mixture with a basal insulin analogue, both plus metformin, in the achievement of target HbA1c and pre- and postprandial blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a multinational, 24-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group comparison. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2349–64.

Rosenstock J, Ahmann AJ, Colon G, Scism-Bacon J, Jiang H, Martin S. Advancing insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes previously treated with glargine plus oral agents: prandial premixed (insulin lispro protamine suspension/lispro) versus basal/bolus (glargine/lispro) therapy. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:20–5.

Schwartz S, Zagar AJ, Althouse SK, Pinaire JA, Holcombe JH. A single-center, randomized, double-blind, three-way crossover study examining postchallenge glucose responses to human insulin 70/30 and insulin lispro fixed mixtures 75/25 and 50/50 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1649–57.

Su Q, Liu C, Zheng H, et al. Comparison of insulin lispro mix 25 with insulin lispro mix 50 as insulin starter in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (CLASSIFY study): subgroup analysis of a phase 4 open-label randomized trial. J Diabetes. 2017;9:575–85. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12442.

Suzuki K, Morikawa H, Iwanaga M, Aizawa Y. Investigation of the introduction of three times daily injections of Insulin Lispro Mixture-50 on an outpatient basis: therapeutic effects of 12 months’ treatment with and without concomitant sulfonylurea. J Diabetes. 2012;4:262–3.

Watada H, Su Q, Li PF, Iwamoto N, Qian L, Yang WY. Comparison of insulin lispro mix 25 with insulin lispro mix 50 as an insulin starter in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes: a phase 4, open-label, randomized trial (CLASSIFY study). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33:e2816.

Zafar MI, Ai X, Shafqat RA, Gao F. Effectiveness and safety of Humalog Mix 50/50 versus Humalog Mix 75/25 in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:27–32.

Davidson JA, Lacaya LB, Jiang H, et al. Impact of race/ethnicity on the efficacy and safety of commonly used insulin regimens: a post hoc analysis of clinical trials in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:818–28.

Hirsch IB, Yuan H, Campaigne BN, Tan MH. Impact of prandial plus basal vs basal insulin on glycemic variability in type 2 diabetic patients. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:343–8.

Akahori H. Clinical evaluation of thrice-daily lispro 50/50 versus twice-daily aspart 70/30 on blood glucose fluctuation and postprandial hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Int. 2015;6:275–83.

Ito H, Abe M, Antoku S, et al. Effects of switching from prandial premixed insulin therapy to basal plus two times bolus insulin therapy on glycemic control and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:391–6.

Mashitani T, Tsujii S, Hayashino Y, et al. Diurnal patterns of plasma glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving sulfonylurea and effectiveness of once daily lispro mix 50/50 injections. Diabetol Int. 2014;5:30–5.

Nakashima E, Kuribayashi N, Ishida K, Taketsuna M, Takeuchi M, Imaoka T. Efficacy and safety of stepwise introduction of insulin lispro mix 50 in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by oral therapy. Endocr J. 2013;60:763–72.

Novo Nordisk. Observational study of NovoMix® 50 for treatment of type 2 diabetics for 12 months. http://www.novonordisk-trials.com/WebSite/search/TrialDetail.aspx?Command=GetTrialDetail&TrialId=BIASP-3674&Index=0. Accessed 13 Dec 2016.

Novo Nordisk. Observational study on safety and efficacy of biphasic insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes patients. http://www.novonordisk-trials.com/WebSite/search/TrialDetail.aspx?Command=GetTrialDetail&TrialId=BIASP-3669&Index=0 Accessed 13 Dec 2016.

Shimizu H, Monden T, Matsumura M, Domeki N, Kasai K. Effects of twice-daily injections of premixed insulin analog on glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:845–9.

Tanaka M, Ishii H. Pre-mixed rapid-acting insulin 50/50 analogue twice daily is useful not only for controlling post-prandial blood glucose, but also for stabilizing the diurnal variation of blood glucose levels: switching from pre-mixed insulin 70/30 or 75/25 to pre-mixed insulin 50/50. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:674–80.

Tanaka M, Ishii H. Improvement in bedtime plasma glucose level serves as a predictor of long-term blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a study with monotherapy of 50/50 premixed insulin analogue three times daily injection. J Diabetes Complicat. 2011;25:83–9.

Yamashiro K, Ikeda F, Fujitani Y, Watada H, Kawamori R, Hirose T. Comparison of thrice-daily lispro 50/50 vs thrice-daily lispro in combination with sulfonylurea as initial insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2010;1:149–53.

Cho KY, Nakagaki O, Miyoshi H, Akikawa K, Astumi T. Evaluation of thrice-daily injections of insulin Lispro Mix 50/50 versus basal–bolus therapy in perioperative patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Int. 2014;5:117–21.

Buse JB, Wolffenbuttel BH, Herman WH, et al. DURAbility of basal versus lispro mix 75/25 insulin efficacy (DURABLE) trial 24-week results: safety and efficacy of insulin lispro mix 75/25 versus insulin glargine added to oral antihyperglycemic drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1007–13.

Goh S-Y, Hussein Z, Rudijanto A. Review of insulin-associated hypoglycemia and its impact on the management of diabetes in Southeast Asian countries. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8:635–45. doi:10.1111/jdi.12647.

Kataoka M, Venn BJ, Williams SM, Te Morenga LA, Heemels IM, Mann JI. Glycaemic responses to glucose and rice in people of Chinese and European ethnicity. Diabet Med. 2013;30:e101–7.

Møller JB, Dalla Man C, Overgaard RV, et al. Ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity, β-cell function, and hepatic extraction between Japanese and Caucasians: a minimal model analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:4273–80.

Pathan MF, Sahay RK, Zargar AH, et al. South Asian Consensus Guideline: use of insulin in diabetes during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:499–502.

Gorst C, Kwok CS, Aslam S, et al. Long-term glycemic variability and risk of adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2354–69.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, manufacturer/licensee of Humalog. Eli Lilly funded the article processing charges. Medical writing assistance was provided by Rebecca Lew, PhD, CMPP and Janelle Keys, PhD, CMPP of ProScribe—Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for good publication practice (GPP3). Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this manuscript and have given final approval for this version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors participated in the interpretation of the systematic review findings and the clinical perspective and recommendations, as well as the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. GD, GK, and TW were also involved in the literature search design. The authors would like to thank Helen Barraclough and Bradley Curtis, employees of Eli Lilly and Company, for helpful discussions during the initiation of this review.

Disclosures

Richard Cutfield has served as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. Gary Deed has served as a consultant, speaker, and/or advisory board member for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda. Trisha Dunning has served as a consultant, advisory board member, and/or on a board of directors for The International Diabetes Federation and Diabetes Victoria and received speaker honoraria from Sanofi Aventis. Gary Kilov has served as a consultant, speaker, and/or advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Sanofi, and Servier. Jane Overland has served as a speaker for and/or received research funding from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk, and Roche. Ted Wu has served as a consultant, speaker, and/or advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/3CCCF0604D514F92.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Deed, G., Kilov, G., Dunning, T. et al. Use of 50/50 Premixed Insulin Analogs in Type 2 Diabetes: Systematic Review and Clinical Recommendations. Diabetes Ther 8, 1265–1296 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0328-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0328-6