Abstract

Purpose

Pesticides are applied to agricultural fields to optimise crop yield and their global use is substantial. Their consideration in life cycle assessment (LCA) is affected by important inconsistencies between the emission inventory and impact assessment phases of LCA. A clear definition of the delineation between the product system model (life cycle inventory—LCI, technosphere) and the natural environment (life cycle impact assessment—LCIA, ecosphere) is missing and could be established via consensus building.

Methods

A workshop held in 2013 in Glasgow, UK, had the goal of establishing consensus and creating clear guidelines in the following topics: (1) boundary between emission inventory and impact characterisation model, (2) spatial dimensions and the time periods assumed for the application of substances to open agricultural fields or in greenhouses and (3) emissions to the natural environment and their potential impacts. More than 30 specialists in agrifood LCI, LCIA, risk assessment and ecotoxicology, representing industry, government and academia from 15 countries and four continents, met to discuss and reach consensus. The resulting guidelines target LCA practitioners, data (base) and characterisation method developers, and decision makers.

Results and discussion

The focus was on defining a clear interface between LCI and LCIA, capable of supporting any goal and scope requirements while avoiding double counting or exclusion of important emission flows/impacts. Consensus was reached accordingly on distinct sets of recommendations for LCI and LCIA, respectively, recommending, for example, that buffer zones should be considered as part of the crop production system and the change in yield be considered. While the spatial dimensions of the field were not fixed, the temporal boundary between dynamic LCI fate modelling and steady-state LCIA fate modelling needs to be defined.

Conclusions and recommendations

For pesticide application, the inventory should report pesticide identification, crop, mass applied per active ingredient, application method or formulation type, presence of buffer zones, location/country, application time before harvest and crop growth stage during application, adherence with Good Agricultural Practice, and whether the field is considered part of the technosphere or the ecosphere. Additionally, emission fractions to environmental media on-field and off-field should be reported. For LCIA, the directly concerned impact categories and a list of relevant fate and exposure processes were identified. Next steps were identified: (1) establishing default emission fractions to environmental media for integration into LCI databases and (2) interaction among impact model developers to extend current methods with new elements/processes mentioned in the recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

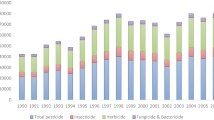

Pesticides, such as fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides, plant growth regulators, and defoliants are applied to agricultural fields in order to optimise crop yield. Agricultural pesticide use is substantial and amounts globally to about 1.2 million metric tons of active ingredients (the biologically active part of a commercial pesticide formulation) per year between 2005 and 2010 (FAO 2013). In contrast to regulatory assessments, life cycle assessment (LCA) is not used to analyse (or question) product risk or safety, but instead supports to establish and inform environmental performance profiles aiming to identify the most environmentally sustainable way(s) of providing a product or service between different options. These may, for example, range from various functionally equivalent pesticides applied in conventional agriculture to alternative solutions, such as organic or integrated farming practices. Whatever the choice of alternatives, LCA should be able to reliably identify the trade-offs between alternative solutions.

In practice, this ideal is currently hampered by significant inconsistencies between emission inventory modelling and impact assessment, two distinct phases of an LCA study. Notably, a clear definition of the delineation between the product system model as represented in the life cycle inventory (LCI) (i.e. technosphere) and the natural environment as represented by life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) characterisation models (i.e. ecosphere) is currently missing (Dijkman et al. 2012). The typical difficulty with respect to pesticides is to quantify the proportion emitted to the different media in the ecosphere, while usually only the amount applied to the agricultural field is known. This leads to the core question of considering the field as part of the ecosphere or technosphere, which is also related to different agricultural practices (e.g. organic vs. conventional) and represents a modelling choice that is currently inconsistently handled in LCA practice (Hellweg and Geisler 2003; Birkved and Hauschild 2006; Nemecek and Kägi 2007; Dijkman et al. 2012; van Zelm et al. 2014). As a consequence, several approaches and hypotheses have been proposed and used up to now, which leads to inconsistent results and may not always represent realistic conditions.

In 2003, the (Swiss) Discussion Forum on LCA approached the subject of pesticide emission and impact modelling in LCA, providing an overview of LCIA models for pesticides and showing directions for further development (Hellweg and Geisler 2003). Although more than 10 years have passed since then, several of their conclusions remain valid, stating, e.g. that: (1) “the correlation between spatial variability on the one hand and regionally different crops and agricultural management practices on the other hand is not taken into account in LCA.”Footnote 1; and (2) underlying assumptions and the model performances [of LCIA methods] need further validation and verification”, p. 312 in Hellweg and Geisler (2003).

A wealth of information is available in the literature on fate and transport processes of pesticides after application to agricultural fields, such as spray drift including deposition, volatilisation, leaching, runoff, washoff and plant uptake, as well as influencing factors such as buffer zones, application method, temperature, crop/soil type, and degradation, or special cases such as greenhouses. An overview (non-exhaustive) is given in Table 1.

These processes and conditions mainly influence how much of a pesticide applied to a field will be transported from the field into different environmental media, which is a first step in the environmental fate modelling of these chemicals. These processes depend on a number of factors and in particular on the active ingredient, the formulation containing it, the application method, weather conditions (before, during, and after application), soil conditions, crop characteristics, and whether and how irrigation is used. This complexity creates a substantial obstacle to a consistent quantification of agricultural emissions to environmental media.

In LCA, environmental fate of a chemical emission to the ecosphere is usually modelled in a generic way during the impact assessment phase. However, given the important influence of local conditions and agricultural practice on the first step of the environmental fate of pesticides (i.e. from field application to transport to off-field air, water and natural soil), using generic fate factors leads to extremely high uncertainty. For this reason, the field may be considered as being part of the technosphere and the first step of fate modelling is thus considered as part of the inventory modelling. Although, inconsistencies exist between this first step of site-specific and agricultural practice-specific fate modelling included in the inventory phase and the next steps of generic fate, exposure and effect modelling of toxic substances included in the impact assessment phase.

With the goal of establishing consensus, a full-day expert workshop was organised in a collaborative effort between the Division for Quantitative Sustainability Assessment of the Technical University of Denmark and Quantis on Saturday 11 May 2013 in Glasgow, UK, back to back with the 23rd SETAC Europe meeting. More than 30 specialists, representing industry, government and academia from 15 countries and four continents, participated (see Electronic Supplementary Material).

The objective of the workshop was to create consensus and clear guidelines for LCA practitioners, data (base) and characterisation method developers, and decision makers where the boundary between the product system model representing the technosphere (emission inventory) and the environmental characterisation model representing the ecosphere (impact assessment) should be set in all three spatial dimensions and time when considering the application of substances to an open agricultural field or in greenhouses, and consequent emissions to the natural environment and their potential impacts. The workshop explicitly excluded discussions on how to quantify emissions or related impacts of pesticides, while focusing on clearly defining what should be quantified in the emission inventory of the product system and what should be quantified by the characterisation factors (CF) from the impact characterisation models, avoiding any overlap or double counting of chemical fate processes to be considered. In setting guidelines and recommendations, the workgroup focused on issues of science and scientific consensus and avoided recommendations that would be dependent on or endorse a specific model.

2 Methods

2.1 Life cycle inventory

In order to at least provide meaningful emission estimates, LCA practitioners and developers proposed generic assumptions regarding varying percentages of applied active ingredient emitted to environmental media (Margni et al. 2002; Audsley et al. 2003; Panichelli et al. 2008) and in greenhouses (Antón et al. 2004; Juraske et al. 2007). Furthermore, a number of very different (i.e. inconsistent) approaches and assumptions are currently applied in quantifying life cycle emission inventories of pesticides in any LCA study involving agricultural systems, for example:

-

1)

The widely used life cycle inventory database Ecoinvent adopted the assumption that the amount of pesticide applied is emitted 100 % to agricultural soil (Nemecek and Kägi 2007).

-

2)

In the US Life Cycle Inventory Database (NREL 2012), pesticide emissions are inventoried as emissions to air and water based primarily on leaching and runoff data from US EPA (1999) and Kellogg et al. (2002).

-

3)

The pesticide emission model PestLCI 2.0 (Dijkman et al. 2012) employs a local fate model that estimates the amounts emitted (meaning here leaving the agricultural field) to air, surface water, and ground water through the soil, respectively, based on application methods, local meteorological conditions, crop types, and other influencing factors. This model considers the agricultural soil as part of the technosphere.

-

4)

The recent US field crop LCI database “USDA LCA Digital Commons” does not consider any fate and transport losses and clearly reports release of pesticides to agricultural soil, and also to air when relevant according to the application method inventoried (Cooper et al. 2013; http://www.lcacommons.gov).

Choosing among these available approaches will have an important influence on the results of the LCI as illustrated in Table 2 for a simplified example like the application of 2,4-D to corn.

2.2 Life cycle impact assessment

All current LCIA characterisation models for toxicity, such as IMPACT 2002 (Pennington et al. 2005)—used in IMPACT 2002+ (Jolliet et al. 2003), USES-LCA (van Zelm et al. 2009)—applied in ReCiPe (Goedkoop et al. 2012), and USEtox (Rosenbaum et al. 2008)—adopted by ILCD (EC-JRC 2011) and TRACI 2.0 (Bare 2011), consider the fate (transport, distribution and degradation) of a pesticide, once emitted to the ecosphere (= natural environment), i.e. air, water, and soil outside the agricultural field. Nevertheless, both USEtox and USES-LCA differentiate between agricultural and natural soil as environmental media. The USEtox developers included agricultural soil arguing that “using two soil types, agricultural and natural soil, accounts for the fraction of agricultural soil relative to the total soil surface and also allows for specific (e.g. pesticide) emissions occurring on agricultural soil only” (Rosenbaum et al. 2008). For ecotoxicity, USEtox only accounts for freshwater ecotoxicity and does currently not provide factors for terrestrial ecotoxicity impacts on (or off) the agricultural field due to missing data and appropriate models that could provide a solid basis for a consensus. Therefore, only impacts outside the agricultural field and its soil (i.e. only effects occurring in the ecosphere) are characterised.

In practice, this means that the practitioner has two options at the moment: (1) a pesticide emission model (like PestLCI 2.0) used in combination with characterization factors (CFs) for emissions to off-field environmental media (e.g. natural soil, air, freshwater in the case of USEtox) or (2) the amount applied to the agricultural field is used and characterised with a CF for on-field emissions (e.g. to agricultural soil in USEtox—CFs for all other emission media are representing off-field emission media and are thus not applicable). In the absence of widely applicable pesticide emission models at the time, this was considered an approximate solution for pesticide emissions, but many important factors and fate processes such as wind drift, application method, buffer zones, plant deposit, etc. are not modelled and a CF for an emission to agricultural soil in USEtox comes with considerable model uncertainty of at least two to three orders of magnitude (excluding uncertainty due to missing transport processes) (Rosenbaum et al. 2008).

With the inherent assumption of steady-state conditions, the dynamic fate processes taking place between the application and the moment the substance is transported outside the agricultural field are not explicitly modelled in LCIA and are hence presently expected to be represented by LCI data. An implicit assumption thereby is that the field is part of the technosphere, which means that impacts to the environment/ecosystem on the field are not specifically considered. In consequence, all currently used toxicity LCIA models are incompatible with LCI data representing the amount applied to the field. This is true for ecosystem as well as human health LCIA models, although some exceptions to this general rule exist for specific impact pathway mechanisms, for example, the human health characterisation model for pesticide residues in food crops by Fantke et al. (2011b), which requires information on the quantity applied to the field, rather than the consequent environmental emissions.

2.3 Workshop resume

In order to preserve consistency with the characterisation of other chemical emissions, there seems to be limited flexibility to adapt LCIA characterisation modelling; hence, the most practical way to improve the consideration of pesticide field applications in LCA may be to focus on clearly defining the inventory requirements for pesticide emissions as illustrated in Fig. 1. Many definitions of delineations between LCI and LCIA are possible that respect the requirements that all flows between environmental media connect and the mass balance is conserved, but it is essential that all stakeholders (i.e. LCI/LCIA modellers and LCA practitioners) are using a consistent approach. Therefore, a consensus-based definition of a convention and related guidance for LCA practitioners and methodology developers is required and was the main objective of the Glasgow pesticide workshop.

Conceptual representation of emissions to various environmental media occurring after application of a pesticide to a crop on an agricultural field (based on Birkved and Hauschild (2006))

While a brief overview will be given hereafter, the complete minutes, details, and most slides presented during the workshop can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material. The workshop started with four presentations providing experiences and perspectives of LCA practitioners, emission inventory practice and impact assessment developers.

Presenting a practitioner’s perspective, Sebastien Humbert (Quantis) pointed out that “Between 1 to 5 h (max) can be allocated by practitioners to modelling inventory of pesticides for one crop. Therefore, practical and efficient solutions are needed.” Current issues encountered when conducting an LCA are (a) media of substance application and related fraction emitted to each medium to be considered, (b) missing guidelines for greenhouses (Are they part of the technosphere or the ecosphere?), (c) other issues related to formulation additives and pesticide degradation products, (d) potential double counting with land occupation (in some LCIA methods, characterisation factors for land occupation may already account for reduced biodiversity due to pesticides used), (e) consideration of water quality in water footprinting (classically, for water pollution caused by pesticides only the fraction directly going to water is considered in water footprints, but if a pesticide is emitted to soil and air, a fraction of these emissions will also end up in water via e.g. deposition, runoff, or leaching. How should this be accounted for?) and (f) default values should be applied to generic conditions and the selected model should be flexible to adapt values representing local conditions.

Teunis Dijkman (DTU) presented and compared three examples of current practice in LCI modelling (Ecoinvent, US LCI, and PestLCI 2.0, see Table 2), with a focus on the delineation between technosphere and ecosphere and transport processes considered in PestLCI 2.0. He concluded that (a) different LCI approaches and system boundary choices lead to incomparable LCA studies where toxicity results can differ by orders of magnitude, depending on the emission model chosen, (b) modelling fate processes in LCI does not lead to double counting of fate processes and (c) clearly defining a technosphere-ecosphere boundary is essential.

Peter Fantke (DTU) provided an overview of current LCIA modelling practice. Among others, he pointed out a number of potentially relevant agricultural chemical emissions which are not yet covered by LCIA methods. Examples are pesticide formulation by-products (adjuvants, solvents, etc.), phytohormones used as plant growth regulators, animal manure by-products (livestock antibiotics and hormones), sewage sludge constituents (metals, bacteria, etc.) and degradation products (metabolites). “None of these are covered in current LCIA practice, but can we nevertheless assume the same conditions regarding system boundaries?” He identified open questions regarding consistent system boundaries for LCIA: (a) How to address species migrating between technosphere and ecosphere? (b) How to address species living from the technosphere (e.g. birds feeding on insects living in agricultural fields)? (c) How to consider applied mass for impacts from crop intake? He also named a number of LCIA important principles for pesticides: (a) include predominant human exposure pathways: intake of treated crops, (b) consider time dimensions for exposure via crop intake and (c) allow comparison with exposed population subgroups (e.g. bystanders, operators, etc.).

Rosalie van Zelm (Radboud University) presented work done in collaboration with Irstea (France) focusing on the boundary of LCI and LCIA so as to frame what modelling should be included in LCI and what in LCIA in order to prevent gaps and overlaps (van Zelm et al. 2014). She outlined the issues that we further and more thoroughly discussed in the meeting. Finally, a case study on bananas was presented applying the proposed framework. It showed the importance of a good integration of LCI-LCIA methodology allowing to quantify differences between efficient vs. inefficient agricultural practices taking into account pre- and post-treatment pesticide flows (e.g. cleaning of equipment), use of buffer zones, and (over)dosing. This work was recently published (van Zelm et al. 2014), proposing a framework to bridge the gap and prevent overlaps between LCI and LCIA for toxicological assessments of pesticides.

With these inputs, the discussion was launched with a number of issues and open questions identified beforehand as starting points for the discussion:

-

Is the ecosystem on the agricultural field (e.g. aerial such as insects and pollinators, terrestrial and deep soil ecosystems) part of the area of protection (natural environment) and should thus be addressed in the impact assessment or is it a highly controlled ecosystem anyway and essentially part of the technosphere and then (at least partially) covered in the land use impact category (which inherently includes changes in biodiversity due to pesticide application as part of some land-use types)?

-

Does it lead to double counting if both the inventory model and the impact model involve a fate modelling step or can these be distinguished clearly and consistently across substances and conditions?

-

Spatial dimensions: If the field is considered as part of the technosphere, can we define the agricultural field as a 3-dimensional box by height of air above the field, width and length of the field including buffer zones, and soil depth? Then only the fraction(s) of an applied pesticide leaving this box to various environmental media would be accounted for in the emission inventory.

-

Temporal dimensions: Pesticides are typically applied in pulses. Does the assumption of similarity between pulse and continuous emissions in the steady-state model of LCA also hold for such emission dynamics? How can it be determined, when steady-state assumptions are satisfactory and when not? Which periods of time from application to ecosphere emissions need to be taken into account in the emission inventory and in the impact assessment?

-

Mass applied vs. mass emitted – what information does the emission inventory need to provide? Which emission media are relevant to cover: air, surface water, ground water, deeper soil layer(s), others? Intake of pesticide residues in food products may be the dominating human exposure pathway in most cases, but requires the inventory to also report the quantity applied directly to the crop and not just the emission to the environmental media. Therefore, a clear definition of what needs to be reported and how in the life cycle inventory is needed.

-

Which impact pathways (e.g. direct and indirect human exposure via food residues, inhalation, drinking water, or terrestrial/aquatic/aerial ecosystems on-/off-field, etc.) and indicators (human toxicity, ecotoxicity, species richness, functional diversity, etc.) should be covered for pesticides?

-

Are different recommendations required for specific cases such as greenhouses, irrigated vs. non-irrigated fields, etc.?

The discussions during the workshop were comprehensive, focused and very productive, resulting in the recommendations presented in the following section.

3 Results and discussion

A balanced assessment of toxicity effects due to pesticide emissions (i.e. to environmental media, which is not the same as the amount of pesticide used/applied) associated to their agricultural use in the context of LCA is strongly desirable, allowing for the consideration of both advantages and disadvantages of using pesticides or choosing an alternative approach instead. Recommended practice should enable the assessment of trade-offs between potential negative biodiversity impacts pesticides may cause on and around the field and positive indirect effects on biodiversity due to increased yield and thus less land-use compared to avoiding pesticide application.

In Table 3, the main results from the discussion around the essential core questions of allocation of the agricultural field to technosphere or ecosphere, as well as its spatial and temporal dimensions, are presented. These questions were the starting point of the discussion during the workshop, and the initial goal was to arrive at recommendations to answer the questions. However, it became clear that there is a strong dependency on goal and scope of an LCA study and that fixing these would not allow certain assessment goals. Instead, the focus was on defining a clear interface between LCI and LCIA. This should be capable of supporting any goal and scope requirements while avoiding double counting or excluding important emission flows (and their potential impacts). The detailed recommendations are given in section 4.

4 Conclusions and recommendations

The boundary between technosphere/ecosphere and allocation of the agricultural field to either technosphere or ecosphere and its spatial dimension was and should not be fixed on a general level but depend on the goal and scope of the LCA study. Instead, we recommend a number of emission flows, both on and off the field, that need to be quantified in the LCI in order to characterise specific impacts, which may take place on or off the field.

Consensus was reached on distinct sets of recommendations for LCI and LCIA, respectively, which are presented hereafter. This establishes a clearly defined interface between LCI and LCIA.

Life cycle inventory recommendations:

-

1.

For pesticides application, the LCI should report the following information (per functional unit):

-

(a)

Pesticide identification (CAS registry numbers and names of active ingredients per applied plant protection product, PPP).

-

(b)

Crop.

-

(c)

Mass applied of each active ingredient.

-

(d)

Application method (foliar spray, soil injection, drip irrigation) or formulation type (soluble concentrate, granule, wettable powder).

-

(e)

Presence of buffer zones (y/n).

-

(f)

Location/country (which identifies a default local scenario/site incl. climate, soil conditions, present environmental media, …).

-

(g)

Application time in days before harvest (for human health impacts) and crop growth stage (for terrestrial/aerial ecosystem impacts) during application.

-

(h)

Adherence with Good Agricultural Practice(s)—GAP, such as discussed and defined by FAO (2003) (with adjustable parameters including pre- and post-treatment pesticide flows, e.g. equipment cleaning, tanks and cans residues, etc.), in order to be able to distinguish different levels of agricultural practice from good (i.e. efficient) to average to inefficient (e.g. overdosing, application during precipitation events, etc.).

-

(i)

The goal and scope section of an LCA should clearly state whether the agricultural field is assumed as part of the technosphere or the ecosphere.

-

(a)

-

2.

We recommend the explicit reporting of emission fractions, i.e. fractions of the applied pesticide emitted to environmental media via initial distribution from the applied mass based on models and/or measurements with mass fractions going directly to:

-

(a)

On-field:

-

Soil surface (excluding plant deposit)

-

Paddy water (excluding plant deposit), e.g. for paddy rice

-

Plant (plant deposit)

-

-

(b)

Off-field:

-

Air (via volatilization on-field and wind drift, fraction not deposited close to the field)

-

Surface water (via spray drift deposition, excluding runoff, avoiding double counting with air (of which a fraction eventually redeposits on surface water at long distance); distinguishing fresh and marine water as far as possible and meaningful

-

Soil (distinguishing types [natural, industrial, agricultural, etc.] if possible)

-

-

(a)

-

3.

The emission fractions to environmental media via initial distribution and the degraded fraction should always sum up to 100 % of the quantity applied to the field in order to maintain conservation of mass and to allow for assessment of all potential impacts in the LCIA.

-

4.

There should be archetypical/default sets of values for these emission fractions to environmental media via initial distribution depending on conditions of applications that could be replaced if measured or more detailed information is available. These will be quantified and agreed upon in a follow-up workshop in Basel in May 2014.

-

5.

As a starting point, default values may correspond to current average agricultural practice that may be spatially differentiated.

-

6.

Good practice in greenhouses should lead to minimum emissions, but fractions on greenhouse soil surface (excluding plant deposit), plant, leaching through the top soil layer and emissions to air outside the greenhouse should be quantified.

-

7.

In case buffer zones are present, they should be considered as part of the crop (production system) and the change in yield per hectare and the emission fractions to environmental media via initial distribution to off-field soil/surface water accounted for accordingly. Therefore, no specific CFs are required for buffer zones as these will be treated the same way as the rest of the agricultural field.

-

(a)

Runoff, accounted for in the impact assessment, would have to be modelled accordingly.

-

(a)

-

8.

Care should be taken to avoid double counting between the multimedia transfers of these emission fractions and the impact assessment fate model, thus the decision to only have the emission to environmental media via initial distribution in the inventory and subsequent transfers considered in the impact assessment. This is supported by furthermore distinguishing between initial distribution processes in LCI, where steady-state conditions are typically not (yet) reached and a dynamic assessment is required (Rein et al. 2011; Fantke et al. 2013), and fate processes in LCIA, for which steady state is typically assumed based on continuous diffusive, advective, and degradation processes.

Life cycle impact assessment recommendations:

-

1.

Relevant impact categories (with temporal aspects built in):

-

(a)

Land-use biodiversity impact on-field

-

(b)

Toxicity biodiversity impact off-field (terrestrial, aerial, freshwater, groundwater)

-

(c)

Toxicity human health off-field (including residues in treated crops for subsequent human exposure via crop consumption as a potentially predominant exposure pathway, bystander)

-

(d)

Toxicity human health on-field, e.g. occupational exposure, should be further explored

-

(a)

-

2.

LCIA methods should allow for the flexibility to define the agricultural field as part of the technosphere or the ecosphere in the goal and scope of a study (see Table 3), and CFs should be clearly labelled or documented as representing potential impacts in the ecosphere or the technosphere (e.g. terrestrial ecotoxicity on agricultural soil) if a specific assumption is required.

-

3.

Impact assessment should model:

-

(a)

Fate:

-

Secondary drainage

-

Runoff

-

Degradation

-

Volatilization

-

Transfer (leaching) to groundwater and deeper soil layers on the field

-

Residues in entire crop of which some parts might remain on the field after harvest, leading to possible subsequent runoff/leaching and resulting background concentrations, or to exposure via fodder for animals or compost (with pesticide residues)

-

-

(b)

Human exposure, eventually including bystanders, applicators, field workers, etc.

-

(a)

-

4.

The plant fraction that is washed off is not yet considered in impact assessment, and only the fraction effectively transferred from root to soil could be added to the primary soil emission until properly modelled. Whether washoff can/should be included or not is a function of the scenario, i.e. at good or average agricultural practice, washoff is negligible, and for application shortly before rain events, washoff may become relevant or even dominant.

-

5.

Compatibility between the dynamic fate modelling for the initial emission fractions and the subsequent steady-state fate modelling in LCIA needs to be acquired to avoid double counting or omissions of mass transport processes. This notably involves the consideration of the temporary boundary applied to the dynamic emission model.

-

6.

Impact assessment methods should also report which multimedia transfers are considered and recommend how the environmental medium may be linked to the mass applied.

-

7.

Open issues:

-

(a)

What is the influence of irrigation and how should it be modelled?

-

(b)

Care should be taken to avoid potential double counting between terrestrial ecotoxicity on agricultural soil and land use impacts on biodiversity due to agricultural soil use. Therefore, the characterisation models for these impact categories need to be harmonised (i.e. a decision is required on how and in which impact category these are modelled) when developing impact assessment methods for these impact categories.

-

(a)

-

8.

Further observation raised during the meeting:

-

(a)

Ecotoxicological impacts linked to background concentrations from earlier applications (e.g. with persistent substances) after crop harvest as function of crop rotation practice need to be accounted for.

-

(b)

For direct impact on the on-field soil, only the additional impact on ecosystem due to the PPP application (above the already considered effect of agricultural land use) should be considered when we are comparing different scenarios.

-

(a)

Next steps and future work discussed and identified during the workshop focused on the operationalisation of the recommendations in order to integrate them into LCA practice. Identified actions were:

-

Establishment of recommended default emission fractions to environmental media via initial distribution including the definition of the underlying temporal dimension of the dynamic LCI modelling. The results should be integrated into LCI databases. This is the goal of a follow-up workshop on 10 May 2014 in Basel.

-

Organisation of interaction with LCI database developers in order to help implement the recommendations.

-

Interaction among LCIA developers to extend current methods with new elements/processes mentioned in the recommendations, including targeted technical workshops on “how to” model specific processes.

-

Launching of a similar initiative to establish consensus about fertiliser emissions and impact assessment.

Notes

Our interpretation of this phrase is that it refers to the spatial variability of a number of (partially) correlated factors including local environmental conditions, crops produced and agricultural management practices applied.

References

Akbar TA, Lin H (2010) GIS based ArcPRZM-3 model for bentazon leaching towards groundwater. J Environ Sci (China) 22:1854–1859

Antón A, Castells F, Montero JI, Huijbregts M (2004) Comparison of toxicological impacts of integrated and chemical pest management in Mediterranean greenhouses. Chemosphere 54:1225–1235

Armstrong AC, Matthews AM, Portwood AM, Leeds-Harrison PB, Jarvis NJ (2000) CRACK-NP: a pesticide leaching model for cracking clay soils. Agric Water Manag 44:85–104

Audsley E, Alber S, Clift R, Cowell S, Crettaz P, Gaillard G, Hausheer J, Jolliet O, Kleijn R, Mortensen B, Pearce D, Roger E, Teulon H, Weidema B, Van Zeijts H (2003) Harmonisation of environmental life cycle assessment for agriculture. Eur Comm DG VI Agric 101

Bare J (2011) TRACI 2.0: the tool for the reduction and assessment of chemical and other environmental impacts 2.0. Clean Technol Environ Policy 13:687–696

Bedos C, Cellier P, Calvet R, Barriuso E, Gabrielle B (2002a) Mass transfer of pesticides into the atmosphere by volatilization from soils and plants: overview. Agronomie 22:21–33

Bedos C, Rousseau-Djabri M-F, Flura D, Masson S, Barriuso E, Cellier P (2002b) Rate of pesticide volatilization from soil: an experimental approach with a wind tunnel system applied to trifluralin. Atmos Environ 36:5917–5925

Bedos C, Génermont S, Le Cadre E, Garcia L, Barriuso E, Cellier P (2009) Modelling pesticide volatilization after soil application using the mechanistic model Volt’Air. Atmos Environ 43:3630–3639

Berenzen N, Lentzen-Godding A, Probst M, Schulz H, Schulz R, Liess M (2005) A comparison of predicted and measured levels of runoff-related pesticide concentrations in small lowland streams on a landscape level. Chemosphere 58:683–691

Bilanin AJ, Teske ME, Barry JW, Ekblad RB (1989) AGDISP: the aircraft spray dispersion model, code development and experimental validation. Trans ASABE 32:327–334

Bird SL, Perry SG, Ray SL, Teske ME (2002) Evaluation of the AgDISP aerial spray algorithms in the AgDRIFT model. Environ Toxicol Chem 21:672–681

Birkved M, Hauschild MZ (2006) PestLCI—a model for estimating field emissions of pesticides in agricultural LCA. Ecol Model 198:433–451

Boesten JJTI, Aden K, Beigel C, Beulke S, Dust M, Dyson JS, Fomsgaard IS, Jones RL, Karlsson S, van der Linden AMA, Richter O, Magrans JO, Soulas G (2006) Guidance document on estimating persistence and degradation kinetics from environmental fate studies on pesticides in EU registration. 434

Butler-Ellis MC, Lane AG, O’Sullivan CM, Miller PCH, Glass CR (2010) Bystander exposure to pesticide spray drift: new data for model development and validation. Biosyst Eng 107:162–168

Cohen ML, Steinmetz WD (1986) Foliar washoff of pesticides by rainfall. Environ Sci Technol 20:521–523

Collins C, Martin I, Doucette W (2011) Plant Uptake of Xenobiotics. In: Schröder P, Collins CD (eds) Org. Xenobiotics Plants SE - 1. Springer Netherlands, pp 3–16

Cooper J, Kahn E, Ebel R (2013) Sampling error in US field crop unit process data for life cycle assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 18:185–192

Davie-Martin CL, Hageman KJ, Chin Y-P (2013a) An improved screening tool for predicting volatilization of pesticides applied to soils. Environ Sci Technol 47:868–876

Davie-Martin CL, Hageman KJ, Chin Y-P (2013b) Correction to an improved screening tool for predicting volatilization of pesticides applied to soils. Environ Sci Technol 47:4956–4957

De Snoo GR, De Wit PJ (1998) Buffer zones for reducing pesticide drift to ditches and risks to aquatic organisms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 41:112–118

Dijkman TJ, Birkved M, Hauschild MZ (2012) PestLCI 2.0: a second generation model for estimating emissions of pesticides from arable land in LCA. Int J Life Cycle Assess 17:973–986

EC-JRC (2011) International reference life cycle data system (ILCD) handbook—recommendations for life cycle impact assessment in the European context, First edit. European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment and Sustainability, Ispra, Italy

Fantke P, Juraske R (2013) Variability of pesticide dissipation half-lives in plants. Environ Sci Technol 47:3548–3562

Fantke P, Charles R, De Alencastro LF, Friedrich R, Jolliet O (2011a) Plant uptake of pesticides and human health: dynamic modeling of residues in wheat and ingestion intake. Chemosphere 85:1639–1647

Fantke P, Juraske R, Antón A, Friedrich R, Jolliet O (2011b) Dynamic multicrop model to characterize impacts of pesticides in food. Environ Sci Technol 45:8842–8849

Fantke P, Wieland P, Wannaz C, Friedrich R, Jolliet O (2013) Dynamics of pesticide uptake into plants: from system functioning to parsimonious modeling. Environ Model Softw 40:316–324

Fantke P, Gillespie BW, Juraske R, Jolliet O (2014) Estimating half-lives for pesticide dissipation from plants. Environ Sci Technol 48:8588–8602

FAO (2003) Development of a framework for good agricultural practices. Rome, Italy

FAO (2013) FAO Statistical databases (FAOSTAT). http://faostat3.fao.org/faostat-gateway/go/to/home/E

Fisher JM, Ripperger RJ, Kimball SM, Bloomberg AM (2002) S, S, S-Tributyl phosphorotrithioate washoff and dissipation of foliar residues. In: Phelps W, Winton K, Effland WR (eds) Pestic Environ Fate. American Chemical Society, Washington, pp 143–151

Fryer ME, Collins CD (2003) Model intercomparison for the uptake of organic chemicals by plants. Environ Sci Technol 37:1617–1624

Ganzelmeier H, Rautmann D, Spangenberg R, Streloke M, Herrmann M, Wenzelburger H-J, Walter H-F (1995) Studies on the spraydrift of plant protection products. 111

Garratt JA, Kennedy A, Wilkins RM, Ureña-Amate MD, González-Pradas E, Flores-Céspedes F, Fernández-Perez M (2007) Modeling pesticide leaching and dissipation in a Mediterranean littoral greenhouse. J Agric Food Chem 55:7052–7061

Geisler G, Hellweg S, Liechti S, Hungerbühler K (2004) Variability assessment of groundwater exposure to pesticides and its consideration in life-cycle assessment. Environ Sci Technol 38:4457–4464

Gil Y, Sinfort C (2005) Emission of pesticides to the air during sprayer application: a bibliographic review. Atmos Environ 39:5183–5193

Gil Y, Sinfort C, Brunet Y, Polveche V, Bonicelli B (2007) Atmospheric loss of pesticides above an artificial vineyard during air-assisted spraying. Atmos Environ 41:2945–2957

Gil Y, Sinfort C, Guillaume S, Brunet Y, Palagos B (2008) Influence of micrometeorological factors on pesticide loss to the air during vine spraying: data analysis with statistical and fuzzy inference models. Biosyst Eng 100:184–197

Goedkoop M, Heijungs R, Huijbregts MAJ, De Schryver A, Struijs J, van Zelm R, Ministry of Housing SP and E (VROM) (2012) ReCiPe 2008 - A life cycle impact assessment method which comprises harmonised category indicators at the midpoint and the endpoint level, 1st edition revised. Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment (VROM)

González JJ, Oriol Magrans J, Alonso-Prados JL, García-Baudín JM (2001) An analytically solved kinetic model for pesticide degradation in single compartment systems. Chemosphere 44:765–770

Guth JA, Reischmann FJ, Allen R, Arnold D, Hassink J, Leake CR, Skidmore MW, Reeves GL (2004) Volatilisation of crop protection chemicals from crop and soil surfaces under controlled conditions—prediction of volatile losses from physico-chemical properties. Chemosphere 57:871–887

Harris GL, Catt JA, Bromilow RH, Armstrong AC (2000) Evaluating pesticide leaching models: the Brimstone Farm dataset. Agric Water Manag 44:75–83

Hellweg S, Geisler G (2003) Life cycle impact assessment of pesticides: when active substances are spread into the environment. Zurich, 27 March 2003. Int J Life Cycle Assess 8:310–312

Holterman HJ, Van De Zande JC, Porskamp HAJ, Huijsmans JFM (1997) Modelling spray drift from boom sprayers. Comput Electron Agric 19:1–22

Huber A, Bach M, Frede H (1998) Modeling pesticide losses with surface runoff in Germany. Sci Total Environ 223:177–191

Inao K, Ishii Y, Kobara Y, Kitamura Y (2003) Landscape-scale simulation of pesticide behavior in river basin due to runoff from paddy fields using pesticide paddy field model (PADDY). J Pestic Sci 28:24–32

Jolliet O, Margni M, Charles R, Humbert S, Payet J, Rebitzer G, Rosenbaum RK (2003) IMPACT 2002+: a New life cycle impact assessment methodology. Int J Life Cycle Assess 8:324–330

Juraske R, Antón A, Castells F, Huijbregts MAJ (2007) Human intake fractions of pesticides via greenhouse tomato consumption: comparing model estimates with measurements for captan. Chemosphere 67:1102–1107

Juraske R, Castells F, Vijay A, Muñoz P, Antón A (2009) Uptake and persistence of pesticides in plants: measurements and model estimates for imidacloprid after foliar and soil application. J Hazard Mater 165:683–689

Kah M, Beulke S, Brown CD (2007) Factors influencing degradation of pesticides in soil. J Agric Food Chem 55:4487–4492

Kellogg R, Nehring R, Grube A, Goss D, Plotkin S (2002) Environmental indicators of pesticide leaching and runoff from farm fields. In: Ball VE, Norton G (eds) Agric. Product. SE - 9. Springer US, pp 213–256

Kruijne R, Tiktak A, Van Kraalingen D, Boesten JJTI, Van Der Linden AMA (2004) Pesticide leaching to the groundwater in drinking water abstraction areas. Alterra Rep 41

Kubiak R, Muller T, Maurer T, Eichhorn KW (1995) Volatilization of pesticides from plant and soil surfaces—field versus laboratory experiments. Int J Environ Anal Chem 58:349–358

Lacas J, Voltz M, Gouy V, Carluer N, Gril J (2005) Using grassed strips to limit pesticide transfer to surface water: a review. Rev Lit Arts Am 25:253–266

Larsson MH, Jarvis NJ (2000) Quantifying interactions between compound properties and macropore flow effects on pesticide leaching. Pest Manag Sci 56:133–141

Lebeau F, Verstraete A, Stainier C, Destain MF (2011) RTDrift: a real time model for estimating spray drift from ground applications. Comput Electron Agric 77:161–174

Leistra M, Smelt JH, van den Berg F (2005) Measured and computed volatilisation of the fungicide fenpropimorph from a sugar beet crop. Pest Manag Sci 61:151–158

Leterme B (2006) Assessing pesticide leaching at the regional scale: a case study for atrazine in the Dyle catchment. Université catholique de Louvain

Lin CY, Chou WC, Lin WT (2002) Modeling the width and placement of riparian vegetated buffer strips: a case study on the Chi-Jia-Wang stream, Taiwan. J Environ Manage 66:269–280

Liu W, Gan JJ, Lee S, Kabashima JN (2004) Phase distribution of synthetic pyrethroids in runoff and stream water. Environ Toxicol Chem 23:7–11

Loll P, Moldrup P (2000) Stochastic analyses of field-scale pesticide leaching risk as influenced by spatial variability in physical and biochemical parameters. Water Resour Res 36:959–970

Madrigal I, Benoit P, Barriuso E, Réal B, Dutertre A, Moquet M, Trejo M, Ortiz L (2007) Pesticide degradation in vegetative buffer strips: grassed and tree barriers. Case of isoproturon. Agrociencia MEX 41:205–217

Margni M, Jolliet O, Crettaz P (2002) Life cycle assessment of pesticides on human health and ecosystems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 93:379–392

Matthews GA, Piggott S (1999) Can farmers reduce spray drift? Pestic Outlook 10:31–33

Miao Z, Cheplick M, Williams M, Trevisan M, Padovani L, Gennari M, Ferrero A, Vidotto F, Capri E (2003) Simulating pesticide leaching and runoff in rice paddies with the RICEWQ-VADOFT model. J Environ Qual 32:2189–2199

Nemecek T, Kägi T (2007) Life cycle inventories of agricultural production systems. 308

NREL (2012) U.S. Life Cycle Inventory Database. In: Natl. Renew. Energy Lab. https://www.lcacommons.gov/nrel/search. Accessed 19 Nov 2012

Numabe A, Nagahora S (2006) Estimation of pesticide runoff from paddy fields to rural rivers. Water Sci Technol 53:139–146

Panichelli L, Dauriat A, Gnansounou E (2008) Life cycle assessment of soybean-based biodiesel in Argentina for export. Int J Life Cycle Assess 14:144–159

Passeport E, Benoit P, Bergheaud V, Coquet Y, Tournebize J (2011) Selected pesticides adsorption and desorption in substrates from artificial wetland and forest buffer. Environ Toxicol Chem 30:1669–1676

Paul H, Illing A (1997) Review: the management of pesticide exposure in greenhouses. Indoor Built Environ 6:254–263

Pennington DW, Margni M, Ammann C, Jolliet O (2005) Multimedia fate and human intake modeling: spatial versus nonspatial insights for chemical emissions in western Europe. Environ Sci Technol 39:1119–1128

Persicani D (1996) Pesticide leaching into field soils: sensitivity analysis of four mathematical models. Ecol Model 84:265–280

Phong TK, Vu SH, Ishihara S, Hiramatsu K, Watanabe H (2011) Exposure risk assessment and evaluation of the best management practice for controlling pesticide runoff from paddy fields. Part 2: model simulation for the herbicide pretilachlor. Pest Manag Sci 67:70–76

Rein A, Legind CN, Trapp S (2011) New concepts for dynamic plant uptake models. SAR QSAR Environ Res 22:191–215

Rosenbaum RK, Bachmann TMK, Gold LS, Huijbregts MAJ, Jolliet O, Juraske R, Koehler A, Larsen HF, MacLeod M, Margni M, McKone TE, Payet J, Schuhmacher M, Van de Meent D, Hauschild MZ (2008) USEtox—the UNEP/SETAC-consensus model: recommended characterisation factors for human toxicity and freshwater ecotoxicity in life cycle impact assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess 13:532–546

Rosenbom AE, Kjær J, Henriksen T, Ullum M, Olsen P (2009) Ability of the MACRO model to predict long-term leaching of metribuzin and diketometribuzin. Environ Sci Technol 43:3221–3226

Rüdel H (1997) Volatilisation of pesticides from soil and plant surfaces. Chemosphere 35:143–152

Scholtz MT, Voldner E, McMillan AC, Van Heyst BJ (2002) A pesticide emission model (PEM) part I: model development. Atmos Environ 36:5005–5013

Schriever CA, Von Der Ohe PC, Liess M (2007) Estimating pesticide runoff in small streams. Chemosphere 68:2161–2171

Sexton AM, Shirmohammadi A, Montas H, Gish TJJW (2000) Pesticide loss in surface runoff under various tillage and pesticide formulation conditions. 2000 ASAE Annu. Int. Meet. Milwaukee Wisconsin USA 912 Jul 2000

Siebers J, Binner R, Wittich K-P (2003) Investigation on downwind short-range transport of pesticides after application in agricultural crops. Chemosphere 51:397–407

Smith CN, Carsel RF (1984) Foliar washoff of pesticides (FWOP) model: development and evaluation. J Environ Sci Heal 19:323–342

Sorensen PB, Mogensen BB, Gyldenkaerne S, Rasmussen AG (1998) Pesticide leaching assessment method for ranking both single substances and scenarios of multiple substance use. Chemosphere 36:2251–2276

Teske ME, Bird SL, Esterly DM, Curbishley TB, Ray SL, Perry SG (2002) AgDrift®: a model for estimating near-field spray drift from aerial applications. Environ Toxicol Chem 21:659–671

Teske ME, Miller PCH, Thistle HW, Birchfield NB (2009) Initial development and validation of a mechanistic spray drift model for ground boom sprayers. Trans ASABE 52:1089–1097

Thuyet DQ, Jorgenson BC, Wissel-Tyson C, Watanabe H, Young TM (2012) Wash off of imidacloprid and fipronil from turf and concrete surfaces using simulated rainfall. Sci Total Environ 414:515–524

Trapp S, McFarlane JC (1995) Plant contamination. Modeling and simulation of organic chemical processes. Lewis, Boca Raton

US EPA (1999) Chapter 9: food and agricultural industries, AP 42, Fifth Edition, Volume I

Van den Berg F, Bedos C, Leistra M (2008) Volatilisation of pesticides computed with the PEARL model for different initial distributions within the crop canopy. In: Alexander LS, Carpenter PI, Cooper SE et al. (eds) Int. Adv. Pestic. Appl. Robinson Coll. Cambridge, UK, 9–11 January 2008. Association of Applied Biologists, Wellesbourne, UK, pp 131–138

Van Zelm R, Huijbregts MAJ, Van de Meent D (2009) USES-LCA 2.0—a global nested multi-media fate, exposure, and effects model. Int J Life Cycle Assess 14:282–284

Van Zelm R, Larrey-Lassalle P, Roux P (2014) Bridging the gap between life cycle inventory and impact assessment for toxicological assessments of pesticides used in crop production. Chemosphere 100:175–181

Vanderborght J, Kuhr P, Tiktak A, Wendland F, Vereecken H (2010) Nation-wide assessment of pesticide leaching to groundwater in Germany: comparison of indicator and metamodel approaches. Geophys Res Abstr 12:7734

Vanderborght J, Tiktak A, Boesten JJTI, Vereecken H (2011) Effect of pesticide fate parameters and their uncertainty on the selection of “worst-case” scenarios of pesticide leaching to groundwater. Pest Manag Sci 67:294–306

Wang M, Rautmann D (2008) A simple probabilistic estimation of spray drift—factors determining spray drift and development of a model. Environ Toxicol Chem 27:2617–2626

Willis GH, McDowell LL, Southwick LM, Smith S (1994) Azinphosmethyl and fenvalerate washoff from cotton plants as a function of time between application and initial rainfall. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 27:115–120

Wolters A, Leistra M, Linnemann V, Smelt JH, van den Berg F, Klein M, Jarvis N, Boesten JJTI, Vereecken H (2003) Pesticide volatilisation from plants: improvement of the PEARL, PELMO and MACRO Models. In: DelRe AAM (ed) Proc. 12. Symp. Pestic. Chem. June 4–6, 2003, Piacenza, Ital. Istituto di Chimica Agraria ed Ambientale, Sezione Vegetale, Piacenza, Piacenza, Italy, pp 985–994

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by Syngenta and the TOX-TRAIN project (EU Grant Agreement no. 285286), which was used for the organisation of the workshop and the open-access publication of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Michael Z. Hauschild

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 293 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenbaum, R.K., Anton, A., Bengoa, X. et al. The Glasgow consensus on the delineation between pesticide emission inventory and impact assessment for LCA. Int J Life Cycle Assess 20, 765–776 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-015-0871-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11367-015-0871-1