Abstract

In this paper we study the co-existence of two well known trading protocols, bargaining and price-posting. To do so we consider a frictional environment where buyers and sellers play price-posting and bargaining games infinitely many times. Sellers switch from one market to the other at a rate that is proportional to their payoff differentials. Given the different informational requirements associated with these two trading mechanisms, we examine their possible co-existence in the context of informal and formal markets. Other than having different trading protocols, we also consider other distinguishing features. We find a unique stable equilibrium where price-posting (formal markets) and bargaining (informal markets) co-exist. In a richer environment where both sellers and buyers can move across markets, we show that there exists a unique stable dynamic equilibrium where formal and informal activities also co-exist whenever sellers’ and buyers’ net costs of trading in the formal market have opposite signs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

With homogenous reservation prices and small markets, however, Julien et al. (2002) show that auctions are preferred by sellers.

Lu and McAfee (1996) point out “in markets where bargaining persists, there must be some factors which make bargaining preferable to auctions. The effects of such factors must be strong enough to override the structural advantages of auctions”. Similarly, Kultti (1999) points out that “even though auctions and posted prices turn out to be equivalent one rarely sees auction markets”.

The recent New Monetarist literature considers trading mechanisms and matching technologies as part of their environment; see, for instance, (Lagos and Wright 2005).

The vast majority of informal sector activities involves goods and services whose production and distribution are perfectly legal. The informal sector merely seeks to evade taxes and regulations. Clearly, illegal goods are also an important component of the informal economy. But we have chosen not to incorporate them, as the literature has not yet come to an agreement on how to model them. We refer to the reader to Feige (1990), De Soto (1989) and Portes et al. (1989), among others, for more on informal markets.

It is important to note that informative advertising, which coincides with the inception of price-posting, is an essential feature for this trading institution to be effective. In price posting, sellers need to send informative signals describing their product, price and location in order to attract buyers, as documented by Bagwell (2007).

Auctions are clearly not suitable for informal markets as auctions are, by definition, public events.

Note that since formal sellers are in fixed locations and are publicly observed by buyers and authorities, formal sellers can credibly provide such contracts. This practice is consistent with anti-lemon laws enforcing certain money-back guarantees prevalent in the formal markets in real life. In contrast, informal sellers cannot credibly provide such assurances to their customers, as they do not legally exist.

Conversely, sellers will switch from the informal to the formal market whenever the opposite changes occur.

The use of auctions has traditionally been motivated by the existence of a monopoly seller possessing imperfect information about the buyers’ valuations of the object for sale. On the other hand, price-posting has usually been motivated by the sale of goods the value, which is commonly understood, no bidding takes place, and the good may be rationed according to some rule.

In particular, Rauch (1991) considers an environment with a minimum wage policy that can only be enforced for sufficiently large firms. This results in smaller firms operating in the informal sector and paying lower wages. Meanwhile, Nicolini (1998) shows how inflation is optimal when tax evasion in the informal market is widespread, as income generated by cash is difficult to monitor by tax authorities.

Note, that when more than one buyer visits a seller, the seller needs to select which buyer to sell the good. For more details, we refer to Burdett et al. (2001).

In an alternative interpretation of our model, there are no separate populations of formal and informal agents. All agents participate in both formal and informal markets, where informal transactions are cash-only. In this interpretation, \(s^{_{\text {fo}}}\) (\(s^{_{\text {in}}}\)) denotes the fraction of each seller’s transactions that are formal (informal). The equilibria in our model then correspond to mixed strategy Nash equilibria. See Remarks 2 and 4 for details.

In Section 3.2, we will explain why, in general, \(v_{^{\text {bu}}}^{_{\text {in}}}<v_{^{\text {bu}}}^{_{\text {fo}}}\).

In Section 3.2, we will explain why, in general, \(c_{^{\text {se}}}^{_{\text {in}}}<c_{^{\text {se}}}^{_{\text {fo}}}\).

In Section 3.2, we will see that, in general,\(g^{_{\text {in}}}<g^{_{\text {fo}}}\).

Note the profit tax is equivalent to a value added tax on the sale of the goods.

This can capture the probability that an informal seller’s profit can be stolen or their merchandise be confiscated by government authorities, for instance.

We refer to Donovan (2008) for more on the costs of operating in the informal market.

This can take many forms such as free repair/replacement, a full money-back guarantee, on-site customer service, twenty-four hour telephone customer assistance, and/or cash compensation for unsatisfactory product performance.

Concavity is a very reasonable assumption in this context, because α is generally bounded above: \(\lim _{q{\rightarrow }{\infty }} \alpha (q)=v^{\ast }-v_{^{\text {bu}}}^{_{\text {in}}}\), where v ∗ is the value of consuming a “perfect” commodity, with no defects upon repair or replacement. Note that, given the concavity of α and the linearity of \(c_{^{\text {se}}}^{_{\text {fo} }}\) in q , there is an optimal amount of q, which may lead to a less-than-full replacement or less-than-perfect repair.

All buyers have identical preferences. If we relaxed this assumption and considered buyer heterogeneity in terms of income or preferences, then those who are poorer, less risk-averse, and/or have a higher discount rate would prefer the cheaper but less reliable goods of the informal market. Thus, buyer heterogeneity alone could explain the co-existence of the two markets. Introducing heterogeneity amongst buyers (or sellers) would only strengthen our conclusions, as there is more scope for co-existence.

We refer to Gomis-Porqueras et al. (2017) for the properties of equilibrium under price posting and auctions in environments where advertising is costly and its reach is probabilistic.

In contrast to Camera and Selcuk (2009), here prices posted by sellers cannot be renegotiated depending on market conditions, so that there is no distinction between the posted list price and the sale price

Recall that \(b^{_{\text {fo}}}\) is the ratio of buyers in the formal market relative to the total number of sellers in both markets, while \(s^{_{\text {fo}}}\) is the fraction of sellers in the formal market to the total number of sellers in both markets. Thus, we have that \(B_{f}=b^{_{\text {fo}}} /s^{_{\text {fo}}}\).

Informal buyers have some vague notion where informal sellers congregate. Once they arrive at such location, there is random search among informal sellers. We refer to Donovan (2008) for more on the characteristics of street vendors working in the underground/informal economy.

η(B i ) is a function of B i (the ratio of buyers to sellers), which will determine the relative bargaining power of a buyer and a seller. Later, in Section 4.2, we will present one possible model of this surplus division process, but there is no need to commit to a specific model here.

It would also be reasonable to assume \(\displaystyle \lim\limits_{B_{i}\searrow 0}\eta (B_{i})= 0\). But this is unnecessary for our analysis.

Formally, in a continuous-time model, where t ranges over the set of real numbers, we would define \(\dot {s}^{_{\text {fo}}} := \mathrm {d}{s}^{_{\text {fo}}}/\mathrm {d}t\) and \(\dot {s}^{_{\text {in}}} := \mathrm {d}{s}^{_{\text {in}}}/\mathrm {d}t\). In a discrete-time model, where t ranges over the set of integers, we would define \(\dot {s}^{_{\text {fo}}}(t):={s}^{_{\text {fo}}}(t + 1)-{s}^{_{\text {fo}}}(t)\) and \(\dot {s}^{_{\text {in}}}(t):={s}^{_{\text {in}} }(t + 1)-{s}^{_{\text {in}}}(t)\). Thus, the dynamical (10) admits both a continuous-time and a discrete-time interpretation. The equilibrium characterization of Theorem 3 holds in both cases.

The expected utility of buyers in the informal market is irrelevant to the dynamics of this model, because we have assumed that they cannot switch from informal to informal markets.

Typically, λ se is just multiplication by a positive constant.

That is: \(\lambda _{\text {se}}(-r)=-\lambda _{\text {se}}(r)\), for all real numbers r.

If λ se is an odd function, then the dynamical system converges to equilibrium just as quickly from either direction. Thus, the informal market would show a symmetric response to tax increases and tax decreases, as found by Christopoulos (2003) in Greece. To see how λ semight not be odd, note that it might cost more for a seller to switch from the informal market to the formal market than vice versa (e.g., because of the need to acquire licenses, rent a retail location, etc.); this would be reflected by having |λ se(r)| < |λ se(−r)| for any given r > 0. This is consistent with empirical findings by Giles et al. (2001) and (Wang et al. 2012) in Taiwan and New Zealand, respectively.

Throughout this paper, we use the term “equilibrium” to mean a stationary equilibrium —that is, one which is unchanging over time.

All sellers are ex ante identical, so they all play the same mixed strategy.

One can also imagine circumstances where it is the buyers who are mobile, while the sellers are fixed —for instance, tourists arriving at New York City who know where to find all formal and informal sellers. In that case, it would not be difficult to see that the above result (and comparative statics) would still hold.

In fact, this assumption is not critical; we could instead reverse the roles of buyers and sellers in the informal market, so that it is the informal buyers who have fixed locations (home or workplace), and informal sellers who visit them. This would correspond to the door-to-door selling strategy used by informal sellers in some developing countries. If we define \(S_{i}:={s^{_{\text {in}} }}/b^{_{\text {in}}}\) (i.e., the ratio of sellers to buyers in the informal market), then we obtain \(P_{^{\text {bu}}}^{^{\text {in}}}(S_{i} )= 1-e^{-S_{i}}\) and \(P_{^{\text {se}}}^{^{\text {in}}}(S_{i})=\frac {P_{^{\text {bu}}}^{^{\text {in}}}(S_{i})}{S_{i}}\). This alternative model yields results qualitatively identical to the results we present here.

It was not necessary to be more specific about the negotiation process in order to obtain Theorem 3.

The Nash solution selects the point in Δthat maximizes the product of the buyer’s and seller’s utilities. The egalitarian solution maximizes the minimum of the two utilities, and the Kalai-Smorodinsky solution maximizes the minimum utility after both utilities have been rescaled, ranging from 0 to 1. In the domain Δ, it is clear that the maximizers of all three trading protocols coincide with the midpoint of the diagonal line from \((g^{_{\text {in}}},0)\) to \((0,g^{_{\text {in}}})\). Indeed, this is true for any Pareto-efficient bargaining solution that respects the axiom of Symmetry.

Thus, the population of buyers and sellers in the informal market does not change over the course of a chapter.

Recall that the maximizer of the Nash trading protocols is the midpoint of the diagonal line from \((g^{_{\text {in}}},0)\) to \((0,g^{_{\text {in}}})\)

If δ = 1, then the bargaining outcome (15) can be seen as a particular case of the abstract surplus-division model considered in Section 3.3.2. To see this, let \(\eta (B_{i}):=u_{^{\text {se}} }^{_{\text {in}}}(B_{i})/g^{_{\text {in}}}\), where \(u_{^{\text {se}} }^{_{\text {in}}}(B_{i})\) is defined as in Eq. 15. Then η satisfies the conditions proposed in Section 3: it is an increasing function of B i (because \(u_{^{\text {se}}}^{_{\text {in}}}\) is a decreasing function of B i , and the limit (8) holds because \(u_{^{\text {se}}}^{_{\text {in}}}(0)=g^{_{\text {in}}}\).

Heuristically, this means we can think of \({\mathcal {B}}\) as a roughly “vertical” curve near (b ∗, s ∗), whereas \({\mathcal {S}}\) is roughly “horizontal” near (b ∗, s ∗).

Maple source code for this computation and all the computations described in the rest of this section is available on request from the authors.

We find the same qualitative results when alternative parameterizations are used.

We find the same qualitative results when alternative parameterizations are used.

We would get a similar picture for any \(L_{^{\text {bu}}}>0>L_{^{\text {se}}}\).

We find the same qualitative results when alternative parameterizations are used.

We refer to Loayza (1996) for the role of confiscation in the informal sector.

Note that, this interpretation is not conducive to view the model as a repeated game, since individual agents only live for one period, after which their offspring replace them.

References

Amaral P, Quintin E (2006) A competitive model of the informal sector. J Monet Econ 53:1541–1553

Antunes A, Cavalcanti T (2007) Start up costs, limited enforcement, and the hidden economy. Eur Econ Rev 51(1):203–224

Arnold M, Lippman S (1995) Selecting a selling institution: auctions versus sequential search. Econ Inq 33(1):1–23

Aruoba B (2010) Informal sector, government policy and institutions. In: 2010 Meeting papers of the society for economic dynamics, vol 324

Bagwell K (2007) The economic analysis of advertising. In: Armstrong M, Porter R (eds) Handbook of industrial organization, vol 28. Elsevier, Ch, pp 1701–1844

Beckert J (2005) Trust and the performative construction of markets. Max Planck Inst Study Soc 05/08:1193–1224

Burdett K, Shi S, Wright R (2001) Pricing and matching with frictions. J Polit Econ 109:1060–85

Camera G, Delacroix A (2004) Trade mechanism selection in markets with frictions. Rev Econ Dyn 7:851–868

Camera G, Selcuk C (2009) Price dispersion with directed search. J Eur Econ Assoc 7(6):1193–1224

Cason T, Friedman D, Milam G (2003) Bargaining versus posted price competition in customer markets. Int J Ind Organ 21(2):223–251

Chmielowski M (2015) Perspectives of agorism in central and eastern europe. 4Liberty.eu. Review 3:44–53

Christopoulos D (2003) Does underground economy respond symmetrically to tax changes? Evid Greece Econ Model 20:563–570

De Soto H (1989) The other path. Harper and Row, New York

D’Erasmo P, Boedo HM (2012) Financial structure, informality and development. J Monet Econ 59(3):286–302

Diamond P (1971) A model of price adjustment. J Econ Theory 3:156–168

Donovan M (2008) Informal cities and the contestation of public space: the case of bogota’s street vendors, 1988-2003. Urban Stud 1(45):29–51

Ehrman C, Peters M (1994) Sequential selling mechanisms. Econ Theory 4(2):237–53

Feige E (1990) Defining and estimating underground and informal economies: the new institutional economics approach. World Dev 18(7):989–1002

Gambetta D (1988) Mafia: the price of distrust. In: Gambetta, D (ed) Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations, pp 158–175

Giles D, Werkneh G, Johnson B (2001) Asymmetric responses of the UE to tax changes: evidence from New Zealand data. Econ Record 77(237):148

Gomis-Porqueras P, Peralta-Alva A, Waller C (2014) The shadow economy as an equilibrium outcome. J Econ Dyn Control 41(C):1–19

Gomis-Porqueras P, Julien B, Wang C (2017) Strategic advertising and directed search. Int Econ Rev 58(3):783–806

Julien B, Kennes J, King I (2002) Auctions beat posted prices in a small market. J Inst Theor Econ 158(4):548

Koreshkova T (2006) A quantitative analysis of inflation as a tax on the underground economy. J Monet Econ 53:773–796

Krishna V (2003) Asymmetric english auctions. J Econ Theory 112(2):261–288

Kultti K (1999) Equivalence of auctions and posted prices. Games Econ Behav 27(1):106–113

Lagos R, Wright R (2005) A unified framework for monetary theory and policy analysis. J Polit Econ 113:463–484

Loayza N (1996) The economics of the informal sector: a simple model and some empirical evidence from Latin America. Carn-Roch Conf Ser Public Policy 45(1):129–162

Lu X, McAfee P (1996) The evolutionary stability of auctions over bargaining. Games Econ Behav 15(2):228–254

McAfee P (1993) Mechanism design by competing sellers. Econometrica 61(6):1281–1312

Michelacci C, Suarez J (2006) Incomplete wage posting. J Polit Econ 114(6):1098–1123

Milgrom P, Weber R (1982) A theory of auctions and competitive bidding. Econometrica 50:5

Mollering G (2006) Trust: reason, routine, reflexivity. Elsevier

Nicolini J (1998) Tax evasion and the optimal inflation tax. J Dev Econ 55(1):215–232

Ordonez J (2014) Tax collection, the informal sector, and productivity. Rev Econ Dyn 17:262–286

Oviedo A, Thomas M, Karakurum-Ozdemir K (2009) Economic informality, causes, costs, and policies - a literature survey. World Bank

Peters M (1994) Equilibrium mechanisms in a decentralized market. J Econ Theory 64(2):390–423

Peters M (1995) Decentralized markets and endogenous institutions. Can J Econ 28(2):227–60

Portes A, Castells M, Benton L (1989) World underneath: the origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. In: Portes A, Castells M, Benton L (eds) The informal economy: studies in advanced and less developed countries. Johns Hopkins, Baltimore

Prado M (2011) Government policy in the formal and informal sectors. Eur Econ Rev 55(8):1120–1136

Putnins T, Sauka A (2015) Shadow economy index for the baltic states 2009-2014. 4Liberty.eu. Review 3:17–43

Rauch J (1991) Modelling the informal sector formally. J Dev Econ 35(1):33–47

Wang DH-M, Yu TH-K, Hu H-C (2012) On the asymmetric relationship between the size of the underground economy and the change in effective tax rate in Taiwan. Econ Lett 117:340–343

Acknowledgments

This paper was previously circulated under two different titles: (i) “Formal and Informal Markets: A Strategic and Dynamic Perspective” and (ii) “Formal and Informal Markets: A Strategic and Evolutionary Perspective”.

We would like to thank Nick Feltovich, Lawrence Uren and the participants of the 2012 Australasian Economic Theory Workshop and of the 2012 Australasian Public Choice Conference as well as the seminar participants at Australian National University, Deakin University, La Trobe University, Virginia Tech and anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions. Finally, we would also like to thank the anonymous referees for their input and suggestions. This work was supported by NSERC grant #262620-2008 and Labex MME-DII (ANR11-LBX-0023-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: proofs

Proof of Lemma 1

The efficient value q ∗ of investment in quality assurance is the value such thatα ′∗) = 1 (i.e., such that oneadditional cent spent on quality assurance increases the buyer’s expected utility by exactly one cent). Sinceα ′is nonincreasing (byconcavity), we have α ′(q) ≥ 1for all q ∈ [0, q ∗]. Thus, sinceα(0) = 0, the Fundamental Theoremof Calculus implies that α(q ∗) ≥ q ∗ (i.e., the benefit of quality assurance outweighs its cost). Thus,

because α(q) ≥ q. Thus, \(g^{_{\text {in}}} \leq g^{_{\text {fo}}}\). □

Proof of Theorem 3

We must show that the interval [0, 1] contains a zero for the function \({\widetilde {U}}\). By inspecting formulae (5) and (9), we see that, for all \(s^{_{\text {fo}}}\in [0,1]\), we have

Clearly, it will be sufficient to find a zero for \({\widehat {U}}\) instead. From Eq. 8, simple computations yield:

Fromhere, it is easy to check that

But \({\widehat {U}}\) is continuous on [0, 1]. Thus, if K satisfies both the conditions in Eq. 23, then the Intermediate Value Theorem implies that \({\widehat {U}}(s^{*})= 0\) for some s ∗ ∈ (0, 1). Furthermore, \({\widehat {U}}\) is going from positive values (near 0) to negative values (near 1), so \({\widehat {U}}\) must be decreasing near s ∗; hence s ∗ is a stable equilibrium.

Now, it is easy to check that the function \({\ \widehat {U}}_{2}\) is positive everywhere on [0, 1]. Thus, if K increases, then thegraph of \({\widehat {U}}\) will move downwardseverywhere. Since \({\widehat {U}}\) is decreasing near s ∗, a downward movementof the graph will cause s ∗to moveto the left in the interval [0, 1]. In other words, s ∗ will decrease when K increases. By inspection of formula (22), K is increasing with \(g^{_{\text {in}}}\) and \(T_{^{\text {se}}}^{^{\text {fo}}} \), while it isdecreasing with \(T_{^{\text {se}}}^{^{\text {in}}}\).Thus, s ∗ is decreasing with \(g^{_{\text {in}}}\) and \(T_{^{\text {se}}}^{^{\text {fo}}}\), and increasing with \(T_{^{\text {se}}}^{^{\text {in}}}\).

Meanwhile, \({\widehat {U}}_{1}\) is clearly increasing as a function of \(b^{_{\text {fo}}}\), and independent of \(b^{_{\text {in}}}\). On the other hand, \(\widehat {U}_{2}\)is independent of \(b^{_{\text {fo}}}\), but increasing as a function of \(b^{_{\text {in}}}\) (because η is an increasing function, by hypothesis). Thus, \(\widehat {U}\) is decreasing as a function of \(b^{_{\text {in}}}\) (because K is positive by inspection of formula (22)). Thus, if we increase \(b^{_{\text {fo}}} \), then the graph of \({\widehat {U}}\) will move upward (andhence, s ∗ will move to the right), whereas if we increase \(b^{_{\text {in}}}\), then the graph of \({\widehat {U}}\) will move downward (hence, s ∗ will move to the left). Thus, s ∗ is an increasing function of \(b^{_{\text {fo}}}\), and a decreasing function of \(b^{_{\text {in}}}\). □

Appendix B: replicator/imitation dynamics

Here we sketch another evolutionary framework that leads to the equilibrium represented by Eq. 11. As in the model of best response dynamics described in Section 3.4, we suppose there is an infinite sequence of time periods, with trade occurring in each market during each time period. But instead of migrating between markets in response to higher payoffs, agents learn by imitating other agents. The more agents choose a particular strategy, and the better they are doing relative to the average payoff, the more likely it is that other agents will imitate their behavior.

Alternatively, we can interpret the same model in terms of successive generations of agents. During each time period, some agents produce one or more children, and some agents die. Children remain in the same market as their parents.Footnote 53 The net reproductive rate (births minus deaths) of each market type is determined by how much the payoff for that market exceeds the population average payoff. To be precise, the population average payoff for sellers at time t is given by:

so the reproductive rate of the formal sellers will be:

The population of formal sellers will grow (or shrink) exponentially at this rate. Formally, we have \(\dot {s}^{_{\text {fo}}}(t)\ =\ \lambda _{\text {se} }\,\rho (t)\cdot s^{_{\text {fo}}}(t)\), where λ se > 0 is some constant. This leads to the following dynamical equation

where λ se > 0 is a constant. Again, this dynamical equation has both a discrete-time and a continuous-time interpretation. In either case, Eq. 11 is a necessary and sufficient condition for a population distribution \((s^{_{\text {fo}}},s^{_{\text {in}}})\) to be a “nontrivial” fixed point of the dynamics. Here, “nontrivial” refers to the fact that the replicator dynamics always have “trivial” fixed points, where \(s^{_{\text {fo}}}= 0\) or \(s^{_{\mathrm {\ in}}}= 0\). However, unless these “pure population” equilibria arise from a solution to Eq. 11, they are generally unstable to small perturbations. Thus, a pure population of this type will be destabilized as soon as even one of the reproducing agents produces a “mutant” child of the opposite type. Thus, we can safely ignore these trivial equilibria, and focus only on the equilibria described by Eq. 11.

Both buyers and sellers switching between markets

Finally, we could suppose that the buyer/seller populations both evolve according to replicator/imitation dynamics. This yields dynamical equations:

where λ se > 0 and λ bu > 0 are constants. Again, this dynamical equation has both a discrete-time and a continuous-time interpretation. In either case, Eq. 18 from Section 4.4 is a necessary and sufficient condition for a population distribution \((b^{_{\text {fo}}},b^{_{\text {in}}} ,s^{_{\text {fo}}},s^{_{\text {in}}}) \) to be a “nontrivial” fixed point of the dynamics (25). Here, “nontrivial” refers to the fact that the replicator dynamics always has “trivial” fixed points where either \(b^{_{\text {fo}}}= 0\) or \(b^{_{\text {in}}}= 0\) and either \(s^{_{\text {fo}}}= 0\) or \(s^{_{\text {in}}}= 0\).

Note that the vector field determined by Eq. 25 is obtained by multiplying the vector field defined by Eq. 16 by a scalar function that is positive everywhere in (0, b) × (0, 1). Thus, a stable fixed point for Eq. 16 is also a stable fixed point for Eq. 25.

Appendix C: alphabetical index of notation

-

α(q) Benefit (to the formal buyers) of quality assurance (e.g., warranties, free repair service, etc.)

-

\(b^{_{\text {in}}}\) Ratio of buyers in the informal market, relative to population of sellers in both markets.

-

\(b^{_{\text {fo}}}\) Ratio of buyers in the formal market, relative to population of sellers in both markets.

-

b \(=b^{_{\text {in}}}+b^{_{\text {fo}}}\). Overall ratio of buyers to sellers in the whole economy.

-

B f \(:=b^{_{\text {fo}}}/s^{_{\text {fo}}}\). Ratio of buyers to sellers in formal market.

-

B i \(:=b^{_{\text {in}}}/s^{_{\text {in}}}\). Ratio of buyers to sellers in the informal market.

-

\(c^{_{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Cost of production in the informal market.

-

\(c^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Cost of production in the formal market. (Includes quality assurance, but not taxes or regulatory compliance.)

-

δ Discount factor (in Section 4).

-

η Bargaining strength of informal sellers (in Section 3).

-

\(g^{_{\text {in}}}\) := \( v_{\text{bu}}^{\text{in}} \) − \( c_{\text{se}}^{\text{in}} \). The gains from trade in the informal market.

-

\(g^{_{\text {fo}}}\) := \( v_{\text{bu}}^{\text{fo}} \) − \( c_{\text{se}}^{\text{fo}} \). The gains from trade in the formal market.

-

\(L^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Lump sum costs for informal buyers (e.g., inconvenience).

-

\(L^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Lump sum costs for formal buyers (e.g., transportation and shoe leather costs).

-

\(L^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Lump sum costs for informal sellers (e.g., crime risk, bribery, protection money, shoe leather).

-

\(L^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Lump sum costs for formal sellers (e.g., regulatory compliance, license fees, rent).

-

\(L_{^{\text {bu}}}\) “Net” lump sum costs for formal buyers.

-

\(L_{^{\text {se}}}\) “Net” lump sum costs for formal sellers.

-

\(vP^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Match probability for informal buyers.

-

\(P^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Match probability for formal buyers.

-

\(P^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Match probability for informal sellers.

-

\(P^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Match probability for formal sellers.

-

q Expenditure on quality assurance technology by formal sellers.

-

\(R^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) \(= 1-T^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\), the residual earnings rate for informal sellers.

-

\(R^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) \(= 1-T^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\), the residual earnings rate for formal sellers.

-

\(R_{^{\text {se}}}\) \(=R^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se} }}/R^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\), the “net” residual earnings rate for formal sellers.

-

\(s^{_{\text {in}}}\) Proportion of sellers in the informal market.

-

\(s^{_{\text {fo}}}\) Proportion of sellers in the formal market.

-

t Time (in dynamical interpretation of model).

-

\(T^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Expected costs of monetary crime for informal sellers.

-

\(T^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Taxes and unit regulatory costs for formal sellers.

-

\(T_{^{\!\!ax}}\) “Net” tax burden for formal sellers.

-

\(u^{_{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Utility of a purchase for informal buyers.

-

\(u^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Utility of a purchase for formal buyers.

-

\(u^{_{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Utility of a sale for informal sellers.

-

\(u^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) Utility of a sale for formal sellers.

-

\(U^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) \(=P^{^{\text {in} }}_{^{\text {bu}}}u^{_{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\), the expected utility of informal buyers.

-

\(U^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) \(=P^{^{\text {fo} }}_{^{\text {bu}}}u^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\), the expected utility of formal buyers.

-

\(U^{^{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) = P se in u se in, the expected utility of informal sellers.

-

\(U^{^{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\) \(=P^{^{\text {fo} }}_{^{\text {se}}}u^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {se}}}\), the expected utility of formal sellers.

-

\(v^{_{\text {in}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Value of merchandise to informal buyer.

-

\(v^{_{\text {fo}}}_{^{\text {bu}}}\) Value of merchandise to formal buyer.

Appendix D: best response vector fields

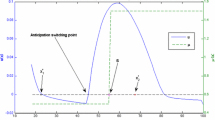

The vector fields generated by the best response differential (16), for the four cases shown in Fig. 1a. a The mixed-market equilibrium defined by the crossing of \({\mathcal {\ S}}(0,-0.5)\) and \({\mathcal {\ B}}(0.5)\) is a global attractor. b The mixed-market equilibrium defined by the crossing of \({\mathcal {\ S}}(0,0.4)\) and \({\mathcal {\ B}}(-0.4)\) is a global attractor. c The pure formal market equilibrium (0,0) is a global attractor. (D) The pure informal market equilibrium (b, s)is a global attractor

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anbarci, N., Gomis-Porqueras, P. & Pivato, M. Evolutionary stability of bargaining and price posting: implications for formal and informal activities. J Evol Econ 28, 365–397 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-017-0544-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-017-0544-2