Abstract

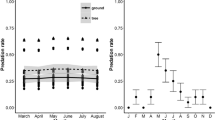

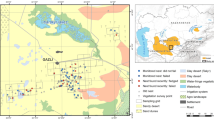

Nest abandonment prior to laying is poorly understood and rarely studied. One possible explanation is that it is a behavior which may have evolved in response to high predation risk in nesting birds as a strategy to avoid the even greater costs of losing eggs or chicks. We tested this hypothesis in the Grey Fantail (Rhipidura albiscapa), a species that builds and abandons multiple nests throughout its breeding season without laying eggs. We placed artificial nests (that contained natural and plasticine eggs) in the exact locations of natural nests from the previous breeding season (spanning a large elevational gradient) for which the fate was known (abandoned, predated, or fledged). Trials were conducted early and late in the breeding season to test for temporal patterns. We postulated that should nest abandonment indeed reduce predation risk, then artificial nests placed at previously abandoned nest sites should have a greater risk of predation than nests placed at predated or fledged nest sites. Overall, we found that 74% of artificial nests were predated, with predation attributed to birds (66%), small mammals (7%), ants (8%), and unknown predators (19%). Artificial nest predation varied according to previous nest fate, whereby predation rates were lowest for predated sites, slightly higher for fledged, and highest at previously abandoned nest sites. In addition, cover increased survival rates for all nest site types. However, we observed a shift in the proportion of nests predated by birds versus other predator taxa, whereby nest predation by birds was highest late in the season at high elevation; this increase may have been due to extreme high temperatures at low elevation resulting in bird predators moving to refuges at higher elevation.

Zusammenfassung

Das Verlassen von Nestern durch die Altvögel vor der Eiablage – eine Strategie zum Minimieren des Prädationsrisikos? Das Verlassen des Nests vor der Eiablage ist ein Verhalten, das bei nistenden Vögeln als Reaktion auf ein hohes Prädationsrisiko evolviert sein könnte, um noch größere Kosten durch den Verlust von Eiern oder Jungvögeln zu vermeiden, doch ist dies nur schlecht verstanden und bislang kaum untersucht worden. Wir haben diese Hypothese beim Graufächerschwanz (Rhipidura albiscapa) untersucht, einer Art, die in einer Brutsaison mehrere Nester baut und wieder verlässt, ohne Eier gelegt zu haben. Hierfür haben wir künstliche Nester (die echte Eier sowie Kneteier enthielten) an Standorten angebracht, an denen sich in der vorherigen Brutsaison natürliche Nester befunden hatten. Diese Standorte erstreckten sich über einen weiten Höhengradienten, und das „Schicksal“der dort zuvor vorhandenen Nester (verlassen, ausgeraubt oder ausgeflogen) war bekannt. Die Experimente wurden sowohl früh als auch spät in der Brutsaison durchgeführt, um zeitliche Muster zu überprüfen. Reduziert das Verlassen von Nestern in der Tat das Prädationsrisiko, sollte das Prädationsrisiko für künstliche Nester an Standorten, an denen Nester im Vorjahr verlassen worden waren, höher sein als für Nester an Standorten, an denen vorherige Nester ausgeraubt worden oder ausgeflogen waren. Insgesamt wurden 74% der künstlichen Nester ausgeraubt, davon 66% durch Vögel, 7% durch Kleinsäuger, 8% durch Ameisen und 19% durch unbekannte Räuber. Wir beobachteten, dass die Prädation der künstlichen Nester entsprechend dem Schicksal vorheriger Nester für zuvor verlassene und ausgeflogene Nester variierte, wobei die Prädationsraten am niedrigsten bei ausgeraubten, etwas höher bei ausgeflogenen und am höchsten bei verlassenen vorherigen Nestern waren. Des Weiteren erhöhte eine Tarnung des Nests die Überlebensraten an allen Standorten. Wir beobachteten jedoch eine Verschiebung im Anteil der Nester, die von Vögeln relativ zu anderen Prädatoren ausgeraubt wurden: Nestprädation durch Vögel war am höchsten spät in der Saison an höhergelegenen Standorten, was mit den extrem hohen Temperaturen an niedriger gelegenen Standorten zusammenhängen könnte. Diese könnten dazu geführt haben, dass Vogelprädatoren in größeren Höhenlagen Schutz vor der Hitze suchten.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alonso JC, Palacín C, Alonso JA, Martín CA (2009) Post-breeding migration in male great bustards: low tolerance of the heaviest Palaearctic bird to summer heat. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 63:1705–1715

Beckmann C, Martin K (2016) Testing hypotheses on the function of repeated nest abandonment as a life history strategy in a passerine bird. Ibis 158:335–342

Beckmann C, McDonald PG (2016) Placement of re-nests following predation: are birds managing risk? Emu 116:9–13

Beckmann C, Biro PA, Martin K (2015) Hierarchical analysis of avian re-nesting behavior: mean, across-individual, and intra-individual responses. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 69:1631–1638

Berger-Tal R, Berger-Tal O, Munro K (2010) Nest desertion by grey fantails during nest building in response to perceived predation risk. J Field Ornithol 81:151–154

Burnham PK, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multimodal inference, 2nd edn. Springer Publications Inc., New York

Campbell A (1900) Nests and eggs of Australian birds, vol 1. Wren Publishing Pty Ltd, Melbourne

Caro T (2005) Antipredator defenses in birds and mammals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Collias NE, Collias EC (1971) Some observations on behavioral energetics in the village weaverbird I. Comparison of colonies from two subspecies in nature. Auk 88:124–133

Collias NE, Victoria JK, Coutlee EL, Graham M (1971) Some observations on behavioral energetics in the village weaverbird II. All-day watches in an aviary. Auk 88:133–143

Colombelli-Negrel D, Kleindorfer S (2009) Nest height, nest concealment, and predator type predict nest predation in Superb Fairy-Wrens (Malurus cyaneus). Ecol Res 24:921–928

Coulson J (1956) Mortality and egg production of the meadow pipit with special reference to altitude. Bird Study 3:119–132

Elkins N (2010) Weather and bird behaviour. A & C Black Publishers Ltd, London

Fisher RJ, Wiebe KL (2006) Breeding dispersal of Northern Flickers Colaptes auratus in relation to natural nest predation and experimentally increased perception of predation risk. Ibis 148:772–781

Fontaine JJ, Martel M, Markland HM, Niklison AM, Decker KL, Martin TE (2007) Testing ecological and behavioral correlates of nest predation. Oikos 116:1887–1894

Forstmeier W, Weiss I (2004) Adaptive plasticity in nest-site selection in response to changing predation risk. Oikos 104:487–499

Fulton GR, Ford HA (2003) Quail eggs, modelling clay eggs, imprints and small mammals in an Australian woodland. Emu 103:255–258

Gauthier M, Thomas DW (1993) Nest site selection and cost of nest building by Cliff Swallows (Hirundo pyrrhonota). Can J Zool 71:1120–1123

Halupka K, Greeney HF (2009) The influence of parental behavior on vulnerability to nest predation in tropical thrushes of an Andean cloud forest. J Avian Biol 40:658–661

Higgins P, Peter J, Cowling S (2006) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic birds. Volume 7: boatbill to starlings, vol 7. Oxford University Press, Melbourne

Hille SM, Cooper CB (2015) Elevational trends in life histories: revising the pace-of-life framework. Biol Rev 90:204–213

Leonard ML, Picman J (1987) The adaptive significance of multiple nest building by male Marsh Wrens. Anim Behav 35:271–277

Li P, Martin TE (1991) Nest-site selection and nesting success of cavity-nesting birds in high elevation forest drainages. Auk: 108:405–418

Lima SL (2009) Predators and the breeding bird: behavioral and reproductive flexibility under the risk of predation. Biol Rev 84:485–513

Maddox JD, Weatherhead PJ, Yasukawa K (2006) Nests without eggs: abandonment or cryptic predation? Auk 123:135–140

Mainwaring MC, Hartley IR (2013) The energetic costs of nest building in birds. Avian Biol Res 6:12–17

Martin TE (1993) Nest predation and nest sites. Bioscience 43:523–532

Martin TE, Briskie JV (2009) Predation on dependent offspring. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1168:201–217

Martin TE, Li P (1992) Life history traits of open- vs. cavity-nesting birds. Ecology 73:579–592

Martin TE, Roper JJ (1988) Nest predation and nest-site selection of a western population of the Hermit Thrush. Condor 90:51–57

Martin TE, Scott J, Menge C (2000) Nest predation increases with parental activity: separating nest site and parental activity effects. Proc R Soc Lond B 267:2287–2293

McGuire A, Kleindorfer S (2007) Nesting success and apparent nest-adornment in diamond firetails (Stagonopleura guttata). Emu 107:44–51

McKinnon L, Smith PA, Nol E, Martin JL, Doyle FI, Abraham KF, Gilchrist HG, Morrison RIG, Bêty J (2010) Lower predation risk for migratory birds at high latitudes. Science 327:326–327

Munro K (2007) Breeding behaviour and ecology of the Grey Fantail (Rhipidura albiscapa). Aust J Zool 55:257–265

Nilsson SG (1984) The evolution of nest-site selection among hole-nesting birds: the importance of nest predation and competition. Ornis Scand 15:167–175

Noske R, Mulyani Y, Lloyd P (2013) Nesting beside old nests, but not over water, increases current nest survival in a tropical mangrove-dwelling warbler. J Ornithol 154:517–523

Rangen SA, Clark RG, Hobson KA (2000) Visual and olfactory attributes of artificial nests. Auk 117:136–146

Remeš V (2005) Nest concealment and parental behaviour interact in affecting nest survival in the Blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla): an experimental evaluation of the parental compensation hypothesis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 58:326–332

Remeš V, Matysiokova B, Cockburn A (2012) Long-term and large-scale analyses of nest predation patterns in Australian songbirds and a global comparison of nest predation rates. J Avian Biol 43:435–444

Ricklefs RE (1969) An analysis of nesting mortality in birds. Smithsonian Contr Zool 9:1–48

Saffer TG (2004) A unified approach to analyzing nest success. Auk 212:526–540

SAS Institute (2012) SAS/STAT. User’s guide, Version 9.2, 4th edn, vol 1. SAS Institute, Cary

Skutch AF (1985) Clutch size, nesting success, and predation on nests of Neotropical birds, reviewed. Ornithol Monogr 36:575–594

Slater P, Slater P, Slater R (1986) The Slater field guide to Australian birds. Griffin Press, Adelaide

Zanette L (2002) What do artificial nests tells us about nest predation? Biol Conserv 103:323–329

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for their help and contributions throughout the study: C. Mizzi, R. Collins, J. Evans, R. Pedler, M. Burr, J. Endler, S. Beebe, S. Micallef, J. Smyth, K. Spilstead, J. Hightower. R. Fisher provided statistical advice. We thank the rangers at Mt. Buffalo National Park for logistical support. Dr. K. Rowe and Dr. K. M. Roberts from Museum Victoria assisted with the identification of predator marks on artificial eggs. We thank two anonymous reviews for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Funding was provided by an Alfred Deakin Research Postdoctoral Fellowship to C. Beckmann, and an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship to P. Biro. The research was conducted in compliance with ethical guidelines and the current laws of Australia. This work was completed under protocols approved by the DU Animal Ethics Committee and the Department of Sustainability and Environment of the state of Victoria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flegeltaub, M., Biro, P.A. & Beckmann, C. Avian nest abandonment prior to laying—a strategy to minimize predation risk?. J Ornithol 158, 1091–1098 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-017-1470-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-017-1470-7