Abstract

One of the most cited papers in Applied Mechanics is the work of Eshelby from 1957 who showed that a homogeneous isotropic ellipsoidal inhomogeneity embedded in an unbounded (in all directions) homogeneous isotropic host would feel uniform strains and stresses when uniform strains or tractions are applied in the far-field. Of specific importance is the uniformity of Eshelby’s tensor \(\mathbf{S}\). Following Eshelby’s seminal work, a vast literature has been generated using and developing Eshelby’s result and ideas, leading to some beautiful mathematics and extremely useful results in a wide range of application areas. In 1961 Eshelby conjectured that for anisotropic materials only ellipsoidal inhomogeneities would lead to such uniform interior fields. Although much progress has been made since then, the quest to prove this conjecture is still not complete; numerous important problems remain open. Following a different approach to that considered by Eshelby, a closely related tensor \(\mathbf{P}=\mathbf{S}\mathbf{D}^{0}\) arises, where \(\mathbf{D}^{0}\) is the host medium compliance tensor. The tensor \(\mathbf{P}\) is associated with Hill and is of course also uniform when ellipsoidal inhomogeneities are embedded in a homogeneous host phase. Two of the most fundamental and useful areas of applications of these tensors are in Newtonian potential problems such as heat conduction, electrostatics, etc. and in the vector problems of elastostatics. Knowledge of the Hill and Eshelby tensors permit a number of interesting aspects to be studied associated with inhomogeneity problems and more generally for inhomogeneous media. Micromechanical methods established mainly over the last half-century have enabled bounds on and predictions of the effective properties of composite media. In many cases such predictions can be explicitly written down in terms of the Hill tensor, or equivalently the Eshelby tensor and can be shown to provide excellent predictions in many cases.

Of specific interest is that a number of important limits of the ellipsoidal inhomogeneity can be taken in order to be employed in predictions of the effective properties of, for example, layered media and fibre reinforced composites and also to the cases when voids and cracks are present. In the main, results for the Hill and Eshelby tensors are distributed over a wide range of articles and books, using different notation and terminology and so it is often difficult to extract the necessary information for the tensor that one requires. The case of an anisotropic host phase is also frequently non-trivial due to the requirement of the associated Green’s tensor. Here this classical problem is revisited and a large number of results for problems that are felt to be of great utility in a wide range of disciplines are derived or recalled. A scaling argument leads to the derivation of the Eshelby tensor for potential problems where the host phase is at most orthotropic, without the requirement of using the anisotropic Green’s function. The Concentration tensor \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}\) linking interior fields to those imposed in the far-field is derived for a wide variety of problems. These results can therefore be used in the various micromechanical schemes.

Directly related to the tensors of Eshelby and Hill is the so-called Moment tensor \(\mathbf{M}\). As well as arising in the literature on micromechanics, this tensor is important in the vast area of research associated with inverse problems and specifically with the problem of identifying an object inside some domain given the application of a specific set of boundary conditions. Due to its fundamental importance and direct link to the Eshelby and Hill tensors, here we state the connection between \(\mathbf{M}, \mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\) in an effort to ensure that the work is of use to as wide a community as possible.

Both tensor and matrix formulations are considered and contrasted throughout. Appendices give various details that illustrate the implementation of both approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The canonical isolated inhomogeneity problem has been of fundamental importance in a number of materials modelling problems now for well over a century. This problem is the following: a single inhomogeneity or particle of general shape, with different material properties to that of the surrounding material is embedded inside an unbounded (in all directions, i.e., free-space) homogeneous host medium. Given some prescribed conditions in the far-field, what form do the fields take within the inhomogeneity? As well as being interesting in its own right, this problem is of utmost importance in homogenization, micromechanics and multiscale modelling.

The first to consider this kind of inhomogeneity problem was Poisson in 1826 [103] who studied the perturbed field due to an isolated ellipsoid in the context of the Newtonian potential problem. He showed that given a uniform electric polarization (or magnetization), the induced electric (or magnetic) field inside the ellipsoid is also uniform. In 1873 Maxwell [83] derived explicit expressions for this field. Early work in linear elasticity saw a number of studies determine the field inside and around inhomogeneities, including the important case of a cavity (since this was correctly recognized as a defect or flaw). Examples of these works are those associated with the case of spheres [43, 118], spheroids [29] and ellipsoids [107, 113, 114] but all considered specific loadings, usually of the homogeneous type in the far-field, meaning uniform tractions or displacements that are linear in the independent Cartesian variable, say \(\mathbf{x}\).

The inhomogeneity problem is now usually associated with the name of Eshelby because in 1957 he showed that for general homogeneous conditions imposed in the far-field, the strain set up inside an isotropic homogeneous ellipsoid is uniform [31]. In 1961 Eshelby [32] conjectured that “…amongst closed surfaces, the ellipsoid alone has this convenient property…”. One could ask is this really true? In the sense of what it is thought that Eshelby meant when he made this conjecture (the so-called weak Eshelby conjecture, where the interior field must be uniform for any homogeneous far-field loading), this statement certainly is true although this was only proved in 2008, simultaneously by Kang and Milton [56] and Liu [71] in the case of isotropic media. There is a slightly different version (the so-called strong Eshelby conjecture), where the interior field must be uniform only for a specific, single uniform far-field loading. This strong conjecture has not been proven in the context of three dimensional isotropic linear elasticity, although significant progress has been made in the last decade, see [55] for a review. The results obtained in [4] go beyond the weak Eshelby conjecture but still do not fully prove the strong conjecture. Interestingly the weak conjecture for the associated Newtonian potential problem was proved some time before Eshelby’s 1957 elastostatics paper, by Dive in 1931 [24] and Nikliborc [97] in 1932, see also the discussion in [55, 56, 71]. In deriving these results, Dive and Nikliborc proved the converse of Newton’s theorem that if \(V_{1}\) is an ellipsoid of uniform density, the gravitational force in \(V_{1}\) is zero [58]. The strong conjecture in the context of the potential problem is true in two dimensions [111, 115] but is not true in dimensions greater than two: a non-ellipsoidal counterexample associated with a specific far-field loading (equivalently a specific eigenstress) was found by Liu [71].

It is important to note that the proofs of Eshelby’s conjectures in elastostatics referred to above correspond to simply connected, isotropic inhomogeneities with Lipschitz boundaries. Eshelby’s work was followed up by numerous researchers who considered the general anisotropic case [6, 8, 32, 61, 70, 121, 122, 129, 133]. In 1974 Cherepanov [22] proved that multiple inhomogeneities of non-ellipsoidal shape can interact in order to render the interior fields uniform; see also Kang and Milton [56] and Liu [71] who coined the term E-inclusions for such interacting inhomogeneities. Liu and co-workers have also considered the periodic Eshelby problem in two dimensions [72, 73]. Kang and Milton [56] used their approach to prove Eshelby’s weak conjecture in the context of the fully anisotropic potential problem. Most notably however, it is stressed again that the weak Eshelby conjecture for elasticity has not yet been proved in the context of anisotropic elasticity.

Interest in deriving the Eshelby tensor for non-ellipsoidal inhomogeneities has always been active in order to show that the conjecture holds for specific classes of inhomogeneities. Particular attention has been paid to polygonal and polyhedral inhomogeneities and the associated properties of Eshelby’s tensor [57, 74, 79, 80, 93, 94, 98, 108]. The supersphere case has been considered recently by [18] building on the work by [99, 100, 119]. A general method was developed by Ru [110] in order to obtain an analytical solution associated with a two dimensional inhomogeneity of arbitrary cross section and explicit forms of the stress inside hypotrochoidal and rectangular inhomogeneities were derived. Some analytical expressions have recently been derived for two-dimensional problems in the Newtonian potential and plane elastostatics problems where inhomogeneities are either polygonal or their shape can be described by finite Laurent expansions [140, 141]. Additional useful properties of the Eshelby tensor have been deduced, including the relationship of the averaged Eshelby tensor for non-ellipsoidal inhomogeneities to their ellipsoidal counterparts [126, 137].

More recently the inhomogeneity problem has been studied in the nonlinear elasticity context where results associated with Eshelby’s conjecture have been proved in two dimensions for so-called harmonic materials [59, 60, 112]. Although nonlinear problems are generally more difficult than linear elastostatics, the nonlinearity frees up a number of issues that are more constrained in linear problems. The study of nonlinear problems with dilatational eigenstrain was recently carried out in [135]. Giordano [41] considered the nonlinearly elastic inhomogeneity problem but where the constitutive behaviour is described via expansions in strain (Landau elasticity).

Here, due to the associated vast theoretical and practical interest, attention is restricted to the case of linear problems for ellipsoidal inhomogeneities and associated limits in the context of the Newtonian potential problem and elastostatics. A general approach to deriving the Hill tensor \(\mathbf{P}\) and proving many of its properties is to use the integral equation form of the governing equations [132]. In fact Eshelby approached the problem in quite a different manner, using the concept of eigenstrain [31]. Hill [47] considered the so-called polarization (hence P) of an ellipsoid. The review articles of Walpole [123] and Willis [132], who developed the integral form of the Hill tensor, have been very influential and the text of Mura [92] describes the associated Green’s tensor and form of the Eshelby tensor \(\mathbf{S}\) for elastostatics in detail. The consideration of isolated inhomogeneity problems allows the derivation of the so-called concentration tensor \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}\), of use in dilute micromechanical schemes, where interactions between inhomogeneities are not important [134]. This tensor is related to the Hill tensor via the expression

where \(\mathbf{C}^{0}\) and \(\mathbf{C}^{1}\) are the modulus tensors of the host and inhomogeneity respectively and \(\mathbf{I}\) is the identity tensor. In the field of micromechanics a number of very ingenious approximations have been made that lead to rather excellent predictions of effective properties in the case where interactions amongst inhomogeneities are important (see [81, 127, 132] for broad overviews). Finally it is noted that variational bounds can be conveniently written down in terms of the Hill or Eshelby tensors [17, 45, 102, 105, 128, 130, 132], with those of the Hashin-Shtrikman type being particularly important.

There is no real preference for the direct integral equation approach leading to the Hill tensor, over the Eshelby eigenstrain approach. It is chiefly down to individual preference although it is important to note that Hill’s tensor possesses the major symmetries whereas Eshelby’s does not in general. Some find the notion of eigenstrain rather artificial, although in many cases it is a very useful concept as a means for solving harder problems such as determining fields inside multiple inhomogeneities [91, 138]. The simple relation

between the Hill and Eshelby tensors, means that deriving one immediately yields the other.

The Hill and Eshelby tensors are of great utility in a number of micromechanical methods and what is quite astonishing is that they can be evaluated analytically in a large number of very important cases. However, results are distributed over a large number of articles, reviews and textbooks, and furthermore often in articles that span a wide range of scientific fields due to the wide ranging applicability of the theory. References dealing with derivations of specific results are those of [10, 14, 28, 81, 106, 123, 132] and [67]. The field is still very much alive, pushed forward by both unresolved theoretical issues as well as applications involving not only inhomogeneities but also cracks and dislocations [95, 139] and by the desire to fully resolve the open issues described above. Recent work has focused in more detail on inhomogeneities of general shape and how these can feed into models of inhomogeneous media with distributions of non-canonical inhomogeneities [14–16, 33–35, 138, 140, 141]. Such studies are important to understand how local stress fields develop in the medium under loading. This is highly dependent upon the inhomogeneity shape. It must always be stressed that the utility of the Eshelby tensor itself for general shapes in micromechanical methods is limited by the fact that fields interior to the inhomogeneity are not generally uniform in such cases and therefore the tensor does not arise as a natural quantity from the governing integral equations ((2.7) and (2.11) below) as it does in the case of ellipsoidal inhomogeneities.

Another important tensor that arises in inhomogeneity problems and has a direct link to the Eshelby and Hill tensors is the Moment tensor \(\mathbf{M}\). In the case of ellipsoidal inhomogeneities with homogeneous boundary conditions in the far-field, this tensor is most easily written down in terms of the Concentration tensor as

where \(|V_{1}|\) is the volume of the inhomogeneity. For further discussion on the broader nature of the Moment tensor, see the book by Ammari and Kang [1] and also [4]. It plays an important role in the vast area of research associated with inverse problems and specifically with the problem of identifying an object inside some domain given the application of a specific set of boundary conditions. The Moment tensor arises within the conjecture of Pólya-Szegö [104] from 1951 (pre-dating that of Eshelby), which states that the trace of the moment tensor is a minimum for circular (spherical) inhomogeneities in 2(3) dimensions. As should be obvious there are strong connections between this conjecture and the Eshelby conjecture. We refer to [4, 56] for further details.

Here the objective is to gather together important results associated with the Hill and Eshelby tensors for ellipsoidal inhomogeneities in a consistent notation, derive a number of important limiting cases such as those associated with cracks and cavities, derive compact results associated with the anisotropic potential problem and finally derive and state associated Concentration tensors. This should prove useful to many who frequently require the form of the \(\mathbf{P}\)- or \(\mathbf{S}\)-tensors in practice but who struggle to find the appropriate reference. The emphasis here is to derive the Hill, Eshelby and Concentration tensors but as is clear from (1.3) the Moment tensor follows straightforwardly from these.

An important point to note is that using the so-called invariant notation, potential and linear elastostatics problems can be considered simultaneously, only that the latter is a higher order tensor analogue of the former. Here however the applications are made distinct in order to stress the different results and mechanisms for deriving these expressions. In particular the results from potential theory feed into those from linear elastostatics. As a result, index notation shall be used almost entirely throughout.

In much of the literature on micromechanics the terms inclusion and inhomogeneity are used interchangeably. However in some cases they are used to make an important distinction. An inhomogeneity is defined as a particle of general shape having different material properties to those of the surrounding medium in which it is embedded. On the other hand the terminology inclusion is used to represent a general shaped region within some medium that has the same properties as the surrounding medium but where this finite inclusion region has been subject to some eigenstrain (e.g., thermal strain). This differentiation is used, e.g., in Mura [92] and Qu and Cherkaoui [106] and it is also adopted here.

In Sect. 2 the integral equation formulation of the inhomogeneity problem is stated, yielding integral equations for the potential gradient and strain inside an inhomogeneity. In Sect. 3 it is illustrated that such fields are uniform when the inhomogeneity is ellipsoidal and the general expressions for the associated Hill tensors are stated. The notion of Concentration tensors is also discussed. In Sects. 4 and 5 specific results are then stated and derived for the cases of the Newtonian potential problem and elastostatics respectively. A closing discussion is given in Sect. 6 describing how the results are used in micromechanical methods together with a summary of current areas of associated research. Numerous important details and results are stated in Appendices in order for this review to be comprehensive but also to aid the flow of reading, in particular the mechanism for representing tensors of certain symmetries with respect to appropriate tensor bases, tensor contractions, and the matrix formulation of operations between tensors are covered in Appendix C.

As many pertinent references are given as possible; it is important to stress that the focus is specifically on the formulation of the Eshelby, Hill and Concentration tensors rather than articles associated with micromechanical methods, of which there are thousands. For the latter the interested reader is referred to the many textbooks that have been written over the last decade, e.g., [14, 28, 54, 67, 106].

2 Integral Equation Formulation

Index notation shall be used for tensors throughout, working in Cartesian coordinates and using repeated subscripts to imply summation. The term unbounded will be used when referring to free-space, i.e., unbounded in all directions. Although a general invariant formulation can be employed to deal with problems in the potential and linear elastostatics context simultaneously [132], this approach can obfuscate details that are important when it comes to deriving specific Hill and Eshelby tensors for given anisotropies and inhomogeneity shapes, which is the main purpose of this article.

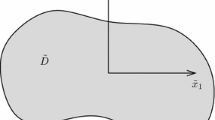

Notation is as defined in Fig. 1 for both the potential problem and linear elastostatics. A single isolated inhomogeneity \(V_{1}\), for the time being of general shape and with surface \(\partial V_{1}\) is embedded (perfectly) inside an unbounded homogeneous medium \(V\) and the medium exterior to \(V_{1}\) is denoted as \(V\backslash V_{1}=V_{0}\). Both materials are considered generally anisotropic so that their material modulus tensors are

in the context of the potential problem and

in the context of elastostatics. Here the so-called characteristic function associated with a domain \(V_{1}\), has been employed, being defined as

Finally it is noted that the inhomogeneity (\(C_{ij}^{1}\) and \(C^{1}_{ijk\ell }\)) and host (\(C_{ij}^{0}\) and \(C^{0}_{ijk\ell}\)) modulus tensors are uniform tensors, meaning that each component of the tensor is constant but these constants can be different.

2.1 The Potential Problem

Since it is often useful to consider a specific physical problem, certainly in terms of language and terminology, the potential problem is described in the context of steady state thermal conductivity. The equation governing the steady state temperature distribution \(T(\mathbf {x})\) in the medium described above and depicted in Fig. 1 is

where the assumption is that no heat sources are present. The free-space Green’s function associated with the host phase satisfies

as well as the far-field condition \(\lim_{\mathbf{x}\rightarrow \infty }G(\mathbf{x})=0\). Assuming continuity of temperature and normal flux across \(\partial V_{1}\), the resulting temperature distribution may be straightforwardly derived in integral equation form as

which holds for all \(\mathbf{y}\). Here \(T^{*}(\mathbf{y})\) is the solution to the equivalent problem satisfying (2.4) with no inhomogeneity present (or equivalently with \(C_{ij}^{1} = C_{ij}^{0}\)). Upon taking derivatives of (2.6) with respect to \(y_{i}\) and noting the property \(\partial G/\partial x_{i}= -\partial G/\partial y_{i}\) it is found that for all \(\mathbf{y}\in V\),

where the \(i\)th component of the temperature gradient has been defined as \(e_{i}=\partial T/\partial x_{i}\).

2.2 Elastostatics

The origins of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor reside in the context of elastostatics rather than in potential problems even though the theory is of course analogous. The \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor originated with Hill [47] who also introduced the compact notation (now commonly referred to as Hill notation) for transversely isotropic fourth order tensors, which is summarized in Appendix C.2.3. Walpole [122], Willis [130–132] and Laws [62] amongst others followed this with influential work associated with inhomogeneities of specific shapes, paying particular attention in many cases to the scenarios of discs, fibres and cracks. A number of \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensors are also stated in the excellent concise review of micromechanics by Markov [81] although unfortunately, some typographical errors are present there and these are corrected here.

The integral equation formulation of the isolated inhomogeneity problem in elastostatics proceeds analogously to the potential problem with an expected increase in complexity. The equations governing the elastic displacement \(\mathbf{u}\) in the medium described above and depicted in Fig. 1 are

where body forces have been neglected. The associated Green’s tensor of the host phase satisfies

as well as the far-field condition \(\lim_{\mathbf{x}\rightarrow \infty }G_{ij}(\mathbf{x})=0\), noting that \(G_{ij}=G_{ji}\). The resulting displacement field in the medium may be straightforwardly derived in integral equation form as

which holds for all \(\mathbf{y}\). Here \(u_{i}^{*}(\mathbf{y})\) is the solution to the equivalent problem satisfying (2.8) with no inhomogeneity present, or equivalently \(C^{1}_{ijk\ell}=C^{0}_{ijk\ell}\). As in the potential problem, take derivatives of both sides of (2.10) to form the strain tensor \(e_{ij}=(\partial u_{i}/\partial x_{j} +\partial u_{j}/\partial x_{i})/2\) and use the property \(\partial G_{ki}/\partial x_{j}= -\partial G_{ki}/\partial y_{j}\) so that, for all \(\mathbf{y}\in V\),

Here the notation \(|_{(k\ell),(ij)}\) indicates symmetry with respect to the pair of indices grouped together inside parentheses, so that upon defining

one can write

3 Uniformity of the Hill and Eshelby Tensors

3.1 The Potential Problem

Impose so-called homogeneous temperature gradient conditions (in the language of micromechanics: such conditions would lead to a homogeneous temperature gradient in a homogeneous medium) so that in the far-field when \(|\mathbf{x}|\rightarrow\infty\),

where \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) is uniform and therefore \(T^{*} = \theta_{i} x_{i}\) and \(e_{i}^{*}=\theta_{i}\). Referring to (2.7), one then asks, is there an inhomogeneity of any shape that can give rise to a uniform temperature gradient field inside the inhomogeneity, i.e., for \(\mathbf{y}\in V_{1}\)? If such an inhomogeneity does exist, then (2.7) is only consistent for \(\mathbf{y}\in V_{1}\) if the tensor defined as

is also uniform, i.e., is independent of \(\mathbf{y}\). The tensor \(\mathbf{P}\) with components \(P_{ij}\) defined in (3.2) is known as Hill’s Polarization tensor for the potential problem and it possesses the symmetry \(P_{ij}=P_{ji}\). If \(\mathbf{P}\) is not uniform, it would mean that the assumption of a uniform temperature gradient field inside the inhomogeneity was incorrect.

It transpires that when the inhomogeneity region is ellipsoidal the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor defined in (3.2) is indeed uniform. This is proved in Appendix A.1, where it is also shown that the general form for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor can be defined in terms of an integral over the surface of the unit sphere \(S^{2}\).

Clearly since the integral is over the surface of the unit sphere \(S^{2}\), it is sensible to resolve \(\overline{\xi}_{i}\) into spherical polar coordinates for the purposes of evaluating this integral. The form of (3.3) illustrates the important general result that the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor is uniform for an arbitrarily anisotropic ellipsoidal inhomogeneity embedded inside an arbitrarily anisotropic host phase. That Eshelby’s (weak) conjecture is true for anisotropic potential problems [56, 71], means that the ellipsoid is the only shaped inhomogeneity for which the interior temperature gradient is uniform under any such far-field condition of the form (3.1). The fact that the strong conjecture is not true in the Newtonian potential problem means that there exists shapes where the interior temperature gradient field can be uniform for specifically chosen homogeneous far-field conditions [71].

To determine the appropriate \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in any circumstance then one can appeal to (3.3) and carry out the necessary integration. Alternatively, as shall be shown in Sect. 4, in many cases it is relatively straightforward to use symmetry arguments and results from potential theory in the isotropic host case together with scalings in some cases of host anisotropy, in order to derive explicit results, often in a more straightforward manner than by directly evaluating the general expression (3.3). In fact in the potential problem context, symmetry arguments and results from potential theory [58] are often sufficient to derive results for many special cases of ellipsoids in host media that are at most orthotropic. The general result (3.3) is thus suitable for more complex anisotropies than orthotropy or for example if the semi-axes of the ellipsoid are not aligned with the axes of symmetry of host anisotropy.

It should be recalled that the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor is independent of the anisotropy of the inhomogeneity and therefore arbitrary anisotropy can be retained for the inhomogeneity domain. The only aspects of the inhomogeneity that influence the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are its shape and, for anisotropic host phases, its orientation with respect to the axes of anisotropy of the host phase. It is important to note the following three points:

-

In the host region \(V_{0}\) the temperature gradient is generally not uniform.

-

For non-homogeneous temperature gradient conditions in the far-field, the temperature gradient field inside an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity is generally not uniform. However if the prescribed temperature gradient is a polynomial of order \(n\), then so is the field inside an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity, see [6]. This is known as the polynomial conservation property for ellipsoids.

-

Generally for non-ellipsoidal inhomogeneities in unbounded domains and general shaped inhomogeneities in bounded host domains \(V\), the temperature gradient inside the inhomogeneities is not uniform, although interacting E-inclusions [71] can lead to uniform interior temperature gradients and for specific loadings, non-ellipsoidal inhomogeneities can yield uniform interior temperature gradients, e.g., the counterexample of the Strong Eshelby conjecture given by Liu [71].

Regarding the first point, once the interior temperature gradient field is known, it can be employed to determine the exterior field by using (2.6) so that for \(\mathbf{y}\notin V_{1}\),

where \(\mathcal{A}_{ij}\) is the temperature gradient Concentration tensor linking the interior temperature gradient to that in the far-field, i.e., \(\theta_{j}\), see Sect. 3.3. The gradient of (3.6) is not uniform since \(\mathbf{y}\) now lies outside \(V_{1}\).

3.2 Elastostatics

The symmetry relation \(C_{ijk\ell}=C_{ij\ell k}\) was used in deriving (2.11) as this turns out to be preferable in various contexts. Analogously to the potential problem, let us take homogeneous displacement gradient conditions in the far-field, i.e., as \(|\mathbf{x}|\rightarrow\infty\)

where \(\epsilon _{ij}\) is uniform and therefore \(u^{*}_{i}=\epsilon _{ij}x_{j}\) and \(e^{*}_{ij}=(\epsilon _{ij}+\epsilon _{ji})/2\). Note that \(\epsilon _{ij}\) does not have to be symmetric but if it is then it is simply the strain in the far-field. As in the case of the potential problem, the aim is to determine if there exists an inhomogeneity of any shape that is consistent with the assumption of uniform interior strain. If such an inhomogeneity exists, (2.11) is only consistent for \(\mathbf{y}\in V_{1}\) if the tensor defined as

is uniform. The tensor defined here is the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor for elastostatics. It possesses the minor symmetries \(P_{ijk\ell}=P_{ij\ell k}=P_{jik\ell }\) by construction. Furthermore, thanks to the symmetry of the free space Green’s tensor \(G_{ij}=G_{ji}\) it also possesses the major symmetry \(P_{ijk\ell}=P_{k\ell ij}\).

It transpires that when the inhomogeneity region is ellipsoidal the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor defined in (3.8) is indeed uniform. This is proved in Appendix A.1, where it is also shown that the general form for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor can be defined in terms of an integral over the surface of the unit sphere \(S^{2}\).

That Eshelby’s (weak) conjecture is true for isotropic elastostatics problems [56, 71], means that the ellipsoid is the only shaped inhomogeneity for which the interior temperature gradient is uniform under any such far-field condition of the form (3.7). It is stressed however that it is not yet clear whether the weak conjecture is true in the context of anisotropic problems.

To determine the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor for an ellipsoid for a given host anisotropy one merely has to evaluate the surface integral in (3.9) and this can be done numerically very efficiently. For host anisotropies more complex than transversely isotropic it is generally recommended that the form (3.9) be employed and integrals are evaluated numerically. In what follows here the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor shall be determined in the case of an isotropic host phase by appealing to various symmetries and potential theory. An important result derived by Withers [133] associated with a transversely isotropic host phase is also stated.

As in the potential problem, the only aspects of the inhomogeneity that influence the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are its shape and, for anisotropic host phases, its orientation with respect to the axes of anisotropy of the host phase. Note also that the same three points described for the potential problem, preceding equation (3.6), also hold here in the elastostatics context with appropriate modifications to terminology. Furthermore, once the field is known inside the inhomogeneity region \(V_{1}\) the exterior field can be determined in terms of the Green’s tensor, as

where \(\mathcal{A}_{ijk\ell}\) are the components of the strain Concentration tensor (see Sect. 3.3), which links the strain inside the inhomogeneity to that in the far-field.

3.3 The Potential Gradient Tensor and Strain Concentration Tensor

Defining the volume average

of the function \(f\), it is straightforward to show that in the case of the conditions (3.1), the body averaged temperature gradient is [81]

Of immediate interest is the temperature gradient field \(e^{1}_{i}\) inside an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity \(V_{1}\), which from the theory developed above has been shown to be uniform so that it is equal to its phase average, \(e^{1}_{i}=\overline{e}^{1}_{i}\) where the phase average is defined as

Therefore in the case of an isolated ellipsoidal inhomogeneity with homogeneous far-field conditions of the form (3.1), using (3.14), the expression in (2.7) becomes

Using the symmetries \(C_{ij}=C_{ji}\) and \(P_{ij}=P_{ji}\) and re-arranging, (3.16) can thus be written in the form

Therefore one can relate the uniform temperature gradient inside the inhomogeneity to the average temperature gradient of the entire body via a second order tensor, which is thus identified as the temperature gradient Concentration tensor for this problem.

Note that \(\mathcal{A}_{ij}\) is the Concentration tensor associated with an isolated inhomogeneity inside an unbounded host medium. The calligraphic notation \(\mathcal{A}_{ij}\) has been used to stress the link with (and distinguish from) the exact Concentration tensor whose components are usually defined as \(A_{ij}\), and which links the phase average of the true temperature gradient inside an inhomogeneity to that in the far-field in a complex inhomogeneous medium, which may consist of interacting inhomogeneities. For a dilute medium where interaction effects can be neglected, \(A_{ij}=\mathcal{A}_{ij}\).

Moving on to the elastostatics case, it is straightforward to show that in the case of the conditions (3.7), the body averaged strain is

The (uniform) strain \(e^{1}_{ij}\) inside an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity \(V_{1}\) is thus equal to its phase average, \(e^{1}_{ij}=\overline {e}^{1}_{ij}\). Therefore for an isolated ellipsoidal inhomogeneity with homogeneous far-field conditions (3.7), using (3.20), the expression in (2.11) can be used to determine the expression

where \(I_{ijk\ell}\) is the fourth order identity tensor defined in (C.9). Therefore the uniform strain inside the inhomogeneity can be related to the average strain of the entire body via a fourth order tensor, which is thus identified as the strain Concentration tensor for this problem.

4 The Potential Problem: Specific Cases

4.1 Isotropic Host Phase

Assume that the host phase is isotropic, so that \(C_{ij}^{0}=k_{0}\delta_{ij}\) and therefore the associated free-space Green’s function is

From (3.2) and (1.2) therefore

where \(\varGamma\) is the potential defined by

Note that this is the negative of the Newtonian potential (see for example Kellogg [58]) associated with an ellipsoidal domain \(V_{1}\). From potential theory therefore

and furthermore \(\varGamma(\mathbf{x})\) is a quadratic function of the components of \(\mathbf{x}\) (see Appendix B), illustrating the uniformity of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in this case.

As an aside, note that since the host phase is isotropic, the temperature field exterior to the inhomogeneity is determined via (3.6) so that

This solution tends to \(\theta_{i} y_{i}\) in the far-field, as it should do.

Once \(P_{ij}\) is determined for an isotropic host phase the associated Concentration tensor for an isolated inhomogeneity may then be found from (3.19) as is now illustrated in a number of special cases of specific inhomogeneities with given shape and anisotropy.

4.1.1 Sphere in an Isotropic Host Phase

When \(V_{1}\) is a sphere, it is clear from (4.3) that \(\varGamma (\mathbf{x})\) must be spherically symmetric and hence \(\frac{\partial ^{2}\varGamma }{\partial x_{i}\partial x_{j}}\) must be isotropic (and uniform) and therefore

for some constant \(\gamma \). Note that the form (4.6) is a result of the spherical shape and not any assumption regarding isotropy of the inhomogeneity because such an assumption has not been made. Performing a contraction in (4.6) and using (4.4) with \(\mathbf{x}\in V_{1}\) yields \(\gamma =\frac{1}{3}\). Therefore from (4.2) and (1.2)

For practical purposes, especially for use in micromechanical methods for bounds and estimates of effective material properties, it is useful to write down the associated Concentration tensors.

Isotropic Sphere

If the spherical inhomogeneity is isotropic with conductivity \(C_{ij}^{1}=k_{1}\delta_{ij}\), one can show straightforwardly using (3.19) and properties of second order tensors (see Appendix C.1) that

Anisotropic Sphere

Consider a transversely isotropic sphere where the plane of isotropy is the \(x_{1} x_{2}\) plane. The conductivity tensor therefore takes the form \(C_{ij}^{1} = k_{1}(\varTheta_{ij}+\upsilon\delta_{i3}\delta_{j3})\) where \(\varTheta _{ij}\) is defined according to

and \(\upsilon\) indicates the degree of anisotropy, with \(\upsilon=1\) giving isotropy. Using the result derived in (4.7) and (4.9) together with properties from Appendix C.1, the Concentration tensor \(\mathcal{A}_{ij}\) can be written down in the form

Setting \(\upsilon=1\) recovers the isotropic result (4.8).

Averaging over all orientations of the anisotropy of the inhomogeneity uniformly will yield an isotropic Concentration tensor of the form

where the underline denotes averaging over orientations. By performing this uniform orientation averaging (see Appendix C.3.3) on (4.10) it is straightforwardly shown that

It is also possible to weight the averaging should there be a preferential distribution of anisotropy. Details of how to implement this procedure are given in Appendix C.3.2.

4.1.2 Circular Cylinder in an Isotropic Host Phase

When \(V_{1}\) is a circular cylinder with axis of symmetry in the \(x_{3}\) direction, it is clear that \(\varGamma(\mathbf{x})\) should be independent of \(x_{3}\) and isotropic in the \(x_{1}x_{2}\) plane so that

for some constant \(\gamma \), where \(\varTheta_{ij}\) was defined in (4.9). Performing a contraction in (4.13) and using (4.4) the result \(\gamma =\frac{1}{2}\) is obtained. From (4.2) therefore

If the cylinder is isotropic with conductivity tensor

it is straightforward to show that

Alternatively, suppose that the cylinder is transversely isotropic with conductivity tensor

Interestingly one can show that in this case the Concentration tensor is identical to the isotropic case, i.e., the form stated in (4.16): the parameter \(\upsilon\) does not appear in the Concentration tensor. Of course if the axis of symmetry of transverse isotropy is not aligned with the cylinder axis then this Concentration tensor would then depend on \(\upsilon\).

If the (uniform) orientation average of (4.16) is taken, the associated Concentration tensor is derived:

This last result is often used when very long, thin needle-like inhomogeneities are uniformly distributed and oriented throughout some host medium.

4.1.3 Ellipsoid in an Isotropic Host Phase

Consider now the general case of an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity and as usual denote the semi-axes of the ellipsoid as \(a_{j}\), \(j=1,2,3\). It is straightforward to show, using the theory of the potential, as in Appendix B that for an ellipsoid in an isotropic host phase, the function \(\varGamma(\mathbf{x})\) is quadratic in the components of \(\mathbf{x}\) and can be written in the closed form

where

In Appendix B it is then shown that

where with \(\varepsilon _{n}=a_{3}/a_{n}\),

Therefore

Finally note that using (4.4) it is easily shown that \(\gamma _{1}+\gamma _{2}+\gamma _{3} = 1\).

4.1.4 Spheroid in an Isotropic Host Phase

Denote the semi-axes of the spheroid as \(a_{1}=a_{2}=a\neq a_{3}\) and use this in (B.27) which becomes

where \(\varepsilon =a_{3}/a\). Make the substitution \(\beta =\sin\psi\) to find

noting that \(\varepsilon =1\) is the case of a sphere.

Therefore from (4.19) it is clear that

where

and \(\mathcal{T}(\varepsilon )=\frac{1}{2}(1-\mathcal{S}(\varepsilon ))\). The function \(\mathcal{S}(\varepsilon )\) has taken many forms in the literature but it is felt that this is a most clear, consistent and concise formulation. Note that \(\mathcal{S}(\varepsilon )\rightarrow\frac{1}{3}\) as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow1\) for the spherical case (see further details below).

Using (4.26) in (4.2), the resulting Hill and Eshelby tensors take the form

where \(\gamma _{3}=\mathcal{S}(\varepsilon )\) and \(\gamma =\mathcal{T}(\varepsilon )\).

Expressions for the Concentration tensors associated with the spheroidal inhomogeneity case can now be determined straightforwardly. For an isotropic spheroid,

Averaging uniformly over orientations of the axes of the spheroid yields

One can take limits in the case of the spheroidal inhomogeneity in order to derive the following results, some of which confirm cases considered above. When \(V_{1}\) is

-

(i)

a sphere, i.e., \(\varepsilon \rightarrow1\), it is deduced that \(\gamma =\gamma _{3} = \frac{1}{3}\),

-

(ii)

a cylinder, i.e., \(\varepsilon \rightarrow\infty\), it is deduced that \(\gamma _{3}= 0\), \(\gamma =\frac{1}{2}\),

-

(iii)

a disc or layer, i.e., \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\), it is deduced that \(\gamma _{3}=1\), \(\gamma =0\).

When used in (4.29) (i) and (ii) confirm the results derived for the Concentration tensors for isotropic spheres and cylinders derived in Sects. 4.1.1 and 4.1.2 respectively. One has to be rather careful in taking these limits and for (i) use L’Hopital’s rule appropriately, noting that as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow1\)

In (ii) one has to use the fact that \(\operatorname{arccosh}x\sim\log x\) as \(x\rightarrow\infty\). The result for layers in (iii) can also be obtained via straightforward symmetry arguments.

4.1.5 Limiting Case of an Elliptical Cylinder

One can use the formulation for general ellipsoids above in order to obtain a result for an elliptical cylinder, unbounded in the \(x_{3}\) direction with semi-axes \(a_{1}\) and \(a_{2}\) lying along the \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\) axes respectively. Taking the limit \(a_{3}\rightarrow\infty\) in (B.32), one can show that

where

The integrals can be determined explicitly, noting that with \(i,j=1,2\), \((i\neq j)\)

and therefore

The Hill and Eshelby tensors therefore take the form

As regards the Concentration tensor for an isotropic cylinder with \(C^{1}_{ij}=k_{1}\delta_{ij}\), this is determined in the form

where \(\epsilon =a_{2}/a_{1}\) is the aspect ratio of the ellipse.

4.1.6 Limiting Cases of a Cavity, Penny-Shaped Crack and Ribbon-Crack

It does not make sense to define a temperature gradient Concentration tensor in the context of cracks or cavities because clearly there is no interior field. However it turns out that this concept is useful and can be interpreted as linking the far-field to the field on the surface of such inhomogeneities [50] with an appropriate definition of cavity temperature gradient. Here the results above are used in order to derive associated Concentration tensors for cracks and cavities.

Consider a spheroidal inhomogeneity and the limit \(k_{1}\rightarrow0\) in (4.29). This yields

This is the Concentration tensor for potential problems involving spheroidal cavities.

Next consider the so-called penny-shaped crack limit. The asymptotic form of \(\gamma (\varepsilon )\) and \(\gamma _{3}(\varepsilon )\) as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\) is required. These are easily shown to be

Therefore one can derive the form

where expansions have been taken for \(\varepsilon \ll1\) and terms up to \(O(1)\) have been retained since higher order terms will clearly vanish as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\).

The coefficient of \(\delta_{i3}\delta_{j3}\) in (4.40) involves an apparently singular limit as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\). That this is not a problem arises from the fact that this expression is used in formulae for effective properties of cracked media where this term is always multiplied by a volume-fraction term (or rather a crack-density term) that is proportional to \(\varepsilon \) [48, 49]. Note that taking the limits in the opposite order, i.e., \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\) and then \(k_{1}\rightarrow0\) yields an inconsistent result, giving rise to singular effective material behaviour in the crack limit, which cannot be correct.

Finally, consider a different limit, the so-called ribbon-crack limit. Take \(k_{1}=0\) in the elliptical cylinder result (4.37) to find

Therefore as \(\epsilon \rightarrow0\)

As in the penny-shaped crack result above, the Concentration tensor for the ribbon-crack is singular.

4.2 Anisotropic Host Phase

The general form (3.3) for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor associated with arbitrary host anisotropy requires the necessary surface integral to be evaluated. In the case of transversely isotropic and orthotropic media however, where principal axes are aligned with the semi-axes of the ellipsoid, the problem can be simplified significantly by employing a scaling of the Cartesian variables in order to reduce the isolated ellipsoidal inhomogeneity problem in an anisotropic medium to the case of an ellipsoidal inhomogeneity (with different semi-axes) in an isotropic medium. Therefore the results derived above for the isotropic host phase case can be used in the scaled domain and then mapped back to the physical domain in order to obtain the appropriate physical Hill and Eshelby tensors.

As usual consider the case of an ellipsoid with semi-axes \(a_{j}, j=1,2,3\) but now embedded in an orthotropic host medium (with principal axes aligned along \(x_{j}\), i.e., with the semi-axes of the ellipsoid) so that

where \(\upsilon_{2}=1\) (or \(\upsilon_{3}=1\)) for transverse isotropy. The governing partial differential equation is

Now employ the simple rescaling

where \(\upsilon_{1}=1\) is introduced for notational convenience (the conductivity along the \(x_{1}\) axis is thus \(k_{0}\)), so that the semi-axes of the ellipsoid in the mapped domain become \(\hat{a}_{j}=a_{j}/\sqrt {\upsilon_{j}}, j=1,2,3\) and the scaled ellipsoid is denoted as \(\hat {V}_{1}\). The governing equation then becomes that governing isotropic media so that

where \(\hat{\varGamma}(\hat{\mathbf{x}})\) is defined in terms of the isotropic (due to scaling) Green’s tensor as defined in (4.1) but now integrated over the scaled ellipsoid \(\hat {V}_{1}\), i.e.,

As a consequence for a general ellipsoid, the result (B.29) can be used but with \(x_{j}\) replaced by \(\hat{x}_{j}\) and \(a_{j}\) replaced by \(\hat{a}_{j}, j=1,2,3\). Therefore with reference to (4.22)

where \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{n}=\hat{a}_{3}/\hat{a}_{n}\). The \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\)-tensors for an ellipsoid embedded inside an orthotropic host medium can then be written as

where \(\gamma _{n} = \frac{1}{\upsilon_{n}}\mathcal{E}(\hat{\varepsilon }_{n};\hat {\varepsilon }_{1},\hat{\varepsilon }_{2})\).

Note that the above scaling approach is considerably simpler than carrying out the necessary integrals in the corresponding general expression (3.3) for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor. If the inhomogeneity is embedded in a transversely isotropic host phase with conductivity tensor

then the (orthotropic) \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor for an ellipsoid with semi-axes aligned with the principal directions of anisotropy is found by setting \(\upsilon_{1}=\upsilon_{2}=1\) and \(\upsilon_{3}=\upsilon\) in (4.49) above. Simplifications arise for a spheroid of course as shall now be illustrated.

4.2.1 Spheroid in a Transversely Isotropic Host Phase

Consider a spheroid in a transversely isotropic medium where the major/minor axis of the spheroid is aligned with the axis of transverse isotropy of the host phase. Denote the semi-axes of the spheroid as \(a=a_{1}=a_{2}\neq a_{3}\) and the axis of transverse isotropy as \(x_{3}\). The scaling argument above can be used to see immediately that the \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\)-tensors are given by

where with reference to (4.27)

\(\varepsilon =a_{3}/a\) and \(\gamma =\frac{1}{2}(1-\upsilon \gamma _{3})\), the latter being derived by using

for \(\hat{\mathbf{x}}\in V_{1}\).

Assuming the spheroid itself is isotropic with conductivity tensor \(C^{1}_{ij} = k_{1}\delta_{ij}\), and using (4.50) together with the form of \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in (4.51), the Concentration tensor defined in (3.19) can be straightforwardly determined as

with \(\gamma \) and \(\gamma _{3}\) as defined above. Alternatively, supposing that the spheroid is now transversely isotropic with the same axis of symmetry as the host, i.e., \(C^{1}_{ij} = k_{1}(\varTheta_{ij}+\zeta \delta_{i3}\delta _{j3})\), one finds that

4.2.2 Circular Cylinder in a Transversely Isotropic Host Phase

The circular cylinder limit can be taken in the spheroid case considered in Sect. 4.2.1 where the cross-section of the cylinder sits in the plane of isotropy of the host medium. It is then anticipated that the \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\)-tensors will be transversely isotropic. It has been discussed above that \(\mathcal{S}(x)\rightarrow0\) as \(x\rightarrow0\) and therefore as with the isotropic host case from (4.52) \(\gamma _{3}\rightarrow0\). Therefore \(\gamma =\frac {1}{2}(1-\nu \gamma _{3})= \frac{1}{2}\) and then

so that in fact this tensor is unchanged from the case of an isotropic host phase as in (4.14). The Concentration tensor for an isotropic cylinder can be straightforwardly determined as

The Concentration tensor associated with a transversely isotropic cylinder is also given by that in (4.57).

An interesting non-standard example is the case of a spheroid embedded inside a transversely isotropic host phase where the axes of symmetry and semi-axes are not coincident. In this case the general (surface integral) form of the \(\mathbf{P}\) and \(\mathbf{S}\)-tensors must be used with the semi-axes aligned with the \(\mathbf{x}\) axes but with all components of the modulus tensor being generally non-zero.

4.2.3 Ellipsoid in an Orthotropic Host Phase

Consider an ellipsoid with semi-axes \(a_{j}, j=1,2,3\) that are aligned with the axes of anisotropy of the host medium with orthotropic conductivity tensor as defined in (4.43). Analogous scaling arguments can be used as above in order to scale this problem into an ellipsoid in an isotropic host and then scale back to the physical domain, as described above to show that

where

where \(\upsilon_{1}=1\) and noting that \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{n} = \sqrt{\frac {\upsilon_{n}}{\upsilon_{3}}}\varepsilon _{n}\) where \(\varepsilon _{n}=\frac{a_{3}}{a_{n}}\).

For reference, \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensors for a variety of problems are summarized in Table 1.

5 Elastostatics: Specific Cases

5.1 Isotropic Host Phase

For the case of an isotropic host phase case the elastic modulus tensor is defined as

in terms of the isotropic fourth order basis tensors as defined in (C.7) and (C.8). Here \(\kappa _{0}\) and \(\mu_{0}\) are the bulk and shear moduli of the host, noting the relation to Poisson’s ratio \(\nu_{0}\)

The appropriate isotropic Green’s tensor is

and the expression for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in (3.8) therefore becomes

The potential \(\varGamma\) is that already encountered and defined in (4.3) and \(\varPsi\) is defined by

which satisfies (see for example Kellogg [58])

Once \(P_{ijk\ell}\) is determined, the components of the Eshelby tensor can be calculated from (1.2) and the associated Concentration tensor can be found from (3.23). Recall that no assumptions have been made regarding the anisotropy of the inhomogeneity. This is not required in order for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor to be determined. The only aspects of the inhomogeneity that influence the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are its shape and, for anisotropic host phases, its orientation with respect to the axes of anisotropy of the host phase.

5.1.1 Sphere in an Isotropic Host Phase

Assume that the host phase is isotropic with elastic modulus tensor given in (5.1) and consider the case where \(V_{1}\) is a sphere. The (uniform) tensors \(\partial ^{2}\varGamma/\partial x_{i}\partial x_{j}\) and \(\partial ^{4}\varPsi/\partial x_{i}\partial x_{j}\partial x_{k}\partial x_{\ell}\) will be spherically symmetric, i.e., isotropic and must possess full symmetry with respect to the interchange of any index. As with the potential problem therefore,

and for \(\varPsi\) the general isotropic form, with the additional constraint regarding symmetry with respect to interchange of any indices, is

where \(\psi\) is a constant to be determined. Performing the contractions \(j=i\), \(\ell=k\) in (5.8) and utilizing (5.6), \(\psi=-2/15\). Using (5.7) and (5.8) in (5.4), the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are

After simplification and writing in terms of the tensors \(I_{ijk\ell }^{1}\) and \(I_{ijk\ell}^{2}\) this becomes

where upon using the relationship (5.2) the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are determined as

From this form the Eshelby tensor is easily determined via (1.2) as

where

Isotropic Sphere

The \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor derived in (5.10) holds for a spherical inhomogeneity of arbitrary anisotropy, embedded inside an isotropic host phase. If the inhomogeneity is also assumed isotropic with elastic modulus tensor of the form

one can use (C.9) and the contraction properties of the tensors \(I_{ijk\ell}^{1}, I_{ijk\ell}^{2}\) as defined in Appendix C.2 in order to write

Finally the inversion properties of such a tensor are employed (as described in Appendix C.2.3) together with (5.11) in order to obtain the strain Concentration tensor:

Taking \(\kappa _{1}, \mu_{1}\rightarrow0\) in (5.16) the Concentration tensor for a spherical cavity is obtained purely in terms of the host Poisson ratio:

Cubic Sphere

Assume now that the sphere has cubic symmetry with elastic modulus tensor

where

Instead of (5.15), it is found that

Next, using the form of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in (5.10) and the relationships (C.19), the expression (5.20) becomes

where

Finally, appealing to the theory regarding cubic tensors in Appendix C.2.2 the Concentration tensor is

where

Note that when \(\eta_{1}=0\) the case of an isotropic sphere is recovered as in (5.15).

5.1.2 Circular Cylinder in an Isotropic Host Phase

Now assume that \(V_{1}\) is a circular cylinder with axis of symmetry in the \(x_{3}\) direction. As for the potential problem, \(\varGamma(\mathbf{x})\) must be independent of \(x_{3}\) and isotropic in the \(x_{1}x_{2}\) plane. Hence, as described in (4.13)

Furthermore \(\varPsi\) must also be independent of \(x_{3}\) and be isotropic in the \(x_{1}x_{2}\) plane and hence write

for some constant \(\psi\), where the fact that this tensor should be fully symmetric with respect to interchange of any of its indices has been used. Performing the contractions \(j=i\), \(\ell=k\) and using (5.6) leads to the conclusion that \(\psi=-\frac{1}{4}\). From (5.4) therefore

By writing \(\delta_{ij}=\varTheta_{ij}+\delta_{i3}\delta_{j3}\) in the first term of (5.27) and then recognizing the appropriate Hill transversely isotropic basis tensors (the reader is referred to the discussion of this tensor basis in Appendix C.2.3) that arise as a result of the various contraction terms, the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor can be written in the form

In order to derive the Eshelby tensor one contracts \(\mathbf{P}\) with the host modulus tensor \(\mathbf{C}^{0}\). To do this, write the isotropic basis tensors in terms of the Hill basis tensors using the expressions (C.26)–(C.28) and then use the contractions summarized in Table 2 in order to determine that

It may well be the case that a different tensor basis should be used if it transpires that the cylinder itself is more anisotropic than transversely isotropic, for use in Concentration tensors for example. However for computation, the matrix formulation, as described in Appendix C.4 can be of great utility when anisotropic basis tensors are becoming rather cumbersome.

Suppose now that the cylinder is isotropic with elastic modulus tensor as defined in (5.14). Once again using (C.26)–(C.28), constructing \(\tilde{A}_{ijk\ell}\) is then just a matter of exploiting the contractions in Table 2. It transpires that \(\tilde{\mathcal{A}}_{ijk\ell}\) takes the form

where

Using the inversion expression for transversely isotropic tensors stated in Appendix C.2.3, the appropriate Concentration tensor is thus derived as

where

Since \(\alpha _{2}\neq \alpha _{3}\) it is seen that \(\mathcal{A}_{1133}\neq \mathcal {A}_{3311}\). The circular cylindrical cavity limit can be obtained by setting \(\mu_{1}=0\). Using the expression \(\lambda =2\mu\nu/(1-2\nu)\),

Finally note that the fourth order tensor (5.34) can be represented in matrix form (see Appendix C.4 where the following “square bracket” notation is introduced) as

where

Clearly it is possible to write down explicit expressions for the Concentration tensor when the circular cylinder is anisotropic. This merely complicates the tensorial (or matrix) operations after the derivation of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in (5.27). Given this \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor, perhaps the most important aspect is then to choose the tensor basis set correctly, given the anisotropy of the inhomogeneity. For example, when the cylinder itself is transversely isotropic (a common occurrence in applications) it is considered sensible to use a transversely isotropic tensor basis set. For practical purposes and especially for the sake of computation, using the matrix formulation of tensors is advantageous in cases where the tensor basis sets become rather cumbersome. The following procedure is used, in the usual notation, referring to Appendix C.4, and defining the \(6\times6\) matrix \([P]\) associated with the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor, define

where \([W]\) is defined in (C.56) and therefore

5.1.3 Spheroid in an Isotropic Host Phase

When \(V_{1}\) is a spheroid, the potential theory outlined in Appendix B is once again of use. It is clear that the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor must be transversely isotropic and therefore will take the form

The separate contributions to the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor shall therefore first be decomposed into this form. Firstly, from the potential case described in Sect. 4.1.4

where \(\gamma _{3} = \mathcal{S}(\varepsilon )\) and \(\gamma =\frac{1}{2}(1-\gamma _{3})\). Representing all terms in the Hill basis one can show that

This is seen by using \(\varTheta_{ik}=\delta_{ik}-\delta_{i3}\delta _{k3}\) and writing for example,

Doing this for each term on the left hand side of (5.46), combining and using the definitions of the transversely isotropic basis tensors in Appendix C.2.3 leads to the form on the right hand side of (5.46).

Further, after much algebraic manipulation using the simplifications of the integrals in Appendix B in the case of spheroids one can show that

where, upon using \(\gamma _{3}=1-2\gamma \),

Therefore

A good check is to ascertain that the result for a sphere in an isotropic host phase is recovered by taking \(\varepsilon \rightarrow1\) and using (4.31). This is easily done and yields the result derived in Sect. 5.1.1 associated with a sphere. Another useful limit is to take \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\). Results already derived can be employed, e.g., (4.39), which when used in (5.49)–(5.50) yield

For the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor this then gives

The Eshelby tensor with respect to a transversely isotropic basis, in the form

for either the spheroid with components of \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor (5.51)–(5.53) or the \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\) limit of the spheroid with components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor (5.56)–(5.60) has components that are related directly to the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor via the expressions

Finally, it is straightforward, but rather tedious, to show, using the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor derived in the previous example, that the strain Concentration tensor associated with an isotropic spheroid embedded in an isotropic host phase is

where with \(\Delta=\frac{1}{2}q_{1}q_{4}-q_{2}q_{3}\),

and where

with

The spheroidal cavity result is simply (5.65)–(5.71) with \(\lambda _{1}=\mu_{1}=0\) and so every occurrence of \(\lambda _{d}\) and \(\mu_{d}\) is simply replaced with \(-\lambda _{0}\) and \(-\mu_{0}\) respectively. The result can be obtained in terms of \(\nu_{0}\) alone by using the expression \(\lambda _{0}=2\mu_{0}\nu_{0}/(1-2\nu_{0})\).

The average of the Concentration tensor over uniform orientations of spheroids can be obtained using the result in (C.52) in order to derive an expression of the form

5.1.4 Elastic Layer

The result for the spheroid can be used in order to determine the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor and Concentration tensor for an elastic layer, taking \(\varepsilon =0\) in (5.56)–(5.60),

and Eshelby’s tensor easily follows as

Using the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor the Concentration tensor for an isotropic layer is straightforwardly determined as

5.1.5 Limiting Case of a Penny-Shaped Crack

For a penny shaped crack, terms up to \(O(\varepsilon )\) are retained in (5.56)–(5.60) to obtain

Using this to determine the Concentration tensor with \(\mu_{1}=0\) as in the cavity limit, it is straightforwardly shown that

where terms of \(O(\varepsilon )\) have been neglected in (5.77). This expression has singular behaviour as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\) akin to the potential problem result (4.40) and when deriving effective properties for distributions of cracks, this singular nature is necessary to yield the correct effective behaviour [48]. In fact although \(O(1)\) coefficients have been retained in (5.77) only the singular terms are required in order to determine effective properties. The expression (5.77) corrects the typographical errors given on p. 104 of [81].

A common requirement is the determination of the effective properties of a medium comprising penny shaped cracks that are uniformly distributed and uniformly oriented inside some host material. Using (C.52) the associated Concentration tensor is shown to be

The case of an ellipsoid in an isotropic medium shall now be considered. In order to deal with this generally in a tensor setting, ideally an orthotropic tensor basis should be used. Although it is possible to write down such a basis, details are rather lengthy and in fact for practical computation, it is perhaps most sensible to write down the nine independent components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor and use matrix computations in the manner described after Sect. 5.1.2 above.

5.1.6 Ellipsoid in an Isotropic Host Phase

The nine independent components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor for an ellipsoid can be defined in terms of the function \(\mathcal{E}(\varepsilon _{n};\varepsilon _{1},\varepsilon _{2})\) and the semi-axes ratios \(\varepsilon _{n}\).

The nine independent components of the Eshelby tensor for an ellipsoid in an isotropic medium are usually stated in terms of the four components \(S_{1111}, S_{1122}, S_{1133}\) and \(S_{1212}\) together with cyclic properties of the indices, in terms of \(I_{mn}\) and \(I_{m}\) as defined in (B.42)–(B.45). In turn these lead to expressions in terms of the fundamental integral \(\mathcal{E}(\varepsilon _{n};\varepsilon _{1},\varepsilon _{2})\) via (B.35) and (B.43)–(B.46). Now use (5.4) with (4.21) and (B.48) and employ the properties (B.43)–(B.46) to derive the following compact forms

All other non-zero components are obtained by cyclic permutation of the indices in the above equations. Those components that cannot be obtained via cyclic permutation are zero, e.g., \(P_{1112}=P_{1223}=P_{1323}=0\).

For representations and calculations of the Concentration tensor it is convenient to use the matrix representation of the tensors. This is discussed in the next section by considering the elliptical cylinder and ribbon crack limits. First however the components of the Eshelby tensor are stated, using (1.2) and noting the slightly modified notation for \(I_{mn}\) in (B.42) (i.e., the factor of \(a_{m}^{2}\)) as compared with the standard definition in Mura [92]. The components are expressed as

and permutation rules follow as for the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor.

5.1.7 Elliptical Cylinder and Ribbon-Crack Limit

In Sect. 4.1.5 it was shown that in the limit as \(a_{3}\rightarrow\infty\), \(\mathcal{E}(1;\varepsilon _{1},\varepsilon _{2}) \rightarrow 0\) and

where \(\epsilon =a_{2}/a_{1}\). These are used in the expressions for \(I_{mn}\) and \(I_{n}\) in Appendix B and substituted into (5.79)–(5.82) to determine the associated \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor components. Since the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor is still orthotropic there are nine independent components:

The Eshelby tensor components follow as

noting that Eshelby’s tensor does not possess the major symmetry, unlike Hill’s tensor.

Suppose that the host and elliptical cylinder are both isotropic. In order to determine the Concentration tensor orthotropic tensors are required. Although it is possible to use an orthotropic basis set, it is perhaps most convenient to work with the matrix formulation of the tensors and derive the Concentration tensor using a symbolic mathematical package such as Mathematica. In doing this the matrix formulation \([\mathcal{A}]\) of the tensor \(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}\) is employed as noted in (5.42)–(5.43). The components of the matrix are so long that to list these here would not be beneficial but two very useful limits shall be written down. The elliptical cylindrical cavity limit is obtained by taking \(\mu _{1}\rightarrow0\) which yields a matrix form of the tensor as

where

and taking the limit as \(\epsilon \rightarrow0\) yields the ribbon-crack limit, retaining terms up to \(O(1)\) in \(\epsilon \),

5.1.8 Flat Ellipsoid

Consider the case when \(a_{1}> a_{2}\gg a_{3}\). It is straightforward to take this limit in (B.36)–(B.40) in order to obtain

where with reference to (B.39) and (B.40), \(F(k)\) and \(E(k)\) are introduced as the complete Elliptic integrals of the first and second kind, respectively

and \(k=1-\frac{\varepsilon _{1}^{2}}{\varepsilon _{2}^{2}}\). From (5.111)–(5.113), the \(I_{mn}\) can be straightforwardly determined via (B.43)–(B.46) and thus the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor from (5.79)–(5.82) and (5.83)–(5.86).

5.1.9 Spheroid Limit Check

One can straightforwardly take the spheroidal inhomogeneity limit \(a_{1}=a_{2}=a\neq a_{3}\) in the ellipsoidal result above. In particular it is noted that in the limit as \(a_{1}\rightarrow a_{2}=a\), referring to Sect. 4.1.4,

where \(\varepsilon =a_{3}/a\). This then gives

These can then be used in (5.79)–(5.82) together with the cyclic properties to derive the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor for a spheroid. It is straightforward to check that this gives rise to the coefficients \(p_{1}\) through \(p_{6}\) as defined for a transversely isotropic tensor in (5.51)–(5.53).

5.2 Anisotropic Host Phase

In the potential problem case, scaling coordinate systems assisted in the derivation of results associated with anisotropic media. Although such methods can sometimes lead to modest simplifications in elasticity, the general theory does not lead to any significant advances, certainly for the problems that are of greatest interest in micromechanics. In particular such methods do not lead to significant simplifications for generally transversely isotropic media which is a material symmetry of great importance. Therefore to derive the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensors associated with inhomogeneities in anisotropic host phases, it is best to work with the integral form of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor as defined in (3.9) for an ellipsoid.

Few explicit results are available in general however since the Green’s tensor cannot generally be determined analytically. One of the few that can be determined is that associated with transversely isotropic media. Withers derived the associated Eshelby tensor for a spheroid [133] using the form of the Green’s function determined by Pan and Chou [101] and we state his result here where the semi-major or minor axis of the spheroid is aligned with the axis of transverse isotropy. This result shall then be validated by employing the general integral form (3.9). Only in the last decade have articles started to appear that compute effective properties of composite media with anisotropic inhomogeneities via micromechanical methods (e.g., [42, 116]). It is also important to note specific results for the Eshelby and Hill tensors associated with cracks in anisotropic media, e.g., Gruescu et al. [44] and Barthélémy [9].

5.2.1 Spheroid in a Transversely Isotropic Host Phase

Consider a spheroid with semi-axes \(a=a_{1}=a_{2}\neq a_{3}\) embedded in a transversely isotropic host phase where the \(x_{1}x_{2}\) plane is the plane of isotropy. The elastic modulus tensor of the host is

where

Here \(K_{0}\) and \(m_{0}\) are the in-plane bulk and shear moduli and \(g_{0}\) is the antiplane shear modulus (often \(p_{0}\) is used for the anti-plane modulus but this is not employed here in order to avoid confusion associated with components \(p_{j}\) of the Hill tensor).

Derivation from Withers’ Eshelby Tensor

Withers derived the Eshelby tensor for a spheroid in a transversely isotropic host medium. In order to state this result it is useful to first define the parameters

where \(\hat{\ell}_{0}=(n_{0}(K_{0}+m_{0}))^{1/2}\). Note that for elastic materials \(v_{3}\in\mathbb{R}\), the set of real numbers, but \(v_{1},v_{2}\in\mathbb{C}\), the set of complex numbers, in general, with \(v_{2}=\overline{v_{1}}\), where an overbar denotes the complex conjugate here (not to be confused with the body average!)Footnote 1 For \(v_{i}\in\mathbb{R}\) define

When \(v_{i}\in\mathbb{C}\), either of the cases in \(\mathcal {S}(v_{i}\varepsilon )\) are valid since they are merely an analytic continuation of the function (of \(v_{i}\)) into the complex \(v_{i}\)-plane. Note that in the case of isotropy, \(\ell_{0}=\lambda _{0}=\ell_{0}'\), \(g_{0}=m_{0}=\mu_{0}\), \(\hat{\ell}_{0}=n_{0}=K_{0}+m_{0}=\lambda _{0}+2\mu_{0}\) and thus \(v_{1}=v_{2}=v_{3}=1\). The notation \(I_{i}=I_{i}(1)\) is therefore appropriate for the isotropic case, as already introduced.

For a transversely isotropic host phase defined by elastic properties (5.121) Withers determined the components \(S_{ijk\ell}\) in the form

where

Note that slightly different notation has been used here from that in [133] and in particular the notation \(I_{3}(v_{i})\) has been used whereas [133] used \(I_{2}(v_{i})\) for this term in the corresponding equations. This is done here to preserve the symmetry with the isotropic case above so that as \(v_{i}\rightarrow1\), \(I_{3}(v_{i})\rightarrow I_{3}\).

Via straightforward contraction with the transversely isotropic compliance tensor \(\mathbf{D}_{0}\), i.e., the inverse of (5.121), (1.2) then yields

where \(\Delta=K_{0} n_{0}-\ell_{0}^{2}\). Of course this calculation could also be done with the help of matrices rather than tensor forms. Since the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor is transversely isotropic however it is rather straightforward to write down the transversely isotropic tensor basis forms

where

and similarly for the Eshelby tensor with \(p_{n}\rightarrow s_{n}\) and \(P_{ijk\ell}\rightarrow S_{ijk\ell}\) of course.

Derivation from the Direct Integral Form

As noted above, the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor will itself be transversely isotropic of the form given in (5.137). Using the direct integral formulation of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor (3.9), let the unit vector \(\overline{\boldsymbol{\xi}}\) pointing to the surface of the unit sphere be parametrized by the two angles \(\varphi\in[0,2\pi)\) and \(\vartheta\in[0,\pi)\), so that it takes the form

Therefore, together with (5.121), (3.9) becomes

where

with \(N_{ij}\) defined via \(N_{ik}\tilde{N}_{kj} = \delta_{ij}\). The components of \(\tilde{\mathbf{N}}\) are defined as \(\tilde {N}_{ij}=C_{ijk\ell}^{0}\overline{\xi}_{j}\overline{\xi}_{\ell}\). It is straightforward to implement this in a variety of mathematical packages or programming languages.

Here let us plot the five independent components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor, illustrating that the two approaches (Withers’ explicit form and the direct integral evaluation) described above agree. Let us take the elastic properties (associated with the host phase) to be transversely isotropic and choose the material PZT-7A.Footnote 2 Although realistically this material would normally be chosen as the reinforcing phase in a composite, it is appropriate to illustrate the calculations for a model material. Its properties are (all stated in GPa)

In Figs. 2–3 the components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor are plotted, using the explicit form arising from the Eshelby tensor and using the direct evaluation of the integral in order to confirm the results.

Plot of the components \(P_{1111}\) (solid black), \(P_{3333}\) (dashed blue) and \(P_{1313}\) (dotted red) of the Hill tensor associated with a spheroidal inhomogeneity (varying the aspect ratio \(\varepsilon \)) embedded in the transversely isotropic host phase PZT-7A, using the form of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor derived from the explicit form of the Eshelby tensor for this problem. These explicit results are confirmed by calculating the components at discrete values of the aspect ratio by evaluating the direct integral form of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor given in (5.141). Note that the limiting values as \(\varepsilon \rightarrow \infty\) correspond to the circular cylinder result (5.29) and when \(\varepsilon \rightarrow0\) the layer limit is obtained (Color figure online)

As with Fig. 2 but for the components \(P_{1122}\) (solid black) and \(P_{1133}\) (dashed red) of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor (Color figure online)

Concentration Tensor

Since the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor is known one can now go on to deduce the associated Concentration tensor. First assume that the spheroid is isotropic with elastic modulus tensor

Since the Concentration tensor will be transversely isotropic, it is convenient to write \(C^{1}_{ijkl}\) with respect to the transversely isotropic tensor basis so that

where the \(c^{1}_{n}\) coefficients are defined in terms of the two independent elastic moduli \(\kappa _{1}\) and \(\mu_{1}\):

Let us employ (5.121), together with the form of \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor defined in (5.137). The properties of the transversely isotropic basis tensors \(\mathcal{H}_{ijkl}^{n}\) described in Appendix C.2.3 shall also be exploited (and in particular the contraction properties in Table 2), together with the expressions written down in (C.26)–(C.28). The inverse of the Concentration tensor defined in (3.23) can then be determined in the form

where upon defining \(c_{n}=c^{1}_{n}-c^{0}_{n}\),

The tensor \(\tilde{\mathcal{A}}_{ijkl}\) is then inverted, following the procedure in Appendix C.2.3, to yield the Concentration tensor

where

Alternatively suppose that the inhomogeneity is transversely isotropic with the same symmetry axis as the host so that it possesses the elastic modulus tensor of the form (5.145) but where now the constants \(c^{1}_{n}\) are defined in terms of the 5 independent components of this tensor. Then the Concentration tensor is again defined by (5.151) but of course now with the \(c^{1}_{n}\) associated with the transversely isotropic cylinder. This indicates the merit of using the above notation since one can still use (5.151)–(5.153) in this case, merely modifying the \(c^{1}_{n}\) to account for the transverse isotropy of the cylinder.

As usual, the matrix form of these fourth order tensors can be employed for computational efficiency when the problems lack simple symmetries.

5.2.2 Circular Cylinder in a Transversely Isotropic Host

Suppose now that the inhomogeneity is a circular cylinder with its cross-section residing in the plane of isotropy of the transversely isotropic host phase. One can arrive at the corresponding \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor in two ways. The first is to take the limit \(\varepsilon =a_{3}/a\rightarrow\infty\) in the prolate spheroid case in Sect. 5.2.1. The second way is to recognize that since the anisotropy of the host will not affect the in-plane components of the \(\mathbf{P}\)-tensor, the tensor will simply be the same as that for an isotropic host as derived in Sect. 5.1.2 but the elastic properties are modified via \(\lambda _{0}+\mu_{0}\rightarrow K_{0}\) and \(\mu_{0}\rightarrow m_{0}\) for in-plane components and \(\mu _{0}\rightarrow g_{0}\) for the anti-plane component. Therefore, from (5.29)

The Concentration tensor may then be derived by using these coefficients in (5.149)–(5.150) and the expressions that follow.

6 Discussion

6.1 Association with Micromechanics

One of the primary reasons for deriving the Hill or Eshelby tensors and associated Concentration tensors is to understand a multitude of aspects of the behaviour of inhomogeneous media, including their macroscopic constitutive response and so-called effective properties. Following a relatively straightforward argument regarding volume averaging, the effective modulus tensor \(\mathbf{C}^{*}\) of an \(n+1\) phase medium with a distinguishable host phase (phase 0) can be stated as [81, 132]