Abstract

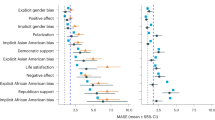

We show that the personal traits of analysts, as revealed by their political donations, influence their forecasting behavior and stock prices. Analysts who contribute primarily to the Republican Party adopt a more conservative forecasting style. Their earnings forecast revisions are less likely to deviate from the forecasts of other analysts and are less likely to be bold. Their stock recommendations also contain more modest upgrades and downgrades. Overall, these analysts produce better quality research, which is recognized and rewarded by their employers, institutional investors, and the media. Stock market participants, however, do not fully recognize their superior ability as the market reaction following revisions by these analysts is weaker.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition, this literature shows that personal political preferences of market participants can affect investment decisions (Bonaparte et al. 2012; Kaustia and Torstila 2011; Hong and Kostovetsky 2012; DeVault and Sias 2014), market prices (Statman and Glushkov 2009; Hong and Kacperczyk 2009), corporate tax avoidance (Christensen et al. 2014), and litigation propensities (Hutton et al. 2015).

Furthermore, various national surveys show that individuals who associate themselves with the Republican Party on both economic and social dimensions tend to have more conservative psychological traits than those who associate themselves with the Democratic Party. See Section II for additional discussion on the potential link between political preferences and conservative personality and psychological traits.

Prior studies show various forecast biases such as nonstrategic excess optimism (Malmendier and Shanthikumar 2014), overweighting of private information (Chen and Jiang 2006), overreaction to favorable information (Easterwood and Nutt 1999), and analysts’ credulity (Teoh and Wong 2002). Thus, our prediction only applies to the relative behavior of conservative analysts versus that of typical analysts, rather than the relative rationality of the two analyst groups.

We also consider and test the alternative explanation that political donations are driven by strategic reasons (see Sect. 7.1) but find little support for this alternative hypothesis.

Hugon and Muslu (2010) find that conservative analysts’ forecasts are more accurate and the stock market reaction to forecast revisions of conservative analysts is stronger on average.

We do not have strong priors about the timing of these conservative forecasts.

A change in forecast is small if the absolute value of the change in earnings forecast is below the average absolute change in forecast revisions made by all other analysts for the same firm in the prior 12 months within the same fiscal year. Similarly, a change in recommendation is small if the upgrade or downgrade for a given firm occurs into an adjacent rating category.

Prior studies show that analysts’ positive opinions about a stock attract investment banking business (e.g., Dechow et al. 2000).

The conservative forecasting style resembles some of the selection criteria cited by fund managers to vote analysts into the All-America research team (e.g., Hugon and Muslu 2010). For example, fund managers frequently cite valuable analysts’ traits as including “not endorsing everything,” “having sober opinions and very little hyperbole,” and “willing to present unpopular perspectives” (Institutional Investor, October 2006).

Prior research finds that market reaction to analyst forecast revisions on average increases with the analyst’s forecast accuracy, although the market may not fully incorporate information about analyst accuracy (Clement and Tse 2003).

Given that our donation data start in 1991 and our earnings forecast data start in 1993, our main sample data based on the merging of these two datasets effectively start in 1993.

Additional details about the FEC data are available in Hutton et al. (2014).

Consistent with our conjecture that political donations are nonstrategic, we find that analysts on average contribute $2,837 to political parties, which is less than the $38,200 average political contribution of a mutual fund manager during the 1992 to 2006 period (Hong and Kostovetsky 2012). The small donations made by sell-side analysts further indicate that analysts’ political donations are unlikely to be strategic in nature but an expression of personal preferences (Ansolabehere et al. 2003).

Hutton et al. (2014) show that about 55 % of top managers including CEOs contribute only to the Republican Party during the 1992 to 2008 sample period.

We hand-collect the gender and age information of analysts from various Internet sources. The age data are available for only a very small fraction of analysts in the sample.

We classify a name as foreign sounding when at least 75 % of the Amazon’s Mechanical Turk workers we hired indicated so. For details of variable construction, please refer to Kumar et al. (2015).

Our results are stronger if we use the Fama and MacBeth (1973) estimation method instead of a panel estimation framework. Our main results are also similar when we use quarterly instead of annual earnings forecasts.

Forecast revision is defined as the change in forecasted earnings per share scaled by the stock price two days prior to the forecast date.

Table 2 shows that 77 % of the forecasts are bold. This is in the same ballpark as the average of 73 % of bold forecasts reported by Clement and Tse (2005). Bold forecasts are opposite to herding forecasts, which move away from an analyst’s own prior forecast and toward the consensus, as defined by Gleason and Lee (2003). As forecast revisions are usually prompted by new information signals, it is not surprising that a majority of revisions are classified as bold.

For a subset of about 200 analysts for whom we have their ages, the correlation between age and general experience is about 0.65.

An earlier study by Clarke, Ferris, Jayaraman, and Lee (2006), however, shows that there is no evidence that the affiliated status influences analysts’ recommendation changes.

Clement and Tse (2005) find that, over a seven-year sample horizon, the odds of observing a bold forecast from an analyst with the highest general experience level are 1.124 times larger than the odds of observing a bold forecast from an analyst with the lowest general experience level.

Similarly, in a study examining buy-side analysts, Brown et al. (2014) confirm that sell-side analysts’ earnings forecasts and stock recommendations are the least useful services they offer to their sophisticated buy-side clients. Moreover, Groysberg et al. (2011) find no evidence that sell-side analysts’ compensation is related to their earnings accuracy. Specifically, their interviews with 11 leading investment banks reveal that “forecast accuracy is not a direct determinant of analyst compensation.” As such, we examine a range of proxies that capture the overall research quality of conservative analysts as below.

We multiply Accuracy by −1 so that a higher value for the measure indicates a higher level of accuracy.

In untabulated tests, we also examine the last forecast issued by an analyst for a particular stock during a given fiscal year. The “last forecast” subsample is motivated by prior research, which shows that analysts issue relatively more optimistic forecasts and “walk down” the forecasts gradually as they approach the end of the fiscal year (Richardson et al. 2004; Cotter et al. 2006). Overall, the accuracy regression estimates indicate that conservative analysts are less biased and are associated with more accurate earnings forecasts, which is a proxy for overall research quality.

We also use an alternative dependent variable, More Revisions, which takes a value of one when the number of forecasts made by an analyst in a year is in the top 20 %, and re-estimate the specification with the same set of control variables. We find similar results: conservative analysts are 2 % (z-statistic: 1.90) more likely to be in the top 20 % in terms of forecast revisions than other analysts, after controlling for a wide-set of control variables.

The estimates of other variables are also consistent with our expectation and the evidence in the literature. For example, consistent with previous findings (Stickel 1992; Ljungqvist et al. 2007), analysts with higher research quality are more likely to be voted as all-stars. Thus institutional investors are more likely to vote in favor of conservative analysts to reward their superior forecasting.

Although our measure of analyst conservatism differs from that proposed by Hugon and Muslu (2010), our broad findings are consistent.

The contributions to multiple PACs sponsored by the same firm in a given election cycle are aggregated before calculating this ratio. This analysis is limited to brokerage firms that sponsor PACs.

To identify the political preferences of brokerage firms, similar to Hutton et al. (2014), we compute a brokerage-level Republican index, which is defined as the difference between a brokerage firm’s political action committees (PACs) contributions to Republican versus Democratic Senate, House, and Presidential candidates, scaled by the total PAC contributions to candidates of both parties. The CEO-level Republican index is calculated similarly but based on the personal contributions of the CEOs of the brokerage firms.

The definitions of these macroeconomic and sentiment factors are provided in the appendix.

See Levitt (1996) for an additional discussion. In unreported tests, we find that our baseline findings are robust if we focus on the sample of analysts located in the state of New York.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (1998). Ideological realignment in the U.S. electorate. Journal of Politics, 60, 634–652.

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2006). The rise of the ideological voter: The changing bases of partisanship in the American electorate. In J. Green & D. Coffey (Eds.), The State of the Parties: The Changing Role of Contemporary American Parties. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. New York: Henry Holt & Co.

Allport, G. W. (1966). Traits revisited. American Psychologist, 21, 1–10.

Ansolabehere, S., de Figueiredo, J. M., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2003). Why is there so little money in U.S. politics? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17, 105–130.

Atieh, J. M., Brief, A. P., & Vollrath, D. A. (1987). The Protestant work ethic conservatism paradox: Beliefs and values in work and life. Personality and Individual Differences, 8, 577–580.

Bamber, L. S., Jiang, J., & Wang, I. Y. (2010). What’s my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure. The Accounting Review, 85, 1131–1162.

Barber, B. M., Odean, T., & Zhu, N. (2009). Do retail trades move markets? Review of Financial Studies, 22, 151–186.

Barberis, N., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). A model of investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 49, 307–343.

Basu, S. (1997). The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 3–37.

Battalio, R. H., & Mendenhall, R. R. (2005). Earnings expectations, investor trade size, and anomalous returns around earnings announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 77, 289–319.

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2003). Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1169–1208.

Block, J., & Block, J. H. (2006). Nursery school personality and political orientation two decades later. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 734–749.

Bonaparte, Y., Kumar, A., & Page, J. (2012). Political climate, optimism, and investment decisions. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=1509168.

Bonner, S. E., Hugon, A., & Walther, B. (2007). Investor reaction to celebrity analysts: The case of earnings forecast revisions. Journal of Accounting Research, 45, 481–513.

Bonner, S. E., Walther, B. R., & Young, S. M. (2003). Sophistication-related differences in investors’ models of the relative accuracy of analysts’ forecast revisions. The Accounting Review, 78, 679–706.

Brandt, M., Brav, A., Graham, J., & Kumar, A. (2010). The idiosyncratic volatility puzzle: Time trend or speculative episodes? Review of Financial Studies, 23, 863–899.

Brown, L. D., Call, A. C., Clement, M. B., & Sharp, N. Y. (2014). Skin in the game: The inputs and incentives that shape buy-side analysts’ stock recommendations. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=2458544.

Brown, L. D., Call, A. C., Clement, M. B., & Sharp, N. Y. (2015). Inside the “black box” of sell-side financial analysts. Journal of Accounting Research, 53, 1–47.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29, 807–840.

Chen, Q., & Jiang, W. (2006). Analysts’ weighting of private and public information. Review of Financial Studies, 19, 319–355.

Chevalier, J., & Ellison, G. (1999). Are some mutual fund managers better than others? cross-sectional patterns in behavior and performance. Journal of Finance, 54, 875–899.

Christensen, D. M., Dhaliwal, D. S., Boivie, S., & Graffin, S. D. (2014a). Top management conservatism and corporate risk strategies: Evidence from managers’ personal political orientation and corporate tax avoidance. Strategic Management Journal,. doi:10.1002/smj.2313.

Christensen, D. M., Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R., & Wellman L. (2014). From K street to Wall Street: Politically connected analysts and stock recommendations. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=2402411.

Clarke, J., Ferris, S. P., Jayaraman, N., & Lee, J. (2006). Are analyst recommendations biased? Evidence from corporate bankruptcies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41, 169–196.

Clement, M. B. (1999). Analyst forecast accuracy: Do ability, resources, and portfolio complexity matter? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 27, 285–303.

Clement, M. B., & Law K. K. F. (2015). Labor market dynamics and analyst abilities. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=2307253.

Clement, M. B., & Tse, S. Y. (2003). Do investors respond to analysts’ forecast revisions as if forecast accuracy is all that matters? The Accounting Review, 78, 227–249.

Clement, M. B., & Tse, S. Y. (2005). Financial analyst characteristics and herding behavior in forecasting. Journal of Finance, 60, 307–341.

Costantini, E., & Craik, K. H. (1980). Personality and politicians: California party leaders, 1960–1976. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 641–661.

Cotter, J., Tuna, A. I., & Wysocki, P. D. (2006). Expectations management and beatable targets: How do analysts react to explicit earnings guidance? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23, 593–624.

Dechow, P. M., Hutton, A. P., & Sloan, R. G. (2000). The relation between analysts’ forecasts of long-term earnings growth and stock price performance following equity offerings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 17, 1–32.

DeVault, L., & Sias, R. (2014). Hedge fund politics and portfolios. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=2539807.

Easterwood, J. C., & Nutt, S. R. (1999). Inefficiency in analysts’ earnings forecasts: Systematic misreaction or systematic optimism? Journal of Finance, 54, 1777–1797.

Edwards, W. (1968). Conservatism in human information processing. In Benjamin Kleinmuntz (Ed.), Formal representation of human judgment. New York: Wiley.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–193.

Fama, E. F., & MacBeth, J. (1973). Risk, return and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 607–636.

Feather, N. T. (1979). Value correlates of conservatism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1617–1630.

Ge, W., Matsumoto, D., & Zhang, J. L. (2011). Do CFOs have style? An empirical investigation of the effect of individual CFOs on accounting practices. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28, 1141–1179.

Gillies, J., & Campbell, S. (1985). Conservatism and poetry preferences. British Journal of Social Psychology, 24, 223–227.

Gilson, S. C., Healy, P. M., Noe, C. F., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Analyst specialization and conglomerate stock breakups. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 565–582.

Glasgow, M. R., & Cartier, A. M. (1985). Conservatism, sensation-seeking, and music preferences. Personality and Individual Difference, 6, 393–395.

Gleason, C. A., & Lee, C. M. C. (2003). Analyst forecast revisions and market price discovery. The Accounting Review, 78, 193–225.

Goren, P. (1997). Gut-level emotions and the presidential vote. American Politics Research, 25, 203–229.

Graham, J. R., Li, S., & Qiu, J. (2012). Managerial attributes and executive compensation. Review of Financial Studies, 25, 144–186.

Greene, W. (2002). The bias of the fixed effects estimator in nonlinear models. Working paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1292651.

Groysberg, B., Healy, P. M., & Maber, D. A. (2011). What drives sell-side analyst compensation at high-status investment banks? Journal of Accounting Research, 49, 969–1000.

Han, B., & Kumar, A. (2013). Speculative retail trading and asset prices. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 48, 377–404.

Hilary, G., & Menzly, L. (2006). Does past success lead analysts to become overconfident? Management Science, 52, 489–500.

Hirshleifer, D. A., Myers, J. N., Myers, L. A., & Teoh, S. H. (2008). Do individual investors cause post-earnings announcement drift? Direct evidence from personal trades. The Accounting Review, 83, 1521–1550.

Hong, H., & Kacperczyk, M. (2009). The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 15–36.

Hong, H., & Kostovetsky, L. (2012). Red and blue investing: Values and finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 103, 1–19.

Hong, H., & Kubik, J. D. (2003). Analyzing the analysts: Career concerns and biased earnings forecasts. Journal of Finance, 58, 313–351.

Hong, H., Kubik, J. D., & Solomon, A. (2000). Security analysts’ career concerns and herding of earnings forecasts. RAND Journal of Economics, 31, 121–144.

Hsu, C., & Hilary, G. (2013). Analyst forecast consistency. Journal of Finance, 68, 271–297.

Hugon, A., & Muslu, V. (2010). Market demand for conservative analysts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 42–57.

Hutton, I., Jiang, D., & Kumar, A. (2014). Corporate policies of Republican managers. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 49, 1279–1310.

Hutton, I., Jiang, D., & Kumar A. (2015). Political values, culture, and corporate litigation. Management Science, forthcoming.

Hvidkjaer, S. (2008). Small trades and the cross-section of stock returns. Review of Financial Studies, 21, 1123–1151.

Jacob, J., Lys, T. Z., & Neale, M. A. (1999). Expertise in forecasting performance of security analysts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 28, 51–82.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Jost, J. T., & Thompson, E. P. (2000). Group-based dominance and opposition to equality as independent predictors of self-esteem, ethnocentrism, and social policy attitudes among African Americans and European Americans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 209–232.

Kaustia, M., & Torstila, S. (2011). Stock market aversion? Political preferences and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 100, 98–112.

Kini, O., Mian, S., Rebello, M., & Venkateswaran, A. (2009). On the structure of analyst research portfolios and forecast accuracy. Journal of Accounting Research, 47, 867–909.

Kish, G. B. (1973). Stimulus-seeking and conservatism. London: Academic Press.

Kumar, A. (2010). Self-selection and the forecasting abilities of female equity analysts. Journal of Accounting Research, 48, 393–435.

Kumar, A., Niessen-Ruenzi, A., & Spalt, O. G. (2015). What’s in a name? Mutual fund flows when managers have foreign-sounding names. Review of Financial Studies, 28, 2281–2321.

Law, K. K. F., & Mills, L. F. (2015). CEO characteristics and corporate taxes. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2302329.

Lee, J., Lee, K. J., & Nagarajan, N. J. (2014). Birds of a feather: Value implications of political alignment between top management and directors. Journal of Financial Economics, 112, 232–250.

Lee, C. M. C., & Radhakrishna, B. (2000). Inferring investor behavior: Evidence from TORQ data. Journal of Financial Markets, 3, 83–111.

Levitt, S. D. (1996). How do senators vote? Disentangling the role of voter preferences, party affiliation, and senator ideology. American Economic Review, 86, 425–441.

Lin, H. W., & McNichols, M. F. (1998). Underwriting relationships, analysts earnings forecasts and investment recommendations. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25, 101–127.

Livnat, J., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Information interpretation or information discovery: Which role of analysts do investors value more? Review of Accounting Studies, 17, 612–641.

Ljungqvist, A., Marston, F., Starks, L. T., Wei, K. D., & Hong, Y. (2007). Conflicts of interest in sell-side research and the moderating role of institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 85, 420–456.

Malmendier, U., & Shanthikumar, D. M. (2007). Are small investors naive about incentives? Journal of Financial Economics, 85, 457–489.

Malmendier, U., & Shanthikumar, D. M. (2014). Do security analysts speak in two tongues? Review of Financial Studies, 27, 1287–1322.

Martell, R. F., Lane, D. M., & Emrich, C. (1996). Male-female differences: A computer simulation. American Psychologist, 51, 157–158.

McAllister, P., & Anderson, A. (1991). Conservatism and the comprehension of implausible texts. European Journal of Social Psychology, 21, 147–164.

Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R., & Willis, R. H. (1997). Do security analysts improve their performance with experience? Journal of Accounting Research, 35, 131–157.

Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R., & Willis, R. H. (2003). The effect of experience on security analyst underreaction. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 35, 101–116.

Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R., & Willis, R. H. (2007). When security analysts talk, who listens? The Accounting Review, 82, 1227–1253.

O’Brien, P. C. (1988). Analysts forecasts as earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 10, 53–83.

Park, C. W., & Stice, E. K. (2000). Analyst forecasting ability and the stock price reaction to forecast revisions. Review of Accounting Studies, 5, 259–272.

Peterson, B. E., & Lane, M. D. (2001). Implications of authoritarianism for young adulthood: Longitudinal analysis of college experiences and future goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 678–690.

Richardson, S., Teoh, S. H., & Wysocki, P. D. (2004). The walk-down to beatable analyst forecasts: The role of equity issuance and insider trading incentives. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21, 885–924.

Statman, M., & Glushkov, D. (2009). The wages of social responsibility. Financial Analysts Journal, 65, 33–46.

Stickel, S. E. (1992). Reputation and performance among security analysts. Journal of Finance, 47, 1811–1836.

Teoh, S. H., & Wong, T. J. (2002). Why new issues and high-accrual firms underperform: The role of analysts’ credulity. Review of Financial Studies, 15, 869–900.

Walther, B. R., & Willis, R. H. (2013). Do investor expectations affect sell-side analysts’ forecast bias and forecast accuracy? Review of Accounting Studies, 18, 207–227.

Weisbach, M. S. (1995). CEO turnover and the firm’s investment decisions. Journal of Financial Economics, 37, 159–188.

Wilson, G. D. (1973). A dynamic theory of conservatism. In G. D. Wilson (Ed.), The psychology of conservatism. London: Academic Press.

Zitzewitz, E. (2001). Measuring herding and exaggeration by equity analysts and other opinion sellers. Working paper, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/abstract_id=405441.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Sloan (the Editor), an anonymous referee, Vikas Agarwal, Anup Agrawal, Ray Ball, Brian Boyer, Tim Burch, Vidhi Chhaochharia, Ilia Dichev, Harrison Hong, Artur Hugon, George Korniotis, Andy Leone, Sonya Lim, Volkan Muslu, Dhananjay Nanda, Devin Shanthikumar, and seminar participants at University of Alabama, University of Miami, and Florida Atlantic University for helpful discussions and valuable comments. We also thank Hope Han, Kyu Kim, Taeyoung Kim, and Ryan Rhee for dedicated research assistance. We are responsible for all remaining errors and omissions. Previous versions of the paper were circulated under the title “Republican Equity Analysts.”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: Variable Definitions

Appendix: Variable Definitions

The following data sources are used to construct our variables: American Religion Data Archive (ARDA), Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB), Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Center for Research on Security Prices (CRSP), Compustat, Federal Election Commission (FEC), Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System from Thomson Reuters (IBES), Institutional Investor Magazine (II), Nelson’s Directory of Investment Research (Nelson), Thomson Reuters 13f institutional ownership dataset (13f), Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers (UMich), Thomson Reuters’ Securities Data Company dataset (SDC), Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), ISSM/TAQ, and various Internet Sources for hand collected data.

Key independent variables | Source |

|---|---|

PolCons: An indicator variable that takes the value of one if all political contributions of an analyst during the sample period are made to the Republican Party. | FEC, IBES |

PolConsRatio: Political contributions to the Republican Party of an analyst divided by all of her political contributions to both the Democratic and Republican Parties during the sample period. We use this ratio to define conservative analysts based on a majority of the contributions made to the Republican Party. | FEC, IBES |

Three-way politically conservative indicator: An indicator that takes +1 for analysts who donate only to Republicans, −1 for analysts who donate only to Democrats and 0 for other analysts. | FEC, IBES |

Dependent variables | Source |

|---|---|

All-star: An indicator that takes the value of one if an analyst is ranked as either first, second, third, or runner-up in the October issue of the Institutional Investor magazine. | II, IBES |

Bold forecast: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when the forecast is either above both the prevailing consensus and an analyst’s own most recent forecast or below both of those benchmarks. | CRSP, IBES |

Demote: An indicator that takes the value of one when an analyst moves to a smaller brokerage in next year conditional on the analyst remaining in IBES in the following year. | IBES |

Media: The number of news articles in the Factiva database that mention the name of an analyst in a given year. | Factiva |

More accurate: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when the accuracy of all earnings forecasts made by an analyst in a year is ranked in the top 20 percent. | CRSP, IBES |

Number of revisions: The natural logarithm of the number of revisions made by an analyst in a year. | IBES |

Promote: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when an analyst moves to a larger brokerage in the next year conditional on the analyst remaining in IBES in the following year. | IBES |

Small change in earnings forecast: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when the absolute change in the earnings forecast made by an analyst is smaller than the average absolute changes in earnings forecasts made by all other analysts covering the same stock in the prior 12 months within the same fiscal year. | CRSP, IBES |

Small stock recommendation change: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when the revision in recommendation rating for a given firm is to its immediately adjacent rating category. | IBES |

Size-adjusted cumulative abnormal return (CAR): Buy-and-hold return of the firm minus the buy-and-hold return for an equal-weighted portfolio of firms in the same NYSE size decile formed at the beginning of each year. | CRSP, IBES |

Terminate An indicator variable that takes the value of one when an analyst ceases to appear in IBES in the following year. | IBES |

Independent variables | Source |

|---|---|

Accuracy: Negative value of the absolute difference between an analyst’s one-year-ahead earnings forecast and the actual earnings (i.e., Forecast EPS – Actual EPS) divided by the share price two trading days before the forecast announcement date. | CRSP, IBES |

Affiliated: An indicator variable that takes the value of one if an analyst works at a brokerage that is either a lead underwriter or a co-underwriter of an initial public offering of the covered stock during the past five years or a secondary equity offering during the past two years. | IBES, SDC |

Book-to-market equity: Ratio of book equity to market equity for the firm being covered, where book equity is the sum of total assets, deferred taxes, and convertible debt minus total liabilities and preferred stock, and market equity is the product of share price and common shares outstanding. Both book equity and market equity are measured as of the most recent December. | Compustat, CRSP |

Brokerage size: Natural logarithm of the number of analysts in a brokerage in the year. | IBES |

Days since last forecast: Natural logarithm of one plus the number of days since the most recent forecast issued by an analyst following the firm. | IBES |

Firm size: Natural logarithm of market capitalization (in thousands) of a firm at the end of the prior month. | CRSP |

Firm-specific experience: Natural logarithm of one plus the number of years an analyst has covered the firm. | IBES |

Forecast frequency: Natural logarithm of one plus the number of earnings forecasts issued by an analyst in a year. | IBES |

Forecast horizon: Natural logarithm of one plus the number of days to the fiscal year-end for an earnings forecast. | IBES |

General experience: Natural logarithm of one plus the number of years since an analyst first appears in IBES. | IBES |

Institutional ownership: Fraction of shares held by institutional managers reported in the latest quarter-end 13f filings divided by the number of shares outstanding for the firm being covered. | 13f |

Lagged accuracy: Negative value of the absolute difference between an analyst’s one-year-ahead earnings forecast and the actual earnings (i.e., Forecast EPS-Actual EPS) divided by the share price two trading days before the forecast announcement date by an analyst in prior fiscal year. | CRSP, IBES |

Local religiosity: The total number of church adherents over the total population in the county where the analyst resides. | ARDA, Nelson |

Momentum: Cumulative return in the past 12 months ending in the prior month. | CRSP |

Number of analysts: Number of analysts following the firm in a year. | IBES |

Number of companies: Number of companies followed by an analyst in a year. | IBES |

Number of forecasts: Number of forecasts made by an analyst in a year. | IBES |

Number of industries: Number of industries based on the two-digit SICs followed by an analyst in a year. | IBES |

Reco revision signal: An indicator variable that takes the value of one when an analyst upgrades the recommendation for the firm, the value of −1 when an analyst downgrades the recommendation, and zero when there is no change in recommendation. | IBES |

Revision magnitude: Difference between an analyst’s current and previous forecasts for a given firm, divided by the share price two days before the forecast announcement date. | CRSP, IBES |

Revision signal: It takes the value of one when an analyst’s new forecast is above both her own prior forecast and the prior consensus for the firm, −1 when the forecast is below both her own prior forecast and the prior consensus, and zero otherwise. | CRSP, IBES |

Retail trading proportion: The ratio of the total monthly buy-and-sell-initiated small trades (trade size below $5,000 in 1991 dollar value) dollar volume and the total stock trading dollar volume in the same month. | ISSM/TAQ |

WW fundamental: A set of quarterly measures of macro-economic conditions following Walther and Willis (2012), including (1) real GDP growth, (2) consumption growth, (3) unemployment rate, (4) default spread, (5) term spread, (6) yield on the three-month U.S. Treasury bill, (7) change in the consumer price index, and (8) dividend yield on the CRSP value-weighted index. | FRED |

WW sentiment: The residuals from regressions of quarterly index of consumer sentiment on the seven quarterly measures of macro-economic conditions (WW Fundamental). | BEA, BLS, CRSP, UMich, FRB |

Other variables | Source |

|---|---|

Age: Age of an analyst, hand collected. | Various Internet Sources |

Foreign sounding name: An indicator variable that takes the value of one for an analyst when at least 75 % of the Amazon’s Mechanical Turk workers we hired indicated so. For details of variable construction, please refer to Kumar, Niessen-Ruenzi, and Spalt (2015). | Various Internet Sources |

Male: An indicator variable that takes the value of one for male analysts and zero for female analysts. Hand collected and only available for a very small number of analysts in the sample. | Various Internet Sources |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, D., Kumar, A. & Law, K.K.F. Political contributions and analyst behavior. Rev Account Stud 21, 37–88 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9344-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-015-9344-9