Abstract

Solid lubricants such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) are used in rolling-element bearings (REBs) when conventional lubrication (i.e. by fluids or greases) cannot be applied owing to extreme operating conditions (e.g. high temperatures or vacuum). Often a double transfer film mechanism is used with a cage acting as a lubricant reservoir resupplying the REB with solid lubricant by cage wear. An increase in service life of such bearings requires a better understanding of the transfer processes in the sliding and rolling contacts. Here, we investigate the effect of PTFE resupply on friction and lubricant film formation in a steel/steel and steel/glass rolling contact by tribometry and classical molecular dynamics (MD). A ball-on-disk tribometer is enhanced by a pin-on-disk sliding contact that transfers PTFE to the disk. The experiment allows simultaneous in situ measurement of friction and film thickness by white light interferometry in the rolling point contact. Increasing the pin load results in an increased PTFE film thickness in the rolling contact accompanied by a significant decrease in friction. To elucidate the observed film transfer and friction mechanism, sliding MD simulations with a newly developed density-functional-based, non-reactive force field for PTFE-lubricated iron oxide surfaces are performed. A strong adhesion of PTFE chains to iron oxide drives transfer film formation, whilst shear-induced chain alignment within PTFE results in reduced friction. The simulations reveal an anti-correlation between PTFE film thickness and friction coefficient—in agreement with the experiments. These investigations are a first step towards methods to control PTFE transfer film formation in REBs.

Graphic Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Rolling-element bearings (REBs) are commonly lubricated with oils or greases to ensure low friction and wear losses. However, these conventional lubricants fail under extreme conditions, for instance due to their volatility and instability at elevated temperatures or under vacuum operation. Under such circumstances, solid lubrication of REBs is considered a viable alternative [1,2,3]. In recent years, several groups studied the behaviour of REBs lubricated by pure PTFE or PTFE composites [4, 5]. Unfortunately, attempts to lubricate a REB with an initially applied PTFE layer fails, since the latter is removed within short time by high pressure and shear in the rolling contacts [6]. Consequently, another lubrication concept is required. By constantly resupplying PTFE using the double transfer mechanism, an effective and durable lubrication of a rolling contact can be achieved [7]. Several authors report REBs with double transfer film PTFE lubrication of the contacts between rolling elements and races [4, 5, 8]. From the cage, which is manufactured from the polymer or its composites, material is transferred to the rolling elements, which in turn transfer material to the inner and outer races [8].

In order to optimize PTFE lubrication of REBs, a detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying double transfer film lubrication in highly loaded rolling contacts is required. To achieve this, two separate processes have to be elucidated: (a) the formation of the transfer films from a sacrificial PTFE reservoir (e.g. the cage) and (b) the lubrication of the roller-element/race contacts by the PTFE transfer films. Process (a) has been addressed in several experimental studies that were conducted on the transfer mechanisms attributed to PTFE in sliding contacts with a single counter body [9, 10] The low friction coefficient of PTFE sliding on a surface results from transfer film formation on the counter surface as well as from chain reorientation at the sliding interface [9]. The formation of the transfer film is affected by the physical properties of the counter surface. For instance, the average roughness [11] or surface texturing [12] can have a great impact on the formation of the transfer film. There is a general consensus about the observation that in sliding PTFE/steel contacts the friction coefficient decreases whilst the wear rate increases with increasing contact pressure [9, 10, 13].

Interestingly, little attention has been paid to process (b), namely the lubrication in a highly loaded point contact with a PTFE transfer film confined between two counter surfaces. Neither the spatial distribution nor the characteristic thickness of the confined film nor the velocity accommodation mode within the PTFE are known. The aim of this article is to close this gap by elucidating the nano-tribological processes in PTFE-lubricated rolling contacts using a combination of experiments in model contacts and classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. An enhancement of a classical ball-on-disk tribometer allows simultaneous in situ measurements of the friction coefficient and the film thickness in a rolling contact. The film thickness is measured by white light interferometry (WLI), which is a well-established method for fluid lubricants [14]. Although WLI has already been used to measure the film thickness of PTFE transfer films [15], this is the first time that it is applied for the in situ observation of the PTFE film in a rolling contact. Our experimental setup allows to display the spatial PTFE distribution within the contact region and provides an accurate measure for the central film thickness in the rolling contact. This film thickness is used as an input parameter for MD sliding simulations.

Atomistic simulations of PTFE systems have emerged in the past 15 years as a valuable tool to provide insights into their tribological behaviour [16, 17]. In particular, the orientation of the PTFE chains was found to play a crucial role for their frictional response [17]. So far, most atomistic simulations have considered pure PTFE systems [16,17,18,19], with only few exceptions investigating PTFE in contact with other materials [20, 21]. Despite the technological relevance of PTFE-lubricated steel contacts, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one very recent classical MD study in the literature that deals with the tribology of PTFE in contact with iron oxide [22]—a model frequently used for steel surfaces in atomistic simulations [23]—and there is no study that explicitly simulates the transfer and transport of PTFE in such contacts. One possible reason for this could be the lack of a suitable force field to describe the interaction between iron oxide and PTFE. In this work, we develop a density-functional-theory-based force field that is specifically tailored for the present tribological situation. Using this newly developed force field, we perform MD simulations that show how shear deformation induces structural transformations within PTFE resulting in alignment of PTFE chains that minimizes the shear stress. Moreover, we demonstrate that the PTFE—α-Fe2O3 adhesion is strong enough to ensure that PTFE sticks to both surfaces of a PTFE-lubricated α-Fe2O3 contact upon separation of the two surfaces. Explicit simulations of the transfer of PTFE from the pin to the contact show that this enables the resupply of PTFE in the ball-disk contact. Finally, we rationalize the experimentally observed relation between film thickness and friction coefficient by explicitly calculating the friction coefficients for varying amounts of PTFE in the contact.

2 Material and Methods

2.1 Experimental Setup

To study the friction and PTFE transfer film formation in a rolling point contact, we modified a ball-on-disk tribometer (EHD2, PCS Instruments). The sketch of the tribometer in Fig. 1 illustrates the experimental setup.

Schematic experimental setup: in the contact between a pin and a rotating glass disk, a PTFE transfer film is created in the sliding track. A steel ball runs on the transfer film and develops a ball running track within the sliding track. The effect of this lubrication mechanism is examined by friction and film thickness measurements in the rolling point contact

The original tribometer with a polished steel ball (diameter 19.05 mm) loaded against a steel or a glass disk is extended by a PTFE pin that acts as a solid lubricant reservoir. The pin has a diameter of 4.3 mm and is also loaded against the disk with a force \({F}_{\mathrm{Pin}}\), which is varied between 0 and 100 N (corresponding to 0–6.9 MPa). For each experiment, a new polished steel ball, a new PTFE pin and a new track on the disk are used. An electronically controlled system loads the steel ball against the disk with a force \({F}_{\mathrm{Ball}}=\) 20 N\(\pm 0.2\). The roughness and the elastic material properties of the specimens sourced from PCS Instruments are provided in Table 1. Using these values and Hertzian theory, the pressure in the rolling point contact can be estimated to be about 526 MPa. With the given test rig, it is possible to measure the friction coefficient and PTFE film thickness in situ during operation. The friction coefficient can be calculated from the measured torque at the ball drive shaft. For a constant pin load, the maximal standard deviation of the friction coefficient is 7.4% of the mean value. The film thickness is measured by the principle of WLI, which is described in detail in Ref. [14] and shortly summarised here for the reader’s convenience. White light is focused by an optic through the glass disk onto the rolling contact and is split into two parallel beams at a semi-transparent chromium layer. One beam is reflected at the chromium layer whilst the other travels through a SiO2 spacer layer and the PTFE film to the surface of the steel ball, where it is reflected. The additional SiO2 layer increases the distance travelled and thus ensures a sufficiently large path difference for interference, which is otherwise limited by the wavelength of the light. Depending on the phase offset, refractive indices and interference order, the thickness of the lubricating film is determined by identifying the wavelength of greatest gain.

Before each measurement, ball and disk are cleaned with acetone. Then, an initial PTFE layer is created on the disk by loading the PTFE pin against the glass disk (rotating with a speed of 400 mm/s) for 15 min. Thereafter, the ball is positioned in the clearly visible sliding track of the pin and is pressed against the glass disk. For all measurements, the ball was placed on a disk radius between 36 and 42 mm. Both the ball and the disk are driven at constant circumferential speeds of 380 mm/s and 420 mm/s, respectively. Consequently, the rolling speed is 400 mm/s and the slide-roll-ratio is 10%. The ambient temperature is 23 °C. Each measurement is performed three times to ensure reproducibility.

2.2 Atomistic Sliding Simulations

The following two types of classical MD sliding simulations are performed.

-

(i)

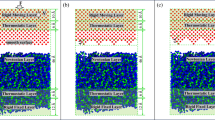

To study structural transformations within a PTFE lubrication layer, we simulate the sliding of a α-Fe2O3 (0001)/PTFE/α-Fe2O3 (0001) contact (Fig. 2a). The hematite surfaces are either Fe- or OH-terminated and slide along the \([10\overline{1 }0]\) direction at constant pressure \({P}_{n}\). After initial temperature and pressure equilibration, an upper 4-Å-thick atoms layer is driven rigidly at constant velocity \({v}_{x}\) whilst the atomic positons of a lower rigid layer with the same height are kept fixed. The normal load of the system is controlled using the pressure-coupling algorithm described in Ref. [25]. During sliding the forces on the upper rigid layer are recorded and their sum is divided by the lateral surface area—resulting in the frictional shear stress experienced by the tribosystem.

-

(ii)

Transfer and transport of PTFE are studied by shear simulations of a PTFE block sliding against an iron oxide surface (Fig. 2b). In these simulations a Fe- or OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) slab is brought into contact with a PTFE slab (mimicking the PTFE pin—disk contact) with a constant velocity \({v}_{z}\) applied to an upper rigid atomic layer (thickness 4 Å) that is simultaneously driven at a constant velocity \({v}_{x}\). A 2-nm-thick layer at the bottom of the PTFE slab is kept fixed. After reaching a normal load of 100 MPa, \({v}_{z}\) is inverted and the system is separated. Afterwards, in an analogous way, the resulting (now PTFE-covered) α-Fe2O3 (0001) slab is brought into contact with a second α-Fe2O3 (0001) slab and separated again (mimicking the ball—disk contact).

a Setup for the MD sliding simulations under a normal load \({P}_{n}\). The upper rigid layer is driven at constant velocity \({v}_{x}\), whilst the lower rigid layer is kept fixed. b Setup for the MD transport simulations, where a α-Fe2O3 (0001) slab approaches a PTFE slab with constant velocity vz. Once the system reaches a target normal pressure Pn, vz is inverted and the system is separated. H, O, Fe, C, F atoms are shown as white, red, brown, grey and green spheres, respectively (Color figure online)

In both types of simulations the α-Fe2O3 (0001) slabs consist of 12,960 atoms in the Fe-terminated case and of 13,392 atoms in the OH-terminated case, resulting in a slab size of \(6.086\times 5.270\times 4.3\) nm3. Atoms in 5-Å-thick regions adjacent to the rigid layers are thermalized using Langevin thermostats with a time constant \(\tau =1\) ps and a target temperature of 300 K. Thermalization is only performed in the direction normal to the loading and the sliding directions. The equations of motion are integrated using at time step of 0.5 fs. Periodic boundary conditions are applied in the interface plane directions. Details of the interatomic interactions are given in the Appendix. All classical MD simulations are carried out with LAMMPS [26].

The boundary conditions for the simulations are chosen to be comparable to the experimental conditions whenever possible. Besides the temperature and the PTFE film thickness, this includes the magnitude of the contact pressures: A ball load of 20 N corresponds to a Hertzian pressure of 526 MPa for the material properties given in Table 1, the normal loads \({P}_{n}\) used in the simulations range between 100 MPa and 1 GPa. In contrast, due to computational time scale limitations a direct match is not possible for the sliding velocity and a comparison to the experimental shear stresses is only possible on a qualitative level. However, the structural transformations observed within PTFE are mechanically rather than thermally induced, i.e. they predominantly depend on the sliding distance \(s\) rather than on speed \({v}_{x}\) or time \(t\) [27]. In other words, simulations with high sliding velocity deliver the same results regarding shear-induced structural transformations as simulations with lower sliding velocity as long as the sliding distance (\(s={v}_{x}t\)) remains the same [28, 29] (see Appendix).

The PTFE in our tribosystems is represented by an all-atom oligomer model. This choice is motivated by a previous study with polyether ether ketone [30] showing that the mechanical and tribological response of a thermoplastic polymer can be reasonably described by finite chains. To create an amorphous PTFE sample, we initially randomize 400 C40F82 PTFE oligomer molecules at 1500 K using a Langevin thermostat with time constant \(\tau =1\) ps for 1 ns within a simulation box with fixed volume corresponding to a density of 0.1 g/cm3. As boundary condition in the direction \(z\) normal to the designated sliding interfaces, we use two purely repulsive harmonic walls separated by 23.2 nm. Atoms whose distances to walls \(r<{r}_{c}\) interact with the wall via a parabolic potential \({E}_{\mathrm{wall}}={K}_{\mathrm{wall}}{\left(r-{r}_{c}\right)}^{2}\), where \({r}_{c}\) = 0.1 nm and the spring constant is \({K}_{\mathrm{wall}}=20\) eV/Å2. Periodic boundary conditions are used in the \(xy\) plane. Afterwards, the cell size in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions is linearly decreased to achieve a final density of 1.5 g/cm3 within 0.5 ns whilst the \(z\) coordinates of the walls are kept fixed. In a third step, the system is equilibrated at 500 K and the cell is allowed to relax in the \(xy\) plane using a Berendsen barostat with target pressure \(0\) for 3 ns. Finally, the temperature of the system is linearly decreased to 0 K with a rate of 0.25 K/ps and the sample is relaxed.

3 Results

In this section, we present the results of the experimental measurements and of the MD simulations. We first focus on the influence of sliding time and pin load on friction coefficient and film thickness of a PTFE-lubricated rolling point contact. Next, the atomistic mechanisms within the sliding and rolling contacts are clarified by means of the MD simulations.

3.1 Friction and Film Thickness Measurements

During a running-in phase, the PTFE pin slides on the disk with a pin load of 80 N and a velocity of 400 mm/s to create an initial transfer film. For the subsequent measurements, the steel ball is loaded against the disk with 20 N. The transient friction coefficients are shown for the contact between the steel ball and a steel disk in Fig. 3a and between the steel ball and a SiO2-coated disk in Fig. 3b. Within the first 500 s, the PTFE pin load is kept at 80 N to constantly resupply the rolling contact. For both disks (steel or coated glass) the measured friction coefficients have average values of 0.026. When the PTFE pin is removed, the friction coefficient measured on the steel disk shows a gradual rise and reaches within 400 s a constant value of 0.07, whilst it immediately increased to a steady state value of 0.056 for the glass disks.

Evolution of coefficient of friction and lubricant film thickness in a rolling ball-on-disk contact when the PTFE pin load changes from 80 to 0 N; a coefficient of friction in the steel/steel contact, b coefficient of friction in steel/glass contact, c central film thickness in the steel/glass contact

The transient values of the central film thickness measured during an experiment on the glass disk are presented in Fig. 3c. When the rolling contact is resupplied with PTFE by the pin sliding on the disk within the first 500 s, the central film thickness values scatter in the range between 5 and 64 nm with an average of 23.9 nm \(\pm 1.9\). When the PTFE pin is removed after 500 s, the film thickness decreases to an average of 12.5 nm \(\pm 1.0\) with values ranging between 2 and 49 nm. Even though the scattering between the data points is high, the average values of the film thickness suggest a clear influence of the pin load.

Figure 4 shows WLI images of the rolling point contact between a glass disk and a steel ball at a ball load of \({F}_{\mathrm{Ball}}=\) 20 N. From these images, the film thickness is calculated using the spacer layer imaging method (SLIM) described in Ref. [31]. The circular area represents the contact region and the interference patterns indicate the increase of the gap height between disk and ball outside the contact. The colours in the contact zone can be correlated to the PTFE film thickness. The WLI image of an unlubricated contact at zero speed serves as a reference (presented in Fig. 4a). Although the PTFE film thickness is zero here, the distance between the semi-reflective chromium layer and the reflective ball surface is equal to the SiO2 spacer layer thickness, resulting in the light blue colour. Figures 4b–e show the film formation in the rolling contact at a rolling speed of 400 mm/s when PTFE is resupplied with a pin load of 80 N. The colours in the contact region vary from blue to yellow and red, indicating an inhomogeneous film thickness within the contact zone ranging between 0 and 40 nm. When the load on the PTFE pin is removed, the colour in the contact zone is light blue to yellow, indicating a more homogeneous PTFE film with a thickness of few nanometres (Fig. 4f–h). The interference patterns in rolling direction in the lower part of Fig. 4f–h indicate the formation of side bands next to the ball running track with a thickness of more than a micrometre.

WLI images of ball/disk contact at a ball load of 20 N and a slide-roll ratio of 10%: a reference of an unlubricated contact at vRoll = 0 mm/s captured before measurement; b–e the film formation at vRoll = 400 mm/s and FPin = 80 N is inhomogeneous within the contact cross section and varies within the measurement intervals of 500 s; f–h the film formation at vRoll = 400 mm/s and FPin = 0 N is more homogeneous and shows PTFE residues even without relubrication

To determine the effect of the PTFE quantity which is transferred from pin to disk, the pin load is increased stepwise from 0 to 100 N. Each step has a duration of 500 s, during which the pin load is kept constant whilst friction and film thickness are measured every 5 s. From all measured values of the friction coefficient and film thickness recorded within a single load step an average value is calculated. In Fig. 5 these averages are shown as a function of the pin load. Whilst especially the film thickness values scatter strongly, as can be seen in Fig. 3c, the resulting averages are highly reproducible, indicated by the error bars obtained as standard error of the mean of three independent measurements. The average friction coefficient decreases from 0.048 at a pin load of 0 N to 0.025 at pin load of 80 N. At a pin load of 100 N, the friction coefficient is slightly higher compared to the value at 80 N. The film thickness increases from 7 nm at 0 N pin load to 22 nm at 100 N pin load.

3.2 Simulation Results

Non-reactive MD simulations are performed to gain atomic-scale insights into the tribology of PTFE-lubricated steel contacts and to investigate the transfer of PTFE films on steel. We start by considering PTFE between two Fe-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces (Fig. 6a). Following Ref. [23], these surfaces are chosen as representative models of oxidised steel surfaces. In order to assess the influence of the surface chemical termination on the tribological properties of the PTFE/steel system, additional simulations with hydroxylated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces are conducted. The PTFE-lubricated model system is obtained by inserting the 21-nm-thick, amorphous PTFE slab (modelled with 400 C40F82 oligomers; see Sect. 2.2) between two α-Fe2O3 (0001) slabs. Even though PTFE is typically semi-crystalline a purely amorphous sample is considered as a limit case to explore whether shear can result in ordering of the molecules [30].

a Snapshot of the α-Fe2O3/PTFE/α-Fe2O3 system prior to sliding. b Snapshots of the system after 22 ns sliding at a normal load \({P}_{n}=100\) MPa. c Time evolution of the shear stress τ (dotted lines, left scale) and average orientation of the molecules (solid lines, right scale) for OH-terminated (green) and Fe-terminated (blue) α-Fe2O3 slabs. The shear stress curves represent a running-average over 0.4 ns. The orientation is measured by the average absolute projection of the normalized carbon–carbon bond vectors on the sliding direction. The upper horizontal solid line indicates the average orientation of a reference simulation with hydroxylated surfaces and a complete alignment of all PTFE molecules prior to sliding. The lower dashed line represents the corresponding shear stress in this reference simulation. d Velocity profile of the PTFE molecules \(v(z)\) for different times for the Fe-terminated case. Each profile is averaged over 0.25 ns (Color figure online)

The PTFE molecules are modelled using the OPLS all-atom force field with the parameters devised by Watkins and Jorgensen [32]. To study the tribological behaviour of PTFE/steel systems, we extend this PTFE interatomic potential by developing a force field for Fe- and OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces and their interaction with PTFE. The force field parameters are fitted to DFT results to accurately describe the elastic response of Fe2O3 and the adsorption of PTFE oligomers on the Fe2O3 surface (as explained in detail in the Appendix).

Upon shearing at \(T=300\) K, with \({P}_{n}=100\) MPa and \({v}_{x}=100\) m/s, for both the Fe- and the OH-terminated systems, we observe a shear-induced alignment of the molecules, which is consistent with the results of other MD studies on similar systems [22, 30], and that results in pseudo-crystalline arrangements reminiscent of the hexagonal Phase II [33] (see snapshots in Fig. 6b and the Supplemental Videos). The spatial extension of the aligned phase grows gradually with time along the \(z\) direction. To quantify the alignment, the C–C bond unit vectors of the molecules are determined and projected on the sliding direction. The average absolute value of this projection is shown as solid lines in Fig. 6c. Whilst initially this value is close to 0.5 (corresponding to the isotropic case), it rapidly increases with time and slowly approaches the fully aligned case (upper dashed lines). Even though we obtain qualitatively identical results for both terminations, the alignment in the OH-terminated case is significantly faster.

To elucidate the faster alignment in the hydroxylated α-Fe2O3 system, we investigate the time evolution of the shear stress (dotted lines in Fig. 6c) and of the PTFE velocity profiles (Fig. 6d). At the onset of sliding, the shear stress in the OH-terminated system is significantly higher than in the Fe-terminated system. The corresponding velocity profile reveals that the shear is localized between the molecules and the surface termination. The lower friction in the Fe-terminated case can be attributed to the atomic-scale smoothness of this surface, whilst hydroxyl groups act as steric obstacles [34] that increase friction in the OH-terminated case. As sliding progresses, the shear deformation becomes localized within the PTFE film and the PTFE/Fe2O3 wall slip disappears. In the OH-terminated case this transition occurs faster due to the larger shear stress and atomic surface roughness. Eventually, as soon as the entire shear stress is accommodated in PTFE, the shear stresses are approximately identical for both surface terminations and are close to the shear stress of entirely aligned PTFE molecules (lower dashed line in Fig. 6c). We note that the alignment of molecules occurs in the region where the shear stress is localized.

Whether a PTFE film transfer from one steel surface to another occurs or not depends on the balance between the molecular cohesion within the PTFE film and the adhesion of the PTFE to the steel surfaces. If PTFE/steel adhesion is weak in comparison to PTFE/PTFE adhesion, the transfer film will likely remain completely on one of the two surfaces, whilst a strong polymer/steel adhesion should results in a partitioning of the PTFE film between the two sliding bodies. To investigate which of the two situations is more likely, we “open” the contacts of Fig. 6c by separating the two oxide slabs with a constant velocity \({v}_{z}=5\) m/s that is added to the upper rigid layer after different times (\({t}_{\mathrm{sep}}\)= 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 ns for both terminations). For all systems, independent of termination and degree of orientation, we observe the formation of free surfaces within PTFE, i.e. both α-Fe2O3 slabs are covered by a PTFE film (see Fig. 7 for final snapshots of separation simulations starting with different \({t}_{\mathrm{sep}}\)). The partitioning of the PTFE between upper and lower α-Fe2O3 slabs is on average approximately 50%/50%, but for individual snapshots sharing of the PTFE layer can be asymmetric (e.g. 32%/68% in Fig. 7b 0 ns). Interestingly, separation of the Fe2O3 surfaces produces cracks that propagates preferentially along the boundary between crystalline and amorphous PTFE phases. Indeed, the crystal-amorphous interface allow for an easy separation given the strong cohesion of both crystalline and amorphous PTFE phases.

Final snapshots of separation simulations of α-Fe2O3/PTFE/α-Fe2O3 systems for the Fe- (a) and OH-terminated case (b). After sliding for a time \({t}_{\mathrm{sep}}\) (Fig. 6c), a constant velocity \({v}_{z}\) is added to the upper rigid layer. Yellow numbers refer to the percentage of PTFE molecules remaining on the lower and upper α-Fe2O3 slabs, respectively (Color figure online)

To more directly mimic the experiment, another series of simulations is performed. We start with an α-Fe2O3 (0001) slab (representing the disk) that slides with a velocity \({v}_{x}=100\) m/s and approaches a PTFE slab (representing the experimental PTFE pin) with \({v}_{z}=5\) m/s. The “pin” is modelled by 400 C40F82 molecules, whilst the disk surface is Fe-terminated (we note however that a hydroxylated “disk” yields the same results). To circumvent the computational burden to simulate the shear-induced alignment of the PTFE oligomers during the running-in phase, the PTFE molecules are pre-aligned in the shear direction. As soon as the normal load of the system reaches 100 MPa, the vertical velocity \({v}_{z}\) is inverted and the system is again separated (see (i)–(iii) in Fig. 8). In agreement with the experiment, there is a significant amount of PTFE that is removed from the “pin” and sticks to the “disk”.

Transfer of the PTFE lubricant from the pin to the ball-disk contact. i A α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface approaches the PTFE pin with \({v}_{z}=5\) m/s whilst sliding with \({v}_{x}=100\) m/s. ii After a normal load \({P}_{n}=100\) MPa is reached \({v}_{z}\) is inverted and the system is separated (iii). iv The resulting PTFE-covered surface is brought into contact with a second α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface again with \({v}_{z}\). Once \({P}_{n}=1\) GPa is reached \({v}_{z}\) is inverted (v) and the contact is opened (vi)

Next, we bring the PTFE-covered “disk” in contact with a second uncovered Fe-terminated α-Fe2O3 surface (the “ball”; note that a hydroxylated “ball” yields the same results) mimicking the formation of the ball-on-disk contact (see (iv)–(vi) in Fig. 8). For this purpose, we use again a sliding velocity \({v}_{x}=100\) m/s and approach the “ball” with \({v}_{z}=5\) m/s. Once the normal load reaches \({P}_{n}=1000\) MPa, we again invert \({v}_{z}\) and separate the system. In agreement with the successful lubrication observed in the experiment now also the “ball” is covered with PTFE.

Interestingly, the experiments showed a decrease of friction with increasing PTFE film thickness (Fig. 5). In our final simulations, this relationship is rationalized by explicitly modelling contacts with 180, 270, 360 and 450 C40F82 molecules (resulting in film thicknesses between 9 and 23 nm) between two OH-terminated slabs. Again, the molecules are pre-aligned with the sliding direction. To somewhat reduce the large velocity gap between the experiment and the simulations, the sliding velocity is set to \({v}_{x}\)=10 m/s and sliding is performed for 3 ns. Figure 9a shows the average velocity profile of the PTFE phase for the different thicknesses when applying a normal load \({P}_{n}=100\) MPa. In all four cases the velocity decreases roughly linearly between the upper and the lower iron oxide slab, i.e. the average shear rate decreases with increasing thickness. To calculate a coefficient of friction in the four cases, additional simulations at \({P}_{n}=250\), \(500\) and \(1000\) MPa are conducted. Figure 9b shows the average shear stress \(\tau\) as a function of the applied normal load \({P}_{n}\). Since there is a clear linear relationship between both quantities, the coefficient of friction can be estimated from the slope of these curves (allowing for an adhesive offset). The resulting coefficients of friction are in good agreement with the experimental values (Fig. 9c). Whilst the exact numerical values should not be over-interpreted, it is crucial that both experiments and simulations show the same trends in the decrease of friction with increasing film thickness suggesting that the reduction of the experimental COF with increasing lubricant film thickness is related with the decrease of the shear rate within the PTFE phase.

a Average PTFE velocity profiles for different PTFE film thicknesses as indicated in the legend. The sliding system consists of C40F82-lubricated, self-mated OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) slabs in relative motion with vx = 10 m/s and \({P}_{n}=100\) MPa. The profiles are averaged over 2 ns. b Average shear stress \(\tau\) as a function of the applied normal load \({P}_{n}\) for 9, 14, 18 and 24 nm thick PTFE films. Solid lines are linear fits to the measured MD data points. c Coefficient of friction estimated from the slope of the fits of (b) as a function of the film thickness (green). The experimental data points from Fig. 5 are shown in blue (Color figure online)

4 Discussion and Conclusion

These results show that a constant external resupply enables an effective PTFE lubrication of highly loaded rolling contacts. Our in situ experiments with SiO2-coated glass disks reveal that the thickness of the PTFE film in the rolling contact can be directly controlled by the pin load. An increase of pin load leads to an increase of transferred PTFE and thus an increase of film thickness in the highly loaded rolling contact. With increasing pin load, and thus increasing film thickness, the friction coefficient decreases to a minimal value of 0.025 at a pin load of 80 N. At a pin load of 100 N, friction losses were higher, which could potentially be explained by the churning losses in a thick PTFE film. Another hypothesis would be the debris formation at the PTFE pin under higher loads, resulting in a transfer of thick PTFE particles. Both hypotheses will be evaluated in further studies. Yet, the analysis of frictional losses and film thickness under the variation of pin load between 0 and 100 N (0–6.9 MPa) suggests that at a pin load of 80 N (5 MPa) is sufficient to completely separate the surfaces in a highly loaded rolling contact for the given operation conditions. It is worth pointing out, that a similar frictional behaviour was observed in experiments with a steel disk, thus making it independent of the material of the disk.

The measured film thickness shows significant scattering in the range of multiple nanometres, which can be attributed to the inhomogeneity of the lubricating film in the rolling contact. In contrast, the friction coefficient shows only small variations after the running-in. This can be explained by the fact that friction is an integral result that can be seen as the sum of local shear stresses within the contact, whereas the film height is measured on a single point in the centre of the contact zone. Future studies will therefore focus on a measurement of the full areal distribution of the film thickness in the contact region. Nevertheless, it can be concluded that the transient and local inhomogeneity of the film formation within the contact region causes scattering of the measured film thickness without detrimental influences on the tribological behaviour.

The transfer film formation of PTFE is possible due to the strong adhesion of PTFE on the steel or glass disk. Our atomistic simulations show that the separation of two PTFE-lubricated α-Fe2O3 surfaces results in the PTFE coverage of both surfaces. We note that in our simulations no chemical reactions are considered between PTFE and the surfaces and adhesion is fully determined by physisorption. PTFE chains that break due to shear forces [35, 36] can chemisorb on the surface which should further enhance the PTFE adhesion on the surfaces and in turn the PTFE transfer film formation.

Furthermore, our simulations show that the arrangement of the molecules is crucial for friction. In particular, shear can disentangle PTFE chains in amorphous regions and induce the alignment of the molecules with the sliding directions. This structural running-in process results in a strong reduction of shear stress. Surprisingly, our MD work also suggests that alignment plays a role in the transfer film formation since the PTFE cleavage surfaces that form upon “contact opening” are localized close to crystal-amorphous interfaces.

Shear deformation in the PTFE layer is accommodated by an approximately linear velocity profile within the crystal-like region. Consequently, a thicker PTFE film consisting of shear-aligned molecules should reduce the shear rate which could explain the friction decrease with increasing film thickness observed in the experiments.

Future work will address the optimization of transfer film formation using PTFE compounds to obtain more homogenous films. Moreover, the friction behaviour and film formation at different operating points will be investigated to determine the operating limits for PTFE-lubricated, highly loaded rolling contacts. Future atomistic studies should also focus on the velocity dependence of PTFE film transfer and friction, since in our shearing simulations velocities are still 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than in the experiments, and on the influence of the PTFE chain length that can affect the time scale on which structural transformations occur.

In general, transfer film formation and friction of solid lubricants are highly complex problems that impede the rational design of double-film-transfer REBs. However, an understanding of the underlying mechanisms can be gained with the presented approach that combines in situ friction and WLI measurements with MD sliding simulations. Hopefully, our work and follow-up studies will pave the way for an improvement of the reliability of solid-lubricated, rolling-element bearings.

Data Availability

The data related to this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Birkhofer, H., Kümmerle, T.: Feststoffgeschmierte Wälzlager. Springer, Berlin (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16797-3

Marquart, M., Sauer, B.: Optimized cage design for increasing the life of solid lubricated roller bearings. In: ASME 2012 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Volume 3: Design, Materials and Manufacturing, Parts A, B, and C. pp. 985–993. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1115/IMECE2012-86239

Marquart, M., Wahl, M., Emrich, S., Zhang, G., Sauer, B., Kopnarski, M., Wetzel, B.: Enhancing the lifetime of MoS2-lubricated ball bearings. Wear 303, 169–177 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2013.03.003

Suzuki, M., Prat, P.: Synergism of an MoS2 sputtered film and a transfer film of a PTFE composite. Wear 225–229, 995–1003 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0043-1648(99)00073-3

Choe, B., Lee, J., Jeon, D., Lee, Y.: Experimental study on dynamic behavior of ball bearing cage in cryogenic environments, part I: effects of cage guidance and pocket clearances. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 115, 545–569 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.06.018

Lu, X., Wong, K.C., Wong, P.C., Mitchell, K.A.R., Cotter, J., Eadie, D.T.: Surface characterization of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) transfer films during rolling–sliding tribology tests using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Wear 261, 1155–1162 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2006.03.020

Fusaro, R.L.: Self-lubricating polymer composites and polymer transfer film lubrication for space applications. Tribol. Int. 23, 105–122 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-679X(90)90043-O

Colas, G., Saulot, A., Michel, Y., Filleter, T., Merstallinger, A.: Experimental analysis of friction and wear of self-lubricating composites used for dry lubrication of ball bearing for space applications. Lubricants 9, 38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants9040038

Biswas, S.K., Vijayan, K.: Friction and wear of PTFE—a review. Wear 158, 193–211 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(92)90039-B

Blanchet, T.A., Kennedy, F.E.: Sliding wear mechanism of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and PTFE composites. Wear 153, 229–243 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(92)90271-9

Lancaster, J.K.: Accelerated wear testing as an aid to failure diagnosis and materials selection. Tribol. Int. 15, 323–329 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-679X(82)90141-4

Ding, L., Axinte, D., Butler-Smith, P., Abdelhafeez Hassan, A.: Study on the characterisation of the PTFE transfer film and the dimensional designing of surface texturing in a dry-lubricated bearing system. Wear 448–449, 203238 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2020.203238

Uchiyama, Y., Tanaka, K.: Wear laws for polytetrafluoroethylene. Wear 58, 223–235 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(80)90152-0

Johnston, G.J., Wayte, R., Spikes, H.A.: The measurement and study of very thin lubricant films in concentrated contacts. Tribol. Trans. 34, 187–194 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1080/10402009108982026

Ye, J., Sun, W., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Liu, K.: Measuring evolution of transfer film-substrate interface using low wear alumina PTFE. Tribol. Lett. 66, 1–14 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-018-1054-6

Barry, P.R., Chiu, P.Y., Perry, S.S., Sawyer, W.G., Phillpot, S.R., Sinnott, S.B.: The effect of normal load on polytetrafluoroethylene tribology. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 21, 144201 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/21/14/144201

Barry, P.R., Chiu, P.Y., Perry, S.S., Sawyer, W.G., Sinnott, S.B., Phillpot, S.R.: Effect of temperature on the friction and wear of PTFE by atomic-level simulation. Tribol. Lett. 58, 50 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-015-0529-y

Brownell, M., Nair, A.K.: Deformation mechanisms of polytetrafluoroethylene at the nano- and microscales. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 490–503 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP05111A

Pan, D., Fan, B., Qi, X., Yang, Y., Hao, X.: Investigation of PTFE tribological properties using molecular dynamics simulation. Tribol. Lett. 67, 28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-019-1141-3

Onodera, T., Nunoshige, J., Kawasaki, K., Adachi, K., Kurihara, K., Kubo, M.: Structure and function of transfer film formed from PTFE/PEEK polymer blend. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 14589–14596 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b02860

Onodera, T., Park, M., Souma, K., Ozawa, N., Kubo, M.: Transfer-film formation mechanism of polytetrafluoroethylene: a computational chemistry approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 10464–10472 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp400515j

Xu, Q., Zhang, J., Hu, Y.-Z., Ma, T.-B.: Tribological behavior of poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) and its composites reinforced by carbon nanotubes and graphene sheets: molecular dynamics simulation. Phys. Status Solidi Rapid Res. Lett. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/pssr.202100298

Latorre, C.A., Ewen, J.P., Gattinoni, C., Dini, D.: Simulating surfactant–iron oxide interfaces: from density functional theory to molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 6870–6881 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b02925

Sauer, J.A., Pae, K.D.: The flow of solid polymers under high pressure. Colloid Polym. Sci. 252, 680–695 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01554493

Pastewka, L., Moser, S., Moseler, M.: Atomistic insights into the running-in, lubrication, and failure of hydrogenated diamond-like carbon coatings. Tribol. Lett. 39, 49–61 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-009-9566-8

Plimpton, S.: Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1995.1039

Moras, G., Klemenz, A., Reichenbach, T., Gola, A., Uetsuka, H., Moseler, M., Pastewka, L.: Shear melting of silicon and diamond and the disappearance of the polyamorphic transition under shear. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 083601 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.2.083601

Kuwahara, T., Romero, P.A., Makowski, S., Weihnacht, V., Moras, G., Moseler, M.: Mechano-chemical decomposition of organic friction modifiers with multiple reactive centres induces superlubricity of ta-C. Nat. Commun. 10, 151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08042-8

Salinas Ruiz, V.R., Kuwahara, T., Galipaud, J., Masenelli-Varlot, K., Hassine, M. Ben, Héau, C., Stoll, M., Mayrhofer, L., Moras, G., Martin, J.M., Moseler, M., de Barros Bouchet, M.-I.: Interplay of mechanics and chemistry governs wear of diamond-like carbon coatings interacting with ZDDP-additivated lubricants. Nat. Commun. 12, 4550 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24766-6

Savio, D., Hamann, J., Romero, P.A., Klingshirn, C., Bactavatchalou, R., Dienwiebel, M., Moseler, M.: Multiscale friction simulation of dry polymer contacts: reaching experimental length scales by coupling molecular dynamics and contact mechanics. Tribol. Lett. 69, 70 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-021-01444-8

Cann, P.M., Spikes, H.A., Hutchinson, J.: The development of a spacer layer imaging method (SLIM) for mapping elastohydrodynamic contacts. Tribol. Trans. 39, 915–921 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1080/10402009608983612

Watkins, E.K., Jorgensen, W.L.: Perfluoroalkanes: conformational analysis and liquid-state properties from ab initio and monte carlo calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 105, 4118–4125 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp004071w

Brown, E.N., Trujillo, C.P., Gray, G.T., Rae, P.J., Bourne, N.K.: Soft recovery of polytetrafluoroethylene shocked through the crystalline phase II–III transition. J. Appl. Phys. 101, 024916 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2424536

Reichenbach, T., Mayrhofer, L., Kuwahara, T., Moseler, M., Moras, G.: Steric effects control dry friction of H- and F-terminated carbon surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 8805–8816 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b18019

Campbell, K.L., Sidebottom, M.A., Atkinson, C.C., Babuska, T.F., Kolanovic, C.A., Boulden, B.J., Junk, C.P., Krick, B.A.: Ultralow wear PTFE-based polymer composites—the role of water and tribochemistry. Macromolecules 52, 5268–5277 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00316

Pitenis, A.A., Harris, K.L., Junk, C.P., Blackman, G.S., Sawyer, W.G., Krick, B.A.: Ultralow wear PTFE and alumina composites: it is all about tribochemistry. Tribol. Lett. 57, 4 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-014-0445-6

Jülich Supercomputing Centre: JUWELS: Modular Tier-0/1 Supercomputer at Jülich Supercomputing Centre. J. Large-Scale Res. Facil. JLSRF. 5, A135 (2019). https://doi.org/10.17815/jlsrf-5-171

Stukowski, A.: Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO—the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/18/1/015012

Larsen, A.H., Mortensen, J.J., Blomqvist, J., Castelli, I.E., Christensen, R., Dułak, M., Friis, J., Groves, M.N., Hammer, B., Hargus, C., Hermes, E.D., Jennings, P.C., Jensen, P.B., Kermode, J., Kitchin, J.R., Kolsbjerg, E.L., Kubal, J., Kaasbjerg, K., Lysgaard, S., Maronsson, J.B., Maxson, T., Olsen, T., Pastewka, L., Peterson, A., Rostgaard, C., Schiøtz, J., Schütt, O., Strange, M., Thygesen, K.S., Vegge, T., Vilhelmsen, L., Walter, M., Zeng, Z., Jacobsen, K.W.: The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 29, 273002 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aa680e

Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J.: Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169

Bunn, C.W., Howells, E.R.: Structures of molecules and crystals of fluoro-carbons. Nature 174, 549–551 (1954). https://doi.org/10.1038/174549a0

Fatti, G., Righi, M.C., Dini, D., Ciniero, A.: First-principles insights into the structural and electronic properties of polytetrafluoroethylene in its high-pressure phase (Form III). J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 6250–6255 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b11631

Berro, H., Fillot, N., Vergne, P.: Molecular dynamics simulation of surface energy and ZDDP effects on friction in nano-scale lubricated contacts. Tribol. Int. 43, 1811–1822 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2010.02.011

Mayrhofer, L., Moras, G., Mulakaluri, N., Rajagopalan, S., Stevens, P.A., Moseler, M.: Fluorine-terminated diamond surfaces as dense dipole lattices: the electrostatic origin of polar hydrophobicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4018–4028 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5b04073

Ovcharenko, R., Voloshina, E., Sauer, J.: Water adsorption and O-defect formation on Fe2O3(0001) surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 25560–25568 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CP05313K

Kresse, G., Joubert, D.: From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758

Blöchl, P.E.: Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953

Dudarev, S.L., Botton, G.A., Savrasov, S.Y., Humphreys, C.J., Sutton, A.P.: Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.57.1505

Perdew, J.P., Burke, K., Ernzerhof, M., Ernzerhof, M.: Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865

Rohrbach, A., Hafner, J., Kresse, G.: Ab initio study of the (0001) surfaces of hematite and chromia: Influence of strong electronic correlations. Phys. Rev. B 70, 125426 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.70.125426

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S., Krieg, H.: A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S., Goerigk, L.: Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21759

Pastewka, L., Moser, S., Gumbsch, P., Moseler, M.: Anisotropic mechanical amorphization drives wear in diamond. Nat. Mater. 10, 34–38 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2902

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniele Savio for initial contributions to the project. We gratefully acknowledge funding by the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) within the SPP 2074 (Project No. MO 879/22-1). Computing time was granted by the John von Neumann Institute for Computing (NIC), and provided on the supercomputer JUWELS at the Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC) (Project hfr04 for the DFT simulations and project hfr014 for the MD simulations) [37], and by the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC and the DFG (Grant No. INST 39/963-1 FUGG).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SvG and TR contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (MP4 38499 kb)

Supplementary file2 (MP4 38385 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A Force Field for the PTFE/α-Fe2O3 System

To accurately describe non-reactive interactions in PTFE-lubricated α-Fe2O3 contacts, we develop a force field that is based on density-functional theory (DFT) simulations and is specifically tailored for our purposes as described in the following.

1.1.1 PTFE

The interaction between and within PTFE molecules is described by the all-atoms force field developed by Watkins and Jorgensen [32]. We find that this model can describe different crystalline PTFE phases with good accuracy (see Table 2). Densities and elastic properties of amorphous PTFE as calculated using this force field are reported in Table 3 for CxF2x+2 molecules with \(x=20, 40, 60.\) The preparation of the samples used to calculate the elastic properties of amorphous PTFE follows the procedure described in the Sect. 2.2. However, in this case, periodic boundary conditions are applied in all three Cartesian directions. The negligible variation of density and elastic properties when \(x\) increases from 40 to 60 supports our choice to model PTFE using C40F82 in this work.

1.1.2 Bulk α-Fe2O3

For bulk α-Fe2O3 we use a model that is similar to the one used by Latorre et al. [23] and by Berro et al. [43]. Based on the relaxed DFT configuration, we use harmonic interactions of the form \({E}_{\mathrm{bond}}={K}_{\mathrm{bond}}{\left(r-{r}_{0}\right)}^{2}\) with spring constant \({K}_{\mathrm{bond}}=1.085\) eV/Å2 between all atomic pairs separated by less than 3.2 Å. The choice of this spring constant allows for a good description of the elastic constants of α-Fe2O3 (see Table 4). The set of equilibrium bond lengths \({r}_{0}\) for all interacting atom pairs is {1.963, 2.122, 2.688, 2.793, 2.896, 2.906, 2.986, 3.055} Å.

1.1.3 Fe-Terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001)

α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces are created by removing the periodic boundary conditions from the bulk sample along the \(z\) direction. Details concerning the surface termination are described below in the technical section about the DFT calculations. To account for the surface relaxation as observed in DFT, each terminating Fe atom is displaced by 0.63 Å towards the surface along the \(z\) direction. Using this geometry, in analogy to the bulk case, all atoms separated by less than 3.2 Å interact via harmonic terms with spring constant \({K}_{\mathrm{bond}}=1.085\) eV/Å2. The set of additional equilibrium bond lengths \({r}_{0}\) compared to the bulk case is {1.779, 3.093, 3.125} Å.

The atomic interactions between PTFE and α-Fe2O3 (0001) are modelled via a Lennard–Jones (LJ) potential

The two-body parameters \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) and \({\sigma }_{ij}\) for atom pairs \(ij\) are expressed as functions of the atomic parameters as \({\varepsilon }_{ij}=\sqrt{{\varepsilon }_{i}{\varepsilon }_{j}}\) and \({\sigma }_{ij}=\sqrt{{\sigma }_{i}{\sigma }_{j}}\) to ensure that the mixing rules are compatible with those adopted by Watkins and Jorgensen. The atomic parameters for C40F82 are taken from Ref. [32], the atomic parameters for α-Fe2O3 (0001) are \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{Fe}}=0.02363\) eV, \(\sigma _{{{\text{Fe}}}} = 2.41\) Å, \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{O}}=0.01031\) eV, and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{O}}= 3.21\) Å. These parameters are obtained by fitting the energy of 500 different configurations of a C8F18 molecule interacting with a α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface (see green curves in Fig. 10a). For each of these different configurations, the molecule and the slab are held rigid using their relaxed DFT geometries. The choice to omit Coulombic interactions between PTFE is physically motivated by the fact that electrostatic interactions only play a minor role for the tribology of perfluorinated carbon compounds [34, 44]. As a test, we verify that the adsorption energy of C8F18 as obtained with a geometry optimization using the force field can reproduce the DFT result (− 0.70 eV in both cases).

a Interaction energy between a C8F18 molecule and a Fe-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface (green) and between a C8F18 molecule and an OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface (blue) for different configurations of the molecule on top of the surface. Energies obtained by DFT are represented by dark colours whilst light colours show the energies measured on the same configurations using the present force field. The different configurations of the molecule include rotations and translations in the surface plane and different distances to the surface. A typical configuration for the OH-terminated case is shown in the inset. b Snapshot of the model used for OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces. The labels are explained in the text. c Energy as a function of the O–H bond length (i), of the H–O–Fe angle (ii) and of the dihedral angle H–O-Fe–O (iii) as obtained by DFT and by the present force field (Color figure online)

1.1.4 OH-Terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001)

To assess how the chemical structure of α-Fe2O3 (0001) surfaces influences our results we also consider the hydroxylated surface (Fig. 10b). The model is adapted from Ref. [45] as discussed in more detail below in the technical section about the DFT simulations. To construct the hydroxylated surface from the bulk cell and mimic the DFT geometry, we remove the periodic boundary conditions along the \(z\) direction to obtain a Fe-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) surface. Each surface Fe atom is displaced by 0.291 Å in the \(z\) direction towards the bulk. Next, we hydroxylate each of these Fe surface atoms by adding OH groups with the following displacement vectors relative to the position of the surface Fe atom: \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{\mathrm{O}}=\left( -\,0.161, -\,0.002, 1.819\right)\) Å and \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{\mathrm{H}1}=\left(-0.248, 0.837, 2.303\right)\) Å (Fig. 10b). Finally, H atoms are added to passivate O atoms in the second O layer with the displacement vector \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{\mathrm{H}2}=\left(-2.781, 0.395, 0.206\right)\) Å relative to the position of the surface Fe atom (Fig. 10b). These numerical values are extracted from the relaxed DFT configurations. Using this geometry, harmonic interactions between all atom pairs that do not contain H atoms and are separated by less than 3.2 Å are introduced—again with \({K}_{\mathrm{bond}}=1.085\) eV/Å2. This procedure yields the set \(\left\{1.826, 1.854, 2.922, 2.931, 3.069\right\}\) Å in addition to the set of equilibrium bond lengths \({r}_{0}\) from the bulk case.

Each H termination is connected to the neighbouring O atom by a harmonic bonding term with \({K}_{\mathrm{bond}}=25.24\) eV/Å2 and \({r}_{0}\) = 0.982 Å. These values are obtained by fits to the distance-energy DFT curves upon elongation and compression of individual O–H bonds whilst keeping all other atomic positions fixed (Fig. 10c). In addition, one harmonic H–O–Fe angle with the functional form \({E}_{\mathrm{angle}}={K}_{\theta }{\left(\theta -{\theta }_{0}\right)}^{2}\) with \({K}_{\theta }=0.601\) eV/rad2 and \({\theta }_{0}=121.58^\circ\) is introduced for each H atom in the top H layer. The numerical values are obtained by fits to reference DFT calculations, where the position of individual H atoms are varied to sample different H–O–Fe angles keeping all bond lengths fixed (Fig. 10c). For each H atom in the lower H layer, three such H–O–Fe angles with the same parameters are introduced. Moreover, since no Lennard–Jones or Coulombic terms are used to model interactions within α-Fe2O3, we additionally add one dihedral interaction involving the atom types H–O–F–O (the latter O being part of the lower layer of hydroxyl groups, Fig. 10c) for each H in the upper hydrogen layer to obtain an energetic barrier for the rotation of the OH group.

The dihedral energy term has the form \({E}_{\mathrm{dihedral}}=\frac{1}{2}{K}_{\phi }[1-\mathrm{cos}\left(2\phi \right)]\) with \({K}_{\phi }=-0.1488\) eV and is obtained by fits to DFT benchmark simulations, in which the corresponding dihedral angle is varied whilst keeping all bond lengths fixed (Fig. 10c).

In analogy to the Fe-terminated case, the interaction between OH-terminated α-Fe2O3 (0001) and PTFE is modelled via LJ interactions (Eq. 1). The atomic LJ parameters for the hydroxyl groups are fitted to the interaction with a C8F18 molecule, whilst the parameters for Fe and the remaining O atoms in the slab remain fixed at the values determined in the Fe-terminated case (see blue curves in Fig. 10). This procedure yields \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{H}}=0.01604\) eV, \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{H}}=2.01\) Å and \({\varepsilon }_{\mathrm{O}2}=0.00507\) eV, and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{O}2}= 3.37\) Å. O2 refers to the oxygen atoms of the hydroxyl groups. Again, we verify that the adsorption energy of C8F18 obtained by geometry optimization using the force field is in good agreement with the DFT result (− 0.39 eV and − 0.38 eV, respectively).

1.2 DFT Simulations

All DFT calculations are performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) [40]. VASP employs a plane wave basis set to represent the valence electrons whereas core electrons are taken into account using the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method [46, 47]. In order to partially correct deficiencies of local and semilocal DFT in describing the strongly correlated d-electrons of Fe the DFT + U formalism is used, where a Hubbard model-like term for the onsite Coulomb interactions is added to the semilocal DFT functional [48]. For the latter, we use the PBE functional [49]. Following previous works using VASP to simulate hematite surfaces [45, 50], we select a value of 4 eV for the effective Hubbard parameter U-J. The energy cutoff defining the plane wave basis set is set to 520 eV for the relaxation of the hematite bulk unit cell and the calculation of the elastic constants and to 400 eV for all other simulations. Reciprocal space integration is performed using a 3 × 3 × 3 Monkhorst–Pack grid for the bulk relaxation and all simulations featuring the hematite slab supercell are \(\Gamma\)-point calculations. A Gaussian smearing of the orbital occupancies with a width of 0.1 eV is used throughout. Long-range dispersion forces are taken into account by Grimme’s D3 method with the PBE parameters as implemented in the VASP code [51, 52]. Antiferromagnetic ordering of the Fe magnetic moments of the hematite ground state as reported in Ref. [50] is imposed for both bulk and slab calculations.

The unit cell of the hematite bulk structure used in this work contains six Fe2O3 layers along the [0001] direction and is repeated twice in the other directions. Relaxation of the structure yields lattice constants of \(a = 5.07\) Å and \(c=13.86\) Å in full agreement with earlier reports [45, 50]. From the bulk unit cell, symmetric \(4\times 2\times 1\) slab models are constructed. The cutting plane is chosen such that the surface top and bottom layers consist of bulk Fe layers with half occupation such that the overall Fe2O3 stoichiometry of the resulting slab is conserved. DFT calculations within a GGA + U approach determined this surface termination to be the most stable one within a wide range of oxygen chemical potentials [50]. The model for the hydroxylated hematite (0001) surface (Fig. 10) is set up following Ref. [45], where DFT simulations using again a GGA + U approach predict dissociative chemisorption of H2O molecules as favourable adsorption mechanism of water on hematite (0001) surfaces. Hydroxlation occurs via the dissociation of water molecules into OH− and H+ ions that subsequently bond to the terminal Fe3+ and surface O2− ions, respectively.

1.3 Velocity Dependence of the Structural Transformations Within PTFE

To investigate whether and how the rearrangement of the PTFE molecules depends on the sliding velocity, we repeat the simulation of Fig. 6c for the OH-terminated case with a velocity of 10 m/s (instead of 100 m/s). The fact that the average orientation is a function of the sliding distance (\(s={v}_{x}t\)) and is approximately independent of the velocity (Fig. 11) suggests that the alignment of the molecules is a mechanically induced process [27, 53].

Average orientation of the PTFE molecules as a function of the sliding distance for the OH-terminated system of Fig. 6c for two different sliding velocities \({v}_{x}\)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

von Goeldel, S., Reichenbach, T., König, F. et al. A Combined Experimental and Atomistic Investigation of PTFE Double Transfer Film Formation and Lubrication in Rolling Point Contacts. Tribol Lett 69, 136 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-021-01508-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-021-01508-9

Keywords

Profiles

- Thomas Reichenbach View author profile

- Florian König View author profile