Abstract

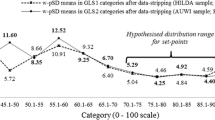

Understanding subjective wellbeing (SWB) at the population level has major implications for governments and policy makers concerned with enhancing the life quality of citizens. The Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) is a measure of SWB with theoretical and empirical credentials. Homeostasis theory offers an explanation for the nature of SWB data, including the distribution of scores, maintenance and change over time. According to this theory, under normal conditions, the dominant constituent of SWB is Homeostatically Protected Mood (HPMood), which is held within a genetically determined range of values around a set-point. However, in extreme circumstances (e.g., financial hardship, chronic illness), HPMood may dissociate from SWB, as cognitive/emotional reactions to the cause of homeostatic challenge assume control over SWB. This study investigates two groups as people scoring in the positive range for SWB and people who are likely to be experiencing homeostatic defeat/challenge. We test whether the reduced influence of HPMood on SWB due to homeostatic defeat has implications for the validity of SWB measurement. Participants were 45,192 adults (52 % female), with a mean age of 48.88 years (SD = 17.35 years), who participated in the first 23 surveys of the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index over the years 2001–2010. Multiple regression analysis, multiple group confirmatory factor analysis, and Rasch modelling techniques were used to evaluate the psychometric performance of the PWI across the two groups. Results show that while the PWI functioned as intended for the normal group, SWB in the challenged group was lower across all PWI domains, more variable, and the domain scores lacked the strength of inter-correlation observed in the normal, comparison group. These changes are consistent with predictions based on homeostasis theory and one major implication of the findings is that SWB measures may not function equivalently across the entire spectrum of possible domain satisfaction scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A reviewer pointed out that the large sample size discrepancy between the positive (n = 43,534) and defeated group (n = 1,658) might undermine between group comparisons. To test whether variance restriction was an issue in the defeated group we took random sub-samples of various sizes and plotted the variation to see at which point it stabilized within that group. Even when the random subsample size was 10 % (i.e., n = 166), the range of variance was stable (standard deviation only varied by around 1) across random subsamples suggesting that increasing that sample size would have little effect on range of scores and variance in that group. Furthermore, as the sample size increased, the variation in standard deviations was small and seemingly random.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: Americans’ perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum Press.

Andrich, D., Sheridan, B., & Luo, G. (2010). RUMM 2030. 4.0 for windows (upgrade 4600.0109) edn. Perth, WA: RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd.

Blore, J. D., Stokes, M. A., Mellor, D., Firth, L., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). Comparing multiple discrepancies theory to affective models of subjective wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 100, 1–16. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9599-2.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group, LLC.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources.

IBM Corp (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Cummins, R. A. (1995). On the trail of the gold standard for subjective wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 35, 179–200. doi:10.1007/BF01079026.

Cummins, R. A. (1998). The second approximation to an international standard for life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 43(3), 307–334. doi:10.1023/a:1006831107052.

Cummins, R. A. (2000). Objective and subjective quality of life: An interactive model. Social Indicators Research, 52, 55–72. doi:10.2307/27522495.

Cummins, R. A. (2010). Subjective wellbeing, homeostatically protected mood and depression: A synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9167-0.

Cummins, R. A., & Nistico, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 37–69. doi:10.1023/a:1015678915305.

Cummins, R., & Wooden, M. (2014). Personal resilience in times of crisis: The implications of SWB homeostasis and set-points. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 223–235. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9481-4

Cummins, R. A., Woerner, J., Weinberg, M., Collard, J., Hartley-Clark, L., Perera, C., & Horfiniak, K. (2012). Australian unity wellbeing index-report 28-the wellbeing of Australians-the impact of marriage. Retrieved 26 April 2014. http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/reports/survey-reports/index.php.

Cummins, R. A., Li, L., Wooden, M., & Stokes, M. (2014). A demonstration of set-points for subjective wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 183–206. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9444-9.

Curran, P. J., West, G. W., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1, 16–29.

Davern, M., Cummins, R. A., & Stokes, M. (2007). Subjective wellbeing as an affective-cognitive construct. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 429–449. doi:10.1007/s10902-007-9066-1.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective wellbeing. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7, 181–185.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Forjaz, M. J., Ayala, A., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Prieto-Flores, M.-E., Fernandez-Mayoralas, G., Rojo-Perez, F., et al. (2012). Rasch analysis of the international wellbeing index in older adults. International Psychogeriatrics, 24, 324–332.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hartley, H. O. (1950). The use of range in analysis of variance. Biometrika, 37, 271–280.

Headey, B., Holmstrom, E., & Wearing, A. (1984a). The impact of life events and changes in domain satisfactions on well-being. Social Indicators Research, 15, 203–227. doi:10.1007/bf00668671.

Headey, B., Holmstrom, E., & Wearing, A. J. (1984b). Well-being and ill-being: Different dimensions? Social Indicators Research, 14, 115–139. doi:10.1007/bf00293406.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1989). Personality, life events, and subjective wellbeing: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 731–739. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.731.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1992). Understanding happiness: A theory of subjective wellbeing. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Helson, H. (1964). Adaptation-level theory. New York: Harper & Row.

Hu, L. Ä., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

International Wellbeing Group. (2006). Personal Wellbeing Index-Adult (PWI-A).

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3), 186–189.

Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2011). Mplus User's Guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Educational Research.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2000). A first course in structural equation modeling. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence A Erlbaum Associates.

Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 1, 145.

Steel, P., & Ones, D. S. (2002). Personality and happiness: A national level analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 767–781.

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). Subjective wellbeing and homeostatically protected mood: Theory validation with adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 897–914. doi:10.1007/s10902-010-9235-5.

Veenhoven, R. (1994). Is happiness a trait’? Test of the theory that a better society does not make people any happier. Social Indicators Research, 32, 101–160.

Vitterso, J. (2001). Personality traits and subjective wellbeing: Emotional stability, not extraversion, is probably the important predictor. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 903–914.

Vitterso, J., & Nilsen, F. (2002). The conceptual and relational structure of subjective wellbeing, neuroticism, and extraversion: Once again, neuroticism is the important predictor of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 57, 89–118.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richardson, B., Fuller Tyszkiewicz, M.D., Tomyn, A.J. et al. The Psychometric Equivalence of the Personal Wellbeing Index for Normally Functioning and Homeostatically Defeated Australian Adults. J Happiness Stud 17, 627–641 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9613-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9613-0