Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We previously reported that obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome (at risk), compared with obese individuals without the metabolic syndrome (healthy obese), have elevated serum AGEs that strongly correlate with insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation. We hypothesised that a diet low in AGEs (L-AGE) would improve components of the metabolic syndrome in obese individuals, confirming high AGEs as a new risk factor for the metabolic syndrome.

Methods

A randomised 1 year trial was conducted in obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome in two parallel groups: L-AGE diet vs a regular diet, habitually high in AGEs (Reg-AGE). Participants were allocated to each group by randomisation using random permuted blocks. At baseline and at the end of the trial, we obtained anthropometric variables, blood and urine samples, and performed OGTTs and MRI measurements of visceral and subcutaneous abdominal tissue and carotid artery. Only investigators involved in laboratory determinations were blinded to dietary assignment. Effects on insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) were the primary outcome.

Results

Sixty-one individuals were randomised to a Reg-AGE diet and 77 to an L-AGE diet; the data of 49 and 51, respectively, were analysed at the study end in 2014. The L-AGE diet markedly improved insulin resistance; modestly decreased body weight; lowered AGEs, oxidative stress and inflammation; and enhanced the protective factors sirtuin 1, AGE receptor 1 and glyoxalase I. The Reg-AGE diet raised AGEs and markers of insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation. There were no effects on MRI-assessed measurements. No side effects from the intervention were identified. HOMA-IR came down from 3.1 ± 1.8 to 1.9 ± 1.3 (p < 0.001) in the L-AGE group, while it increased from 2.9 ± 1.2 to 3.6 ± 1.7 (p < 0.002) in the Reg-AGE group.

Conclusions/interpretation

L-AGE ameliorates insulin resistance in obese people with the metabolic syndrome, and may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes, without necessitating a major reduction in adiposity. Elevated serum AGEs may be used to diagnose and treat ‘at-risk’ obesity.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01363141

Funding

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK091231)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current efforts to arrest the epidemics of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, have had limited success [1–3]. Obesity is a prevalent component of type 2 diabetes, often coupled with insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in a cluster known as the metabolic syndrome, associated with chronic oxidative stress and inflammation [4–6]. Overnutrition is thought to be a major cause of obesity [5]. However, many obese people do not develop the metabolic syndrome and have been labelled ‘healthy obese’ [7–9]. Although excessive consumption of fatty foods is considered an important cause of the metabolic syndrome [4, 5], this view has recently come under new scrutiny [10, 11]. Thus, there is a need to identify alternative causes and treatments for ‘at-risk’ obese people.

Thermally prepared foods are rich in pro-inflammatory AGEs, which are also flavourful, a fact that enhances palatability and consumption and therefore may promote weight gain [12, 13]. Excessive intake of dietary AGEs has directly and causally been linked in both humans and mice to high serum AGEs, oxidative stress and inflammation, reduced innate defences, and insulin resistance [12–19]. In a cross-sectional study of obese individuals with and without the metabolic syndrome, we recently found a direct correlation between AGEs and insulin resistance. Obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome had significantly higher dietary AGE intake and serum AGEs, as well as insulin resistance, oxidative stress and inflammation, compared with healthy or obese individuals without the metabolic syndrome [20]. Two distinct serum AGE markers, carboxymethyllysine (CML) and methylglyoxal (MG) derivatives, were markedly elevated in this population and strongly correlated with elevated HOMA-IR, oxidative stress and inflammation, and decreased protective or host defence factors, such as sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and AGE receptor 1 (AGER1) [20].

Based on these observations, we hypothesised that high serum AGE levels in at-risk obese adults contribute to the risk of type 2 diabetes. We proposed that a 1 year randomised interventional trial with dietary AGE restriction (L-AGE) would improve metabolic syndrome risk factors.

Methods

Clinical protocol

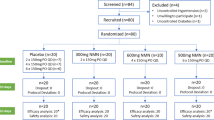

Selection criteria to participate in the study have already been published [20]. Briefly, volunteers aged 50 years or above with at least two of the following five criteria of the metabolic syndrome, based on the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (NCEP ATP III) [21], were recruited from the New York City urban community surrounding the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai: (1) waist circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women; (2) BP ≥130/85 mmHg (or use of BP-lowering medication); (3) HDL-cholesterol <1.04 mmol/l in men or <1.29 mmol/l in women; (4) triacylglycerol ≥1.69 mmol/l (or use of medication for high triacylglycerol, such as fibrates or nicotinic acid); and (5) fasting blood glucose ≥5.55 mmol/l, but an HbA1c ≤6.5%/47.5 mmol/mol, or use of metformin. Volunteers were screened with a 3 day AGE food record and those whose daily intake was ≥12 AGE equivalents per day were invited to participate in the study. These participants were then randomised either to a L-AGE diet or to their usual diet (Reg-AGE) and used as controls for the next 12 months (Fig. 1). Routine blood tests were performed in the hospital clinical laboratory. Only investigators involved in laboratory determinations were blinded to the dietary assignment. Participant recruitment started in 2011 and the trial finished in 2014.

All volunteers signed a consent form approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board. The study was registered in www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01363141).

L-AGE participants prepared their own food at home after being individually instructed on how to reduce dietary AGE intake by modifying the cooking time and temperature without changing the quantity, quality or composition of food. They were specifically instructed to avoid frying, baking or grilling, and they were encouraged to prepare their food by boiling, poaching, stewing or steaming (Table 1). It has been previously demonstrated that switching to these suggested methods of cooking limits new AGE formation in foods, especially animal food products [15]. Participants received a personal interview with the study dietitian every 3 months at the clinic to emphasise instructions and review records. In addition, a dietitian contacted them regularly via telephone (twice/week) to evaluate and promote dietary compliance. Together these measures helped avoid undue changes in calorie consumption while adhering to L-AGE.

All participants underwent a physical examination and provided a medical history at baseline. A fasting blood sample, a 24 h urine sample and previously validated 3 day food records were obtained at baseline and at 12 months (end of study). During these visits, participants also underwent an OGTT (75 g oral glucose load, followed by serum samples at 0, 60 and 120 min) and abdominal and neck MRI to define subcutaneous and visceral adipose fat distribution and carotid wall artery variables. Routine blood tests were performed in the hospital clinical laboratory. HOMA-IR was calculated from fasting blood glucose and insulin as previously published [22].

Dietary intake

Assessment of daily dietary AGE content was based on 3 day food records and estimated from a database of ∼560 foods which lists AGE values [15] expressed as AGE equivalents per day (1 AGE equivalent = 1000 kilounits). The 3 day food record is based on established guidelines developed to assist in estimating portions [15]. Nutrient intakes, important in monitoring and preventing undue changes in calorie consumption, were then estimated from food records using a nutrient software program (Food Processor, version 10.1; ESHA Research, Salem, OR, USA).

Imaging studies (MRI)

Subcutaneous and visceral abdominal fat deposits were assessed as previously described [23, 24] (electronic supplementary material [ESM] Methods).

Materials

See ESM Methods.

AGE determination

AGEs (CML and MG) in serum, urine and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PMNC) lysates were determined by well-validated, competitive ELISAs based on monoclonal antibodies for protein-bound CML (4G9) [25, 26] and protein-bound MG derivatives, i.e. arginine-MG-H1, characterised by HPLC [12], shown to detect pathologically relevant AGEs in multiple studies [12–15, 27] (ESM Methods).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from PMNCs using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). AGER1 (also known as DDOST), receptor for AGEs (RAGE, also known as AGER) and SIRT1 mRNA expression were analysed by quantitative SYBR Green real-time PCR. The transcript copy number of target genes was determined based on their Ct values [17, 20, 27] (ESM Methods).

Ex vivo studies

Cell culture

PMNCs from individuals with the metabolic syndrome were separated from fasting, EDTA anticoagulated blood by Ficoll-Hypaque Plus gradient (GE Healthcare Bioscience, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and incubated in serum-free culture media AIM-V (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 h, followed by the addition of MG-BSA (60 μg/ml) [12, 14, 16]. MG-BSA contained 22 MG-modified arginine residues per mole based on HPLC. MG-BSA was passed through an endotoxin-binding affinity column (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) to remove endotoxins [12, 14] (ESM Methods). Cells were incubated with or without the SIRT1 inhibitor Sirtinol (10 μmol/l; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) or a SIRT1 activator, SRT1720 (1 μmol/l; Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA). After 72 h, the cells were harvested for western blotting, the culture medium was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min and the supernatant fraction was collected for testing human TNFα levels with an ELISA kit (Invitrogen) [28]. In a separate study, PMNCs from normal volunteers without the metabolic syndrome, described previously [20], were used as controls for PMNCs from individuals with the metabolic syndrome. All baseline cellular data were collected from PMNCs obtained at study commencement.

Conditioned medium

PMNCs freshly isolated at baseline and at study end were plated in serum-free culture media at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. The media were collected and centrifuged to remove cells and other particles and concentrated by Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Sigma-Aldrich) for co-culture experiments [14].

Adipocyte culture and treatment

3T3-L1 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), cultured and differentiated, as described [12], were incubated with DMEM or PMNC conditioned medium diluted at 1:500 with DMEM for 18–24 h. After washing and replacing media with Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution for 1 h, cells were stimulated with insulin (100 nmol/l) for 30 min before they were harvested.

Western blotting

After incubating PMNCs with MG-BSA and with or without Sirtinol or SRT1720 for 72 h, cells were disrupted in lysis buffer. The cellular proteins were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred on to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. To test for NFkB acetylation, 250 μg protein lysate was immunoprecipitated by an anti-NFkB p65 antibody at 4°C overnight. Protein A/G agarose beads 60 μl were added. The immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with a specific anti-acetyl-NFkB p65 (lysine 310) antibody, 3T3-L1 adipocyte lysates (50 μg) were immunoblotted by anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) antibody or immunoprecipitated (400 μg) by anti-insulin receptor-β antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Of the 383 individuals originally screened for eligibility, 138 were randomised (Fig. 1). Participants were considered eligible for analysis if they attended at least the 6 month clinic appointment. The pre-specified statistical analysis plan defined the study outcomes to be the mean differences between the final recorded values minus the baseline values for the Reg-AGE and L-AGE groups. The primary outcome variable was taken to be HOMA-IR. Sample size was established on the basis of prior studies showing an effect of L-AGE on healthy individuals who had a difference in HOMA-IR between those on L-AGE and those on normal diets of 4.57 [17]. To find a difference of 4 with 80% power would require a sample size of 98. Allowing for ∼20% dropout, a sample size of 120 was proposed (60 in each group, to maximise power). Due to a higher per cent dropout in the L-AGE group, the total recruitment was increased to 138 (Fig. 1).

The study statistician performed the randomisation and all statistical analyses (Stata software, version 12; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive analyses summarised continuous variables at baseline through their mean (SD) and median (first quartile, third quartile). Categorical variables were summarised using percentages. On the whole, the outcome variables (the differences between the mean within-intervention group differences over the length of the trial) were not greatly skewed. Thus, although the primary analyses were from t tests, sensitivity analyses were conducted using both general linear models, to adjust for sex, race, BMI and baseline age, and non-parametric Wilcoxon tests in case of skewed variables.

Results

Human data

General description

Baseline characteristics of cohorts randomised to L-AGE and Reg-AGE who finished the study (Fig. 1) are shown in Table 2. Both groups included participants who had two or more features of the metabolic syndrome and displayed no baseline differences in any variables, except for BMI, serum vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) and glyoxalase I. We have previously compared this population with a cohort of age- and sex-matched volunteers without the metabolic syndrome [20].

Interventional data

AGE restriction markedly improves insulin resistance and modestly reduces body weight

The effects of the intervention on the different variables are depicted in Table 3 and ESM Table 1. The L-AGE compared with the Reg-AGE diet led to a marked decrease in HOMA, fasting plasma insulin and insulin levels at 120 min of an OGTT (Fig. 2a, b ). There were no end-of-study effects on fasting blood glucose, HbA1c levels or blood glucose at 60 and 120 min of the OGTT. However, HOMA decreased in 80% of participants on the L-AGE diet compared with 31% on the Reg-AGE diet.

Effects of L-AGE diet (black bars) vs Reg-AGE diet (white bars) on metabolic variables and systemic markers of AGEs, oxidative stress and inflammation (also see Table 2). (a) Markers of insulin resistance: per cent changes (means ± SEM) in levels of HOMA, leptin and fasting insulin between baseline and end of study (Reg-AGE, n = 43; L-AGE, n = 51; *p ≤ 0.05). (b) Plasma insulin after OGTT: per cent changes (means ± SEM) in plasma insulin levels 0 and 120 min after OGTT between baseline and end of study (Reg-AGE, n = 43; L-AGE, n = 51; *p ≤ 0.05). (c) AGEs and pro-oxidative stress and inflammation markers: per cent changes (means ± SEM) in markers of serum (s) AGEs (CML, MG), plasma 8-isoprostanes (8-iso) and PMNC inflammatory factors (TNFα protein and RAGE mRNA) between baseline and end of study (Reg-AGE, n = 33; L-AGE, n = 21; *p ≤ 0.05). (d) Anti-oxidative stress and inflammation markers: per cent changes (means ± SEM) in levels of antioxidants and markers of host defence, SIRT1, AGER1 and GLO1 mRNA, between baseline and end of study (Reg-AGE, n = 33; L-AGE, n = 21; *p ≤ 0.05)

Both diets were associated with a modest weight loss, which reached significance only in the L-AGE group (Table 3; ESM Table 1). Of note, markers of insulin resistance (HOMA and fasting plasma insulin), as well as serum AGEs and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, including 8-isoprostanes, RAGE and TNFα, were reduced even in those participants on the L-AGE diet who did not lose body weight (n = 12). By comparison, there were no such end-of-study changes in participants on the Reg-AGE diet who lost weight (n = 25) (ESM Table 2).

We observed no end-of-study effects on abdominal visceral and subcutaneous fat deposits or on carotid wall variables by MRI, and there was no effect on BP, plasma triacylglycerols or HDL (Table 3; ESM Table 1).

The effect of the L-AGE diet on HOMA-IR remained highly significant, after adjusting for baseline BMI and intake of calories, protein, carbohydrate and fat, as well as age, sex and race.

Dietary AGE restriction improves inflammatory and host defence markers

There were marked decreases in circulating AGE markers (serum CML and MG) (Fig. 2c), as well as in intracellular AGEs (iCML and iMG) of PMNCs and in urinary AGEs (CML and MG) in the L-AGE group (Table 2 ). By contrast, in the Reg-AGE cohort, serum AGEs, intracellular AGEs and urinary AGEs continued to increase (Table 2; Fig. 2c).

Levels of 8-isoprostanes, as well as TNFα, VCAM1 and RAGE, were decreased in the L-AGE cohort at the end of the study (Table 2; Fig. 2c, d). On the other hand, the levels of anti-oxidative stress and inflammatory SIRT1, AGER1, adiponectin and glyoxalase I were increased in this group at the end of the study. By comparison, and similar to earlier studies [17, 19], in the Reg-AGE group, 8-isoprostanes, RAGE, HOMA-IR and leptin levels continued to increase (Table 3; Fig. 2a). There were no differences in lipid levels or renal function before and after the study in either group (Table 3).

Sex, race, ethnicity and AGEs

None of the above effects of the L-AGE diet were modified after adjusting for sex, age, race or ethnicity. There were no significant side effects reported by either group during the intervention, although more participants in the L-AGE group were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1).

Ex vivo data: L-AGE intervention reverses host deficiency of PMNCs, improving dysmetabolic effects on adipocytes

PMNCs from metabolic syndrome volunteers were compared with PMNCs from healthy individuals, as previously described [20]. Cells from those with the metabolic syndrome had lower SIRT1 and AGER1 and increased TNFα protein levels, consistent with a pro-inflammatory metabolic syndrome PMNC phenotype [20], compared with PMNCs from participants without the metabolic syndrome (Fig. 3a, b).

Baseline ex vivo cellular data: AGEs suppress host defences and promote inflammatory activation of PMNCs in individuals with the metabolic syndrome (MS) compared with normal individuals (NL). (a) Expression levels of anti-oxidative stress and inflammation factors, SIRT1 (white bars) and AGER1 (black bars), and (b) of the pro-oxidative stress and inflammation cytokine TNFα protein in PMNCs freshly obtained at study commencement (baseline), from obese study MS participants (MS-PMNCs) (black bar) compared with that in PMNCs simultaneously obtained from NL (white bar). Data in (a) are from western blots and densitometry, shown as AU or ratio of target protein to β-actin (means ± SEM) and in (b) as (means ± SEM) pg/mg cell protein by ELISA (n = 10/group, each in triplicate; *p ≤ 0.05 vs NL). (c) Baseline MS-PMNCs were exposed ex vivo to MG-BSA 60 μg/ml for 72 h, in the presence or absence of a SIRT1 activator, SRT1720 (1 μmol/l), or a SIRT1 inhibitor, sirtinol (10 μmol/l). Western blots, performed on cell extracts, and density analysis (means ± SEM) (n = 3–5) are shown as the ratio of SIRT1 (white bars) or AGER1 (black bars) to β-actin; *p ≤ 0.05 vs non-stimulated MS-PMNCs (control, CL); † p ≤ 0.05 vs MG alone. (d) MS-PMNC extracts, prepared as in (c), were also probed for levels of p-JNK (black bars) and acetylated NFkB p65 at lys310 (Acl-p65) (white bars) by western blots, using the respective antibodies and density analyses. Total JNK and p65 served as internal controls (CL). Density data (means ± SEM, n = 3–5) indicate the ratios of phosphorylated or acetylated protein to total protein; *p ≤ 0.05 vs non-stimulated CL; † p ≤ 0.05 vs MG alone. (e) TNFα secreted into the culture medium at 72 h from non-stimulated MS-PMNCs (CL, white bar) or MG-stimulated MS-PMNCs (black bars) at baseline, in the presence or absence of SRT1720 (1 μmol/l) or sirtinol (10 μmol/l), as above. Assays were performed in triplicate for each sample. Data (means ± SEM) are shown as per cent of control (n = 7, *p ≤ 0.05 vs CL; † p ≤ 0.05 vs MG alone). All PMNC samples were collected at study baseline

Ex vivo stimulation of baseline PMNCs with MG-BSA suppressed SIRT1 and AGER1 protein levels (Fig. 3c) and increased inflammatory markers (via JNK phosphorylation), marked by increased TNFα secretion (Fig. 3d, e). These responses were modulated by a SIRT1 agonist and a SIRT1 inhibitor (Fig. 3a–c), directly implicating SIRT1 in these events [29].

At study end, PMNCs from L-AGE, but not Reg-AGE, participants, displayed lower TNFα secretion (Fig. 4a; ESM Table 1). Moreover, when insulin-stimulated 3T3-L1 adipocytes were exposed to the L-AGE conditioned medium from PMNCs obtained at study end, they revealed an improved Akt and insulin receptor phosphorylation pattern compared with adipocytes exposed to Reg-AGE conditioned medium (Fig. 4b, c).

End-of-study ex vivo cellular data: L-AGE diet mitigates inflammatory activation of PMNCs from individuals with the metabolic syndrome (MS-PMNCs) and improves their impact on insulin responses of adipocytes in vitro. (a) TNFα from MS-PMNCs secreted into the conditioned media , after 1 year on L-AGE (black bar, n = 5) or Reg-AGE diet (white bar, n = 5). Data are shown as means ± SEM pg/ml medium, each in triplicate; *p ≤ 0.05 L-AGE vs Reg-AGE diet. (b) JNK phosphorylation in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes after overnight incubation with conditioned medium either from baseline (BL) or end-of-study PMNCs from L-AGE (black bar, n = 5) and Reg-AGE (white bar, n = 5) treatment groups. Cell lysates were subjected to western blot and densitometry. As additional control, 3T3-L1 adipocytes were incubated with normal culture medium, shown as 0. Density data are means ± SEM (n = 3–5 independent experiments); *p ≤ 0.05, L-AGE or Reg-AGE vs BL; † p ≤ 0.05, L-AGE vs Reg-AGE diet. (c) Serine phosphorylation (at Ser473) of Akt and tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor (IR) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes after exposure to conditioned medium (CM) overnight as in (b). Cells were incubated in the presence (black bars) or absence of insulin (Ins) (white bars) (100 nmol/l, 30 min) and subjected to western blot and densitometry (means ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments); *p ≤ 0.05 L-AGE vs BL. PMNC samples (n = 7) were from the same individuals evaluated at baseline (Fig. 2, n = 7). 3T3-L1 adipocytes incubated with normal CM are shown as 0

Discussion

This 1 year intervention shows that L-AGE diet can improve insulin resistance, a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes, in obese people with the metabolic syndrome. It also provides clinical evidence that elevated levels of AGEs, related to AGE-rich diets, are a causal factor of insulin resistance. Since maintaining weight reduction is a difficult objective, finding that L-AGE mitigates insulin resistance in at-risk obese people introduces a novel additional approach (e.g. to calorie restriction or drugs) in the treatment of insulin resistance, and, thus, prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes. Since this was possible without a modification in energy intake, or substantial weight reduction, L-AGE may offer a feasible treatment goal of risk reduction in obese people.

We recently reported that obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome consume significantly greater amounts of dietary AGEs compared with healthy obese individuals even when consuming similar amounts of calories [20]. Herein, after 1 year of L-AGE, insulin resistance markers including HOMA and plasma insulin (fasting and 2 h OGTT) as well as leptin markedly decreased to near-normal levels [20]. There was also a modest weight loss in the L-AGE group, the impact of which on insulin resistance is uncertain. However, insulin resistance changes were independent of BMI, as well as of total calorie and nutrient consumption. Furthermore, insulin resistance markers (HOMA, fasting plasma insulin and leptin) improved even in those on the L-AGE diet who did not have any change in body weight. Moreover, those on the Reg-AGE diet who lost body weight were found at study end to have increased levels of markers of insulin resistance or of oxidative stress and inflammation (ESM Table 2 ). Together these findings are consistent with the view that insulin resistance is partly independent of adiposity.

In the absence of overt diabetes or renal failure, dietary AGE consumption is shown to promote high serum AGE levels, which can influence insulin sensitivity [17–19]; thus, dietary AGEs are a risk factor for insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome, distinct from overnutrition. Diets rich in flavourful AGEs [13] may promote food consumption and can lead to obesity [20].

The marked reductions in serum and PMNC (intracellular) AGEs, due to the L-AGE diet, together with reduced TNFα as well as RAGE levels, in this non-diabetic cohort with the metabolic syndrome (normal HbA1c and fasting blood glucose) confirm the view that dietary AGEs can foment dysmetabolism via oxidative stress and inflammation [20, 29]. Indeed in the L-AGE group oxidative stress and inflammation decreased in tandem with insulin resistance, thus delaying progression to type 2 diabetes. By comparison, worsening insulin resistance and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in the Reg-AGE group, also noted in shorter trials [17], were possibly due to an expanding net AGE pool from both exogenous and endogenous sources. Thus, this 1 year trial temporally documents increased risk of progression to type 2 diabetes linked to an AGE-rich diet.

The L-AGE diet benefited several defensive factors which were found to be suppressed at baseline [20], including SIRT1, a master regulator of inflammation, insulin action, fat mobilisation [7, 30, 31] and cognitive function [32]; AGER1, an AGE receptor that antagonises AGEs, oxidative stress and inflammation [33]; and the anti-inflammatory adiponectin [34]. Restored SIRT1 and AGER1 have been implicated in the benefits of L-AGE on the metabolic syndrome as well as on dementia or Alzheimer’s disease in mice [14, 24, 35]. L-AGE increased mRNA levels of GLO1, encoding glyoxalase I, an MG-degrading enzyme (thus a protective factor) [36], which is an altogether new and novel finding. Taken together, levels of seven genes important in the balance of oxidative stress and inflammation were largely restored to normal by the L-AGE diet at the end of the study. Greater bioavailability of native antioxidants under the L-AGE diet might also have contributed to those effects.

The effects of L-AGE on PMNCs were likely reflected in peripheral tissues, although we did not directly assess adipose tissue [14, 27]. At study end, PMNCs from L-AGE individuals secreted less TNFα, such that PMNCs no longer impaired adipocyte responses to insulin. Indeed, PMNCs, like macrophages, participate in adipocyte dysfunction [28, 36], and chronic dietary AGE excess by inciting PMNC activation can impair adipocyte insulin sensitivity [12]. The pro-inflammatory phenotype of PMNCs was reversed at study end by the L-AGE diet, strongly concurring at the cellular level with the systemic findings. The net effect of L-AGE on the balance of oxidative stress and inflammation involved a robust improvement in insulin resistance.

The absence of changes at study end on central fat or carotid wall area by MRI in either group may be partly because there were no detectable abnormalities at baseline. Similarly, there were no effects on BP, plasma HDL or triacylglycerols, possibly due to the concurrent use of BP- and lipid-lowering drugs. We did not find that age, race, ethnicity and sex had an effect on the efficacy of the intervention.

AGEs may be estimated by immunochemical (ELISA) [25, 26, 37], chromatographic and mass-spectroscopy methods [18, 38]. Herein, AGEs were assessed by ELISA, a standard method used extensively to demonstrate their role in chronic disease as well as the benefits of AGE modulation in restoring health [12–15, 17–20, 25–27, 29, 33].

Weaknesses of this trial include the relatively small cohort size and the use of HOMA-IR instead of direct assessment methods of insulin resistance and sensitivity [39]. This 1 year L-AGE trial did not directly demonstrate an effect on the rate of progression to overt type 2 diabetes; however, insulin resistance, and thus risk of type 2 diabetes, decreased in the majority (80%) of L-AGE participants, compared with only 31% in the Reg-AGE group. More withdrawals in the L-AGE group might have resulted from dietary behavioural changes requiring significant effort and time commitment only in this subgroup.

In conclusion, L-AGE is effective against insulin resistance in obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome. Longer trials employing L-AGE alone or combined with other interventions should determine efficacy on risk of cardiovascular disease and other features of the metabolic syndrome.

Abbreviations

- AGER1:

-

AGE receptor 1

- CML:

-

Carboxymethyllysine

- L-AGE:

-

Restricted AGE intake

- MG:

-

Methylglyoxal

- PMNC:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for AGEs

- Reg-AGE:

-

Regular AGE intake

- SIRT1:

-

Sirtuin 1

- VCAM1:

-

Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

References

Amos AF, McCarty DJ, Zimmet P (1997) The rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010. Diabet Med 14(Suppl 5):S1–S85

Fox CS, Pencina MJ, Meigs JB, Vasan RS, Levitzky YS, D’Agostino RB Sr (2006) Trends in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus from the 1970s to the 1990s: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 113:2914–2918

Jason J, Laedtke T, Parisis JE, O’Brien P, Petersen RC, Butler PC (2004) Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53:474–481

Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH (2004) Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 27:2444–2449

Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J (2008) Dietary intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation 117:754–761

Hotamisligil GS (2006) Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444:860–867

Roberson LL, Aneni EC, Maziak W et al (2014) Beyond BMI: the ‘metabolically healthy obese’ phenotype, its association with clinical/subclinical cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality—a systematic review. BMC Public Health 14:14

Stefan N, Haring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB (2013) Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 1:152–162

Hankinson AL, Daviglus ML, Van Horn L et al (2013) Diet composition and activity level of at risk and metabolically healthy obese American adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21:637–643

Mozzafarian D, Ludwig D (2015) The 2015 US dietary guidelines: lifting the ban on total dietary fat. JAMA 313:2421–2422

Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S et al (2014) Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 160:398–406

Cai W, Gao QD, Zhu L, Peppa M, He C, Vlassara H (2002) Oxidative stress-inducing carbonyl compounds from common foods: novel mediators of cellular dysfunction. Mol Med 8:337–346

Vlassara H, Striker GE (2011) AGE restriction in diabetes mellitus: a paradigm shift. Nat Rev Endocrinol 7:526–539

Cai W, Ramdas M, Zhu L, Chen X, Striker GE, Vlassara H (2012) Oral advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) promote insulin resistance and diabetes by depleting the antioxidant defenses AGE receptor-1 and sirtuin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:15888–15893

Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S et al (2010) Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc 110:911–916

Birlouez-Aragon I, Saavedra G, Tessier FJ et al (2010) A diet based on high-heat-treated foods promotes risk factors for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 91:1220–1226

Uribarri J, Cai W, Ramdas M et al (2011) Restriction of advanced glycation end products improves insulin resistance in human type 2 diabetes: potential role of AGER1 and SIRT1. Diabetes Care 34:1610–1616

Mark AB, Poulsen MW, Andersen S et al (2014) Consumption of a diet low in advanced glycation end products for 4 weeks improves insulin sensitivity in overweight women. Diabetes Care 37:88–95

Vlassara H, Cai W, Goodman S et al (2009) Protection against loss of innate defenses in adulthood by low advanced glycation end products (AGE) intake: role of the antiinflammatory AGE receptor-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:4483–4491

Uribarri J, Cai W, Woodward M et al (2015) Elevated serum advanced glycation endproducts in obese indicate risk for the metabolic syndrome: a link between healthy and unhealthy obese? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100:1957–1966

NCEP (2002) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106:3143-3421

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS et al (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Bonekamp S, Ghosh P, Crawford S et al (2008) Quantitative comparison and evaluation of software packages for assessment of abdominal adipose tissue distribution by magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Obes (Lond) 32:100–111

Fayad ZA, Mani V, Woodward M et al (2011) Safety and efficacy of dalcetrapib on atherosclerotic disease using novel non-invasive multimodality imaging (dal-PLAQUE): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 378:1547–1559

Makita Z, Vlassara H, Cerami A, Bucala R (1992) Immunochemical detection of advanced glycosylation end products in vivo. J Biol Chem 267:5133–5138

Mitsuhashi T, Vlassara H, Founds HW, Li YM (1997) Standardizing the immunological measurement of advanced glycation endproducts using normal human serum. J Immunol Methods 207:79–88

Cai W, Uribarri J, Zhu L et al (2014) Oral glycotoxins are a modifiable cause of dementia and the metabolic syndrome in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4940–4945

Yoshizaki T, Schenk S, Imamura T et al (2010) SIRT 1 inhibits inflammatory pathways in macrophages and modulates insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298:E419–E428

Uribarri J, Cai W, Pyzik R et al (2014) Suppression of native defense mechanisms, SIRT1 and PPARγ, by dietary glycoxidants precedes disease in adult humans; relevance to lifestyle-engendered chronic diseases. Amino Acids 46:301–309

Liang F, Kume S, Koya D (2009) SIRT1 and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5:367–373

Yoshizaki T, Milne JC, Imamura T et al (2009) SIRT1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol 29:1363–1374

Guarente L (2011) Franklin H. Epstein lecture. Sirtuins, aging, and medicine. N Engl J Med 364:2235–2244

Torreggiani M, Liu H, Wu J et al (2009) Advanced glycation end product receptor-1 transgenic mice are resistant to inflammation, oxidative stress, and post-injury intimal hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 175:1722–1732

Takemura Y, Ouchi N, Shibata R et al (2007) Adiponectin modulates inflammatory reactions via calreticulin receptor-dependent clearance of early apoptotic bodies. J Clin Invest 117:375–386

de Kreutzenberg SV, Ceolotto G, Papparella I et al (2010) Downregulation of the longevity-associated protein sirtuin 1 in insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome: potential biochemical mechanisms. Diabetes 59:1006–1015

Brouwers O, Niessen PM, Ferreira I et al (2011) Overexpression of glyoxalase-I reduces hyperglycemia-induced levels of advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in diabetic rats. J Biol Chem 286:1374–1380

Bucala R, Makita Z, Koschinsky T et al (1993) Lipid advanced glycosylation: pathway for lipid oxidation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:6634–6638

Scheijen JL, Clevers E, Engelen L et al (2016) Analysis of advanced glycation endproducts in selected food items by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: presentation of a dietary AGE database. Food Chem 190:1145–1150

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant DK091231 to HV) and by the National Institute of Research Resources (grant MO1-RR-00071 to the General Clinical Research Center at Mount Sinai School of Medicine) for clinical and statistical support.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

HV designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. WC participated in the experimental design, the acquisition and interpretation of data, and reviewed the manuscript. ET, the study dietitian, participated in the design of the dietary protocol and the interpretation of nutritional data, and reviewed the manuscript. RP, the study coordinator, participated in the design of the clinical protocol and the acquisition and interpretation of clinical data, and reviewed the manuscript. KY, the study coordinator, participated in the design of the clinical protocol and the acquisition of clinical data, and reviewed manuscript. LG, the study dietitian, participated in the design of the dietary protocol and the acquisition of nutritional data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. LT, a study dietitian, participated in the design of the dietary protocol and the acquisition and interpretation of nutritional data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. XC participated in the experimental design and the acquisition of data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. VM participated in the study design and performance and in the interpretation of data from MRI studies, and edited the final manuscript. ZAF participated in the original study design and performance and in the interpretation of data from MRI studies, and edited the final manuscript. GN participated in the study design and in all the statistical analyses, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. GES participated in the study design and interpretation of data, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. JCH participated in the study design and interpretation of data and reviewed the final manuscript. JU participated in the design of the study, the acquisition and interpretation of data and in the statistical analyses, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. JU and HV are the guarantors of this work. All authors have revised the final updated version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM

(PDF 249 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vlassara, H., Cai, W., Tripp, E. et al. Oral AGE restriction ameliorates insulin resistance in obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 59, 2181–2192 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4053-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-016-4053-x