Abstract

We estimate standard production functions with a new cross-country data set on business sector production, wages and R&D investment for a selection of 14 OECD countries including the US. The data sample covers years the 1960–2004. The data suggest that growth differences can largely be explained by capital deepening and the ability to produce new technology in the form of new patents. We also find strong evidence of complementarity between patents and openness of the economy, but little evidence of increasing elasticity of substitution over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Privatization and redefinitions of the public sector can also affect the measures of the business sector, but we believe this measure is still less akin to measurement problems.

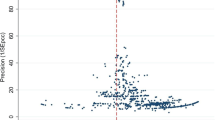

We estimated a conventional convergence equation in terms of the US (with the data from 13 countries) where the relative output growth was explained by lagged (log) level of relative output (expressed in Euros) and time dummies (fixed time effects). The estimate of the lagged output level was −0.0021, with a t-ratio of 2.24. The result is consistent with the convergence property although the effect is not particularly strong. For a more thorough analysis of convergence, see e.g., Caselli et al. (1996).

As pointed out in the introduction, the data are related to the business sector only, covering the period 1960–2004. The data are annual. Output data have not been available for Greece. Most of the data are from the OECD database (including the STAN database for the R&D expenditures). The data are described in detail in Pyyhtiä (2007).

Unfortunately, we have comparable data on R&D expenditures only for the period 1981–2004, so we cannot adequately control for R&D for the full sample period. Thus, we can only test the hypothesis that R&D has been particularly important in the last two decades.

Due to autocorrelation, the t-values do not follow the t-distribution.

Klump and Preissler (2000) discuss a relationship between elasticity of substitution of the economy and the overall flexibility of production and markets, readiness to make structural and institutional changes and so on. Elasticity of substitution between factors of production is itself a reasonably good indicator of overall structural flexibility of the economy.

Willman (2002) points out that after increasing strongly in the 1970s, the share of labour income in GDP in the euro area decreased continuously in the two subsequent decades. This suggests that a Cobb-Douglas production function might not be an appropriate choice for production analysis. Furthermore, Duffy and Papageorgiou (2000) report relatively large differences in factor shares across the countries.

For the latter half of the sample, the coefficient of k/l was not significant. When estimating the VES production function we seem, in general, to have problems in identifying the effect of technical change and the effect of changing elasticity of substitution. This is because the capital-output ratios show an upward trend in all countries included in our sample. Consequently, various combinations of technical change and substitution parameters produce almost identical error variance.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P (1998) Endogenous Growth Theory. MIT Press, Cambridge

Aghion P, Howitt P (2005) Appropriate growth policy: a unifying framework. Joseph Schumpeter Lecture, EEA, Amsterdam

Antras P (2004) Is the US Aggregate production function Cobb-Douglas? New estimates of the elasticity of substitution. Contrib Macroecon 4:1–33

Arrow K, Chenery H, Minhas B, Solow R (1961) Capital-labour substitution and economic efficiency. Rev Econ Stat 43:225–250

Caselli F, Esquivel G, Lefort F (1996) Reopening the convergence debate: new look at cross-country growth empirics. J Econ Growth 1:363–389

Chirinko RS (2008) σ: the long and short of it. J Macroecon 30:671–682

Coe D, Helpman E (1995) International R&D spillovers. Eur Econ Rev 39(5):859–887

Dernis H Khan M (2004) Triadic patent family methodology. OECD STI Working Paper DSTI/DOC/2004/2

Duffy J, Papageorgiou C (2000) A cross-country empirical investigation of the aggregate production function specification. J Econ Growth 5:87–120

Easterly W (2001) The lost decades: explaining developing countries’ stagnation in spite of policy reform 1980–1998. J Econ Growth 6:135–157

Gollin D (2002) Getting income shares right. J Polit Econ 110(2):458–474

Grossman G, Helpman E (1991) Quality ladders in the theory of growth. Rev Econ Stud 58(1):43–61

Jones C (2003) Growth, capital shares, and a new perspective on production functions. Unpublished, U.C. Berkeley

Jones C (2005) The shape of production functions and the direction of technical change. Quart J Econ 120(2):517–549

Jones C, Williams J (1997) Measuring the social return to R&D. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC

Karagiannis G, Palivos T, Papageorgiou C (2004) Variable elasticity of substitution and income growth: theory and evidence. Unpublished mimeo

Klump R, De La Granville O (2000) Economic growth and the elasticity of substitution: two theorems and some suggestions. Am Econ Rev 90:282–291

Klump R, Preissler H (2000) CES production functions and economic growth. Scand J Econ 102:41–56

Knight M, Loayza N, Villanueva D (1993) Testing the neoclassical theory of economic growth, a panel data approach. Staff Pap Int Monet Fund 40:512–541

Miyagiwa K, Papageogiou C (2007) Endogenous aggregate elasticity of substitution. J Econ Dyn Control 31:2899–2919

Nadir MI (1993) Innovations and technological spillovers. Working Paper No. 4423, NBER

Pyyhtiä I (2007) Why is Europe lagging behind? Bank of Finland Discussion Paper 3/2007

Revankar N (1971) A class of variable elasticity of substitution production functions. Econometrica 29:61–71

Saam M (2004) Distributional effects of growth and the elasticity of substitution. University of Frankfurt. Unpublished

Saam M (2008) Openness to trade as a determinant of the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour. J Macroecon 30:691–702

Steil B, Victor D, Nelson R (eds) (2002) Technological innovation & economic performance. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Willman A (2002) Euro area production function and potential output: a supply side system approach. European central bank, Working Paper No. 153

Yuhn K (1991) Economic growth, technical change biases, and the elasticity of substitution: a test of the De La Grandville hypothesis. Rev Econ Stat 73(2):340–346

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jouko Vilmunen and two anonymous referees for many useful comments and Tarja Yrjölä for helping us with the data. Viren also thanks the OP Bank Group Research Foundation and the Turku PCRC for financial support. The views are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kilponen, J., Viren, M. Why do growth rates differ? Evidence from cross-country data on private sector production. Empirica 37, 311–328 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9110-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9110-y