Abstract

Objective

To analyze the contribution of ultra-processed foods to the intake of free sugars among different age groups in Australia.

Methods

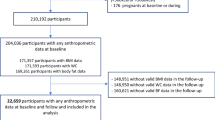

Dietary intakes of 12,153 participants from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (2011–12) aged 2+ years were evaluated. Food items collected through two 24-h recalls were classified according to the NOVA system. The contribution of each NOVA food group and their subgroups to total energy intake was determined by age group. Mean free sugar content in diet fractions made up exclusively of ultra-processed foods, or of processed foods, or of a combination of un/minimally processed foods and culinary ingredients (which includes table sugar and honey) were compared. Across quintiles of the energy contribution of ultra-processed foods, differences in the intake of free sugars, as well as in the prevalence of excessive free sugar intake (≥ 10% of total energy) were examined.

Results

Ultra-processed foods had the highest energy contribution among children, adolescents and adults in Australia, with older children and adolescents the highest consumers (53.1% and 54.3% of total energy, respectively). The diet fraction restricted to ultra-processed items contained significantly more free sugars than the two other diet fractions. Among all age groups, a positive and statistically significant linear association was found between quintiles of ultra-processed food consumption and both the average intake of free sugars and the prevalence of excessive free sugar intake.

Conclusion

Ultra-processed food consumption drives excessive free sugar intake among all age groups in Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization (2015) Guideline: sugars intake for adults and children. World Health Organization, Geneva

Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB (2013) Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 98:1084–1102

Sheiham A, James WP (2014) A reappraisal of the quantitative relationship between sugar intake and dental caries: the need for new criteria for developing goals for sugar intake. BMC Public Health 14:863

Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J (2012) Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 346:e7492

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Baraldi LG, Jaime PC (2019) Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 22(5):936–941

Martínez Steele E, Baraldi LG, Louzada ML, Moubarac JC, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA (2016) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6:e009892

Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Monteiro CA, Levy RB (2019) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and its association with added sugar content in the diets of US children, NHANES 2009–2014. Pediatr Obes 30:e12563

Rauber F, da Costa Louzada ML, Steele EM, Millett C, Monteiro CA, Levy RB (2018) Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic noncommunicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients 10(587):1–12

Moubarac JC, Batal M, Louzada ML, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro CA (2017) Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite 108:512–520

Cediel G, Reyes M, da Costa Louzada ML, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro CA, Corvalán C, Uauy R (2018) Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the Chilean diet (2010). Public Health Nutr 21:125–133

Parra DC, Costa-Louzada ML, Moubarac J-C, Bertazzi-Levy R, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Monteiro CA (2019) The association between ultraprocessed food consumption and the nutrient profile of the Colombian diet in 2005. Salud Pública Méx 61(2):147–154

Louzada MLDC, Ricardo CZ, Steele EM, Levy RB, Cannon G, Monteiro CA (2018) The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 21:94–102

Probst YC, Dengate A, Jacobs J, Louie JC, Dunford EK (2017) The major types of added sugars and non-nutritive sweeteners in a sample of Australian packaged foods. Public Health Nutr 20:3228–3233

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Australian health survey: consumption of added sugars, 2011–12. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, ACT

Lei L, Rangan A, Flood VM, Louie JC (2016) Dietary intake and food sources of added sugar in the Australian population. Br J Nutr 115:868–877

Machado PP, Steele EM, Levy RB, Sui Z, Rangan A, Woods J, Gill T, Scrinis G, Monteiro CA (2019) Ultra-processed foods and recommended intake levels of nutrients linked to non-communicable diseases in Australia: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9:e029544

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013) Australian health survey: users’ guide, 2011–13 Canberra. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Chapter2002011-13. Accessed 12 Jan 2016

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (2014) AUSNUT 2011–2013: Food composition database. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/pages/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Jan 2016

Harttig U, J Haubrock, S Knüppel, H Boeing, E Consortium (2011) The MSM program: web-based statistics package for estimating usual dietary intake using the multiple source method. Eur J Clin Nutr 65(Suppl 1):S87–S91

Johnson BJ, Bell LK, Zarnowiecki D, Rangan AM, Golley RK (2017) Contribution of discretionary foods and drinks to australian children’s intake of energy, saturated fat, added sugars and salt. Children (Basel) 4(12):1–14

Te Morenga LA, Howatson AJ, Jones RM, Mann J (2014) Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. Am J Clin Nutr 100:65–79

Venn D, Banwell C, Dixon J (2017) Australia’s evolving food practices: a risky mix of continuity and change. Public Health Nutr 20:2549–2558

Baraldi LG, Martinez Steele E, Canella DS, Monteiro CA (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and associated sociodemographic factors in the USA between 2007 and 2012: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 8:e020574

Vandevijvere S, De Ridder K, Fiolet T, Bel S, Tafforeau J (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed food products and diet quality among children, adolescents and adults in Belgium. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1870-3

Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC (2018) The UN decade of nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr 21:5–17

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2015) Guidelines on the collection of information on food processing through food consumption surveys. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Austalian Department of Health (2018) Healthy Food Partnership Reformulation Program: Evidence Informing the Approach, Draft Targets and Modelling Outcomes. Australian Government Department of Health, Camberra

Yeung CHC, Gohil P, Rangan AM, Flood VM, Arcot J, Gill TP, Louie JCY (2017) Modelling of the impact of universal added sugar reduction through food reformulation. Sci Rep 7:17392

Scrinis G, Monteiro CA (2018) Ultra-processed foods and the limits of product reformulation. Public Health Nutr 21:247–252

Borges MC, Louzada ML, de Sá TH, Laverty AA, Parra DC, Garzillo JM, Monteiro CA, Millett C (2017) Artificially sweetened beverages and the response to the global obesity crisis. PLoS Med 14:e1002195

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016) Plates, pyramids, planet. developments in national healthy and sustainable dietary guidelines: a state of play assessment. FAO/University of Oxford. Rome

Cowburn G, Stockley L (2005) Consumer understanding and use of nutrition labelling: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 8:21–28

Austalian Department of Health (2019) Labelling of added sugar Australia. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mc17-019936-labelling-of-added-sugar. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Khandpur N, Swinburn B, Monteiro CA (2018) Nutrient-based warning labels may help in the pursuit of healthy diets. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26:1670–1671

Veerman JL, Sacks G, Antonopoulos N, Martin J (2016) The impact of a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages on health and health care costs: a modelling study. PLoS One 11:e0151460

Hernández-F M, Batis C, Rivera JA, Colchero MA (2019) Reduction in purchases of energy-dense nutrient-poor foods in Mexico associated with the introduction of a tax in 2014. Prev Med 118:16–22

World Health Organization (2016) Taxes on sugary drinks: Why do it? apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/260253/1/WHO-NMH-PND-16.5Rev.1-eng.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2019

Obesity Policy Coalition (2017) Policies for tackling obesity and creating healthier food environments: scorecard and priority recommendations for the Australian Federal Government. http://www.opc.org.au/downloads/food-policy-index/AUST-summary-food-epi-report.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb 2019

World Health Organization (2018) Healthy diet. Fact sheet N 394. World Health Organization, Geneva

Mendonça RD, Pimenta AM, Gea A, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Lopes AC, Bes-Rastrollo M (2016) Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 104:1433–1440

Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R et al (2019) Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab 30(1):67–77

Rauber F, Campagnolo PD, Hoffman DJ, Vitolo MR (2015) Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children’s lipid profiles: a longitudinal study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 25:116–122

Mendonça RD, Lopes AC, Pimenta AM, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M (2017) Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a Mediterranean cohort: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am J Hypertens 30:358–366

Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C, Deschasaux M, Fassier P, Latino-Martel P, Beslay M, Hercberg S, Lavalette C, Monteiro CA, Julia C, Touvier M (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ 360:k322

Kim H, Hu EA, Rebholz CM (2019) Ultra-processed food intake and mortality in the USA: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994). Public Health Nutr 22(10):1777–1785

Schnabel L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Touvier M, Srour B, Hercberg S, Buscail C, Julia C (2019) Association between ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of mortality among middle-aged adults in France. JAMA Intern Med 179(4):490–498

Ni Mhurchu C, Brown R, Jiang Y, Eyles H, Dunford E, Neal B (2016) Nutrient profile of 23 596 packaged supermarket foods and non-alcoholic beverages in Australia and New Zealand. Public Health Nutr 19:401–408

Moubarac JC, Parra DC, Cannon G, Monteiro CA (2014) Food classification systems based on food processing: significance and implications for policies and actions: a systematic literature review and assessment. Curr Obes Rep 3(2):256–72

Moubarac JC, Parra DC, Cannon G, Monteiro CA (2014) Food classification systems based on food processing: significance and implications for policies and actions: a systematic literature review and assessment. Curr Obes Rep 3:256–272

Livingstone MB, Robson PJ (2000) Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc 59:279–293

Börnhorst C, Bel-Serrat S, Pigeot I, Huybrechts I, Ottavaere C, Sioen I, De Henauw S, Mouratidou T, Mesana MI, Westerterp K, Bammann K, Lissner L, Eiben G, Pala V, Rayson M, Krogh V, Moreno LA, Consortium I (2014) Validity of 24-h recalls in (pre-)school aged children: comparison of proxy-reported energy intakes with measured energy expenditure. Clin Nutr 33:79–84

Lafay L, Mennen L, Basdevant A, Charles MA, Borys JM, Eschwège E, Romon M (2000) Does energy intake underreporting involve all kinds of food or only specific food items? Results from the Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Santé (FLVS) study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24:1500–1506

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Machado, P.P., Steele, E.M., Louzada, M.L.C. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption drives excessive free sugar intake among all age groups in Australia. Eur J Nutr 59, 2783–2792 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02125-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02125-y